Preventing abuse and misuse of power in Christian ministry.

![Photo via [link]Lausanne Movement[/link].](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/66cdf5a48c866_LGAAbuLead.jpg) Photo via [link]Lausanne Movement[/link].

Photo via [link]Lausanne Movement[/link].

If there were a top ten list of issues that Christian leaders should focus on, the issue of abuse and power misuse ought to rate high on it.

In recent years we have seen cases of many trusted world-renowned Christian leaders misusing their power, often leaving more than one victim behind.

It is heartbreaking. Unfortunately, the stories we hear are likely to be just the tip of the iceberg. Furthermore, this issue is complicated by the fact that we, you and I, might be part of enabling the abuse, unknowingly harming people, whilst thinking we are doing good work.

This leaves us with a very important question: how can we prevent this from happening?

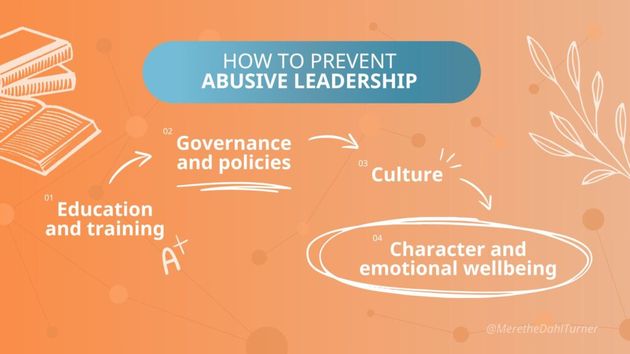

In this article I will highlight four important areas, both in preventing deliberate perpetrators and unintentional abuse or enabling of abuse. They are: education and training, policies and procedures, culture, and character and emotional wellbeing.[1]

What is abuse? That can be a tricky question to answer, as something can be profoundly harmful but not illegal.

Dr Diane Langberg, a specialist in the area of church trauma, has tried to answer that question by comparing it to what it means to be human.[2]

Abuse cannot be defined objectively since we all have different boundaries and different thresholds to what trigger feelings of powerlessness.

In the UK it is a legal requirement to have a policy to safeguard children and vulnerable adults. However, the reality is that any adult could be vulnerable to abuse, and it is difficult to find policies and procedures that cover this.

One study shows that only eight percent of churches in the US have a policy to guide the [adult female] victims.[4]

What complicates the matter is that it can take survivors years before they are able to face the reality that they have been a victim.

[destacate]The reality is that any adult could be vulnerable to abuse, and it is difficult to find policies and procedures that cover this [/destacate] Every church and organization should have a procedure that is easily accessible for everyone that describes whom to speak to, who is responsible to act, and what help is available, in all thinkable circumstances.

A challenge in Christian ministry is the blurred lines between authority and friendship or spiritual relationship.

For example, how the pastor can also be a friend, or how the ‘family culture’ is used as an excuse not to follow official procedures—’let’s sort this out as brothers and sisters in Christ.’

Culture features three important aspects. First is to make sure the organization does not have a culture of systemic abuse, where the system works to cover it up.

An example of this is how the Catholic Church has been known to send priests to a different church/parish when allegations of abuse have been made against the priests, instead of dealing with those allegations.

Second, there must be a culture of awareness. People need to know what to look out for. It is easy to think that we would all recognize an abuser, but the hard truth is even trained people are not able to recognize liars.[5]

Another hard truth is that five in six rapes against women are carried out by someone they know.[6]

[destacate]A hard truth is that five in six rapes against women are carried out by someone they know [/destacate] As one in five women have experienced sexual abuse,[7] the likelihood is that you know someone who has experienced it, and a high chance that you know who the abuser is.

And third, the organizational culture needs to provide a psychologically safe environment where it is alright to say ‘no’, even to something as little as volunteering without being made to feel guilty; an environment with no fear of being excluded if you say or do the ‘wrong thing’.

A culture where people are aware of and respect each other’s boundaries, and where they relate with one another with empathy.

Having a Christ-like character is certainly what we are looking for in all Christians. Unfortunately, predators deliberately set up a double life[8] and use a tactic known as being seen as ‘the nice one’ to prey on their victims.[9]

Their most powerful weapon is to come across as being kind and generous, so people will automatically say ‘they cannot have done such a thing!’

[destacate]Not only do predators specifically target religious communities, they also know how to act to be likeable and seen as trustworthy, and unlikely to be detected [/destacate] Ninety percent of sexual predators claim to be religious,[10] probably because Christians are seen to be more trusting and naive.[11]

So not only do predators specifically target religious communities, they also know how to act to be likeable and seen as trustworthy, and unlikely to be detected if they are lying.

For most of us it is so difficult to face the truth that the leader we know and love is also an abuser, that we automatically resort to cognitive dissonance[12] and end up rejecting the evidence.

As a result, we might even blame the victim, because we do not want to stay in the discomfort of our wrong judgement and face the consequences. So what do we do? This is where education and training are important.

Education and training are crucial elements in prevention. In terms of preventing predators many areas have already been mentioned: understanding what abuse is, statistics showing that it does happen in our midst, the difficulty in detecting lies, and the use of the tactic of being ‘the nice one’.

However, there are many other tactics predators use, often simultaneously, and the bottom line is that they use their power to try and gain control.

Any type of abuse is a misuse of power, which is the ability to influence and manipulate. Many think that to be human is to have power.[13]

Sadly, many are unaware of the power they and those around them hold, both on a micro and macro levels, and therefore also unaware of the power dynamics at play between different people.

