40 years after its approval, the Spanish Religious Freedom law faces various challenges, but “it is not a political priority”, evangelical leaders point out.

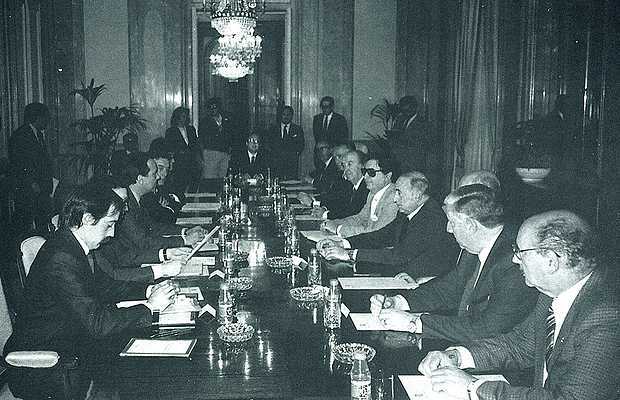

King Juan Carlos I during the first opening session of the Spanish Parliament in 1979, where the Organic Law of Religious Freedom was approved one year later. / Spanish Parliament archive.

King Juan Carlos I during the first opening session of the Spanish Parliament in 1979, where the Organic Law of Religious Freedom was approved one year later. / Spanish Parliament archive.

On June 24, 1980, the Spanish Parliament approved the Organic Law of Religious Freedom with 294 votes in favor, five abstentions and no vote against.

The text of the law was published on 5 July in the Official State Gazette, with a first paragraph assuring that “the state guarantees the fundamental right to freedom of religion and worship”, that "religious beliefs shall not constitute a reason for inequality or discrimination before the law” and that "no religion shall be the state religion”.

“What many people ignore is that there were two laws of religious freedom”, Juan Antonio Monroy, a historical figure of Spanish Protestantism who participated in the talks with the State between the last years of the dictatorship until the drafting of the Cooperation Agreements in 1992.

“The difference between 1967 and 1980 was that the first was drawn up by the government while there was consensus on the second”, he underlined speaking to Spanish news website Protestante Digital

Monroy highlighs the figure of Eduardo de Zulueta, in charge of the Religious Affairs Office until 1979, who “brought together at the Ministry of Justice representatives of the Evangelicals, Jews, Muslims, Jehovah's Witnesses, Buddhists, Orthodox, Mormons, Baha'is, Anglicans and a representative of the Catholic Church. He listened to everyone and took their opinions into account when putting his team to work”.

40 years after its approval, the text faces different challenges, also related to the contextual gap. However, “this issue is not a political priority”, says the General Secretary of the Federation of Evangelical Religious Entities of Spain (FEREDE), Mariano Blázquez, “Today there is no political consensus similar to that of the past. There is a certain fear of modifications”.

According to Xesús Manuel Suárez, Secretary General of the Spanish Evangelical Alliance (AEE), the main impediment to implementing religious freedom in Spain has been that “the collective mentality has not severed its Trento roots, its intolerance, its imposition of a single way of thinking, its limitations in managing differences and its desire to persecute those who are different”.

“Spain, five centuries after [the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation] continues to be dogmatic and Tridentine, whether the right or the left governs, and does not know how to get out of national Catholicism without falling into a dogmatizing secularism”, Suárez laments.

Blázquez stresses that “the organic laws are designed for the development of fundamental rights and public freedoms. What is expected of these rules is that they reflect a consensus within the parties on rights and structural issues of the state”.

All of this, in the midst of a society where the number of people who identify as atheists has doubled since 2010. Then, they were 7.2% of the population, now in 2020 they are 14.8%, according to official figures.

“Spain has not understood Protestantism and therefore does not understand laicism correctly. It was the Protestant worldview that established the separation between Church and State, which in no way excludes faith from public life. Spanish secularism is more a heir to the Catholic Tridentism than to the Protestant system of freedoms”, Suárez points out.

There are not many voices within the Spanish Protestantism that question the value that the law had at the time. With the law, “we have prospered”, says Monroy from a historical perspective.

However, today it is difficult to find any of those same voices that do not support a revision of the law. “The law can be improved and needs to be updated to the current reality", Blázquez states.

“The Organic Law of Religious Freedom needs legal and regulatory development, in order to clarify some issues and provide content and limits to the rights and obligations of this law. Then, we will be able to appreciate its true potential, which goes beyond being a declaration or a mere decorative instrument in the current legal framework”, the Secretary General of FEREDE underlines.

[photo_footer] The signing of the Cooperation Agreements between the representatives of the State and FEREDE in 1992. [/photo_footer]

For Blázquez, the updating of the regulations should be carried out “through ordinary and lower-ranking laws that are approved to form a true statute of religious denominations, because the development of this law has been very scarce”.

“The centre and right-wing parties do not want to discuss the issue, to maintain the current system which, although it is deficient in terms of equal treatment, they think it can benefit the majority religion”, Blázquez explained.

On the other hand, “some centre and left-wing parties have used the issue of the reform of the law as a throwing weapon, in the hands of anti-clerical groups that seek to change the entire system and implement a more secular regime that relegates religion to the private sphere, significantly curtailing the public participation of religious groups”.

Suárez believes “there is not really much debate about religious freedom” and considers that all parties with parliamentary representation “are still dogmatic and intolerant regarding religious issues. They all bulldoze their ideas when they have enough power and deny bread and water to the heretic”.

That is why there is an urgency of “entering into a full debate on the true meaning and political consequences of laicism”. Suárez regrets that “this has not been done in 2020 either”.

“Laicism is as threatened by the confessionalism of right-wing groups, as by threats to freedom of conscience from left-wing groups”, he underlines.

40 years after its approval, the Organic Law of Religious Freedom has accumulated many challenges. One of the most important, according to Suárez, is “clarifying the meaning of laicism”.

“We Protestants defend laicism and combat secularism. Spanish society needs a change of mentality that discovers the place of faith in the public arena, and the respect for the spheres of sovereignty of the churches and the state. That change requires an open social and political debate to which we Protestants have much to contribute”.

To this end, the Spanish Evangelical Alliance insists that “evangelicals must defend laicism in word and deed”. That is why the entity renounced to all state subsidies that could be available for religious organisations.

The AEE is also against the possibility of including the support to evangelical churches in the tax return because “it is not consistent for the State to act as a collector for religious institutions”.

According to FEREDE, another important challenges are “the public and social invisibility of evangelical Christians” and “the maintenance of historical stereotypes about Protestants”.

“We need to overcome our individualism to make unity projects that improve our image and allow us to be more operative in the fight against the social evils that affect us as a society”, Blázquez adds.

Monroy stresses that the main need is “to maintain the rights guaranteed by the Agreements with the state, that the Protestants gained in 1992”. He also wonders where all those people who no longer identify with Catholicism have gone. “Where are they? Surely, they are not in our churches. That is no small challenge”.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o