[destacate]Any type of abuse is a misuse of power, which is the ability to influence and manipulate. Many think that to be human is to have power [/destacate] This can leave the less powerful in a vulnerable position. Micro level is about the power we hold as an individual. This can be expressed in various forms: physical (tall and muscular), verbal (loud and assertive), emotional (causing fear and showing anger), positional (possessing specialized knowledge or holding a certain title), or spiritual (eg claiming, ‘God said to me. . .’).

Macro level power can be hidden in our norms, world views, and theology. We indirectly have power through the culture we advocate for, and the focus of the theology we teach. Hiebert argues that we should be asking ourselves who is benefitting from and who is being oppressed by our theological and biblical perspectives.[14]

We also need to bear in mind how the language we use and its interpretations play an important role in this. By regularly reflecting on the above we are more likely to discern if we are causing harm and trauma on a macro level.

The last area to mention as part of education is the importance of becoming trauma-informed. Being trauma-informed means to have a basic understanding of our brain and nervous system, what trauma is, and what happens in our body when it feels threatened.

What is being in survival mode, also known as being outside our Window of Tolerance (WOT)?[15]

Our WOT has to do with our capacity to handle difficult emotions and feelings. When a situation feels too overwhelming for our nervous system, it can go into a fight-flight-freeze-fawn response (survival mode), which is what happens when we are outside our WOT.

It is important to note that we do not make a conscious choice on how to react, and it is very normal, especially for women, to have a passive response to a situation the body can perceive as threatening.[16]

A passive response means that the body is incapable of saying ‘no’, freezes, and might even go into people-pleasing, which is why it can be so hard to detect abuse.

Victims can be left thinking they ‘wanted it’ or blaming themselves, a leader might unintentionally abuse someone, and it is easy to blame victims for not saying anything. Power dynamics play a significant role because a person of authority can for many trigger a survival mode response.

The same can trigger feelings such as powerlessness, shame, and disconnection. Hence it is imperative to foster a culture without fear, and with an understanding and respect of personal boundaries.

In addition, in terms of emotional wellbeing, leaders who operate outside their WOT can accidentally become abusive if they resort to unhealthy coping mechanisms such as controlling behaviour, narcissistic tendencies, or bullying. Exhaustion is one factor that can push someone outside their WOT.

Consequently, it is important to nurture ourselves, recognize when we are operating outside our WOT, and understand what situations might trigger such a response.

This article has given an introduction on abuse and how to prevent abuse and misuse of power in Christian leaders.[17]

To prevent abuse from predators, as well as from enabling or unintentionally harming others, there are four crucial areas that we need to take note of. These are education and training, policies and procedures, culture, and character and emotional wellbeing.

We cannot expect to see positive results unless all these areas are addressed, as one area informs the other. However, we can begin to make a difference by openly talking about it, and being aware of how common it is so when someone does share their painful story, we listen carefully with empathy and do not automatically dismiss it.

Merethe Turner’s main field of interest is preventing abuse and misuse of power in missional leaders, advocating for a trauma-informed approach.

She graduated from the MA programme at ForMission College, UK, after spending her final year researching on the topic. She has since become a tutor on both the undergraduate and postgraduate courses at the same college.

Merethe worked for many years as a youth minister as well as community pastor in the UK, where she helped transform a struggling neighbourhood into a thriving community.

After living in England for ten years, Merethe is now back in her home country, Norway, with her husband and young son.

This article originally appeared in the July 2024 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis and is published here with permission. To receive this free bimonthly publication from the Lausanne Movement, subscribe online at www.lausanne.org/analysis.

1. Merethe Dahl Turner, ‘A critical evaluation of ForMission College’s strategy to prevent the abuse and misuse of power in missional leaders’ (MA diss., ForMission College, 2022), 19.

2. Diane Langberg, Redeeming Power (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2020), 7–8.

3. Turner, ‘A critical evaluation,’ 19.

4. David Kenneth Pooler, and Liza Barros-Lane, ‘A National Study of Adult Women Sexually Abused by Clergy: Insights for Social Workers,’ Social Work 67, no. 2 (January 2022), 123–133.

5. Anna Salter, Predators (New York: Basic Books, 2003), 40.

6. ‘Statistics about sexual violence and abuse,’ Rape Crisis UK,.

7. ‘Statistics about sexual violence and abuse,’ Rape Crisis UK,

8. Salter, Predators, 31.

9. Natalie Collins, Out of Control, (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2019), 18–19.

10. Glen Scrivener, ‘Church abuse: protecting ministries, destroying souls,’ interview with Diane Langberg, The Speak Life Podcast, Podcast audio, 23 March 2021,

11. Salter, Predators, 139; Wade Mullen, Something’s Not Right: Decoding the Hidden Tactics of Abuse—And Freeing Yourself from Its Power (Illinois: Tyndale House, 2020),

12. Shira Berkovits, ‘Institutional abuse in the Jewish community,’ Tradition 50, no. 2 (2017), 12.

13. langberg="">13. Redeeming Power, 3.

14. Paul G. Hiebert, Transforming Worldviews (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 226.

15. Daniel Siegel in Aundi Kolber, Try Softer: A Fresh Approach to Move Us Out of Anxiety, Stress, and Survival Mode—And Into a Life of Connection and Joy (Illinois: Tyndale House, 2020), 71.

16. Robert Scaer Natalie Collins, Out of Control, (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2019), 173.

17. Editor’s Note: See ‘The Transcendent Culture of Servant Leadership’ by Mary Ho in Lausanne Global Analysis, March 2020,

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o