Our stories cannot help but echo the universe’s defining moment.

Christ appearing to the Apostles after the resurrection, by William Blake.

Christ appearing to the Apostles after the resurrection, by William Blake.

“Why is mythology everywhere the same?” This may sound like a simplistic judgment – there are so many myths across history, from the Hindu Vedas to the Nordic tales and the Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic.

But the person who raises the question is Joseph Campbell, a Columbia University expert in comparative mythology and, according to Campbell, no matter which folk traditions are surveyed, from the peoples of Congo to the legends of the Eskimos, “it will always be the one, shape-shifting yet marvellously constant story that we find…” [1]

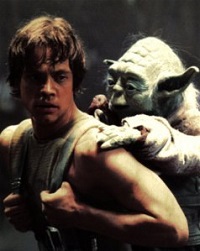

Campbell’s major book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, plots these common themes in the universal figure of the hero, whose adventures follows similar steps even in the most varied cultural settings: he receives a call to adventure, and after initial reluctance, he crosses the threshold to his journey. Here he faces numerous trials and meets forms of gods or goddesses, who mentor him and help he understand his mission, until he returns to reality with a message to proclaim or a mission to fulfill, and saves the community from its perils. (When George Lucas crafted the story for Star Wars and its hero Luke Skywalker, he leaned heavily on Campbell’s reconstructed hero’s journey).

Luke Skywalker and Yoda, in Star Wars.

Luke Skywalker and Yoda, in Star Wars. So why is mythology everywhere the same? To explain our common stories, Campbell uses the theories of psychoanalysis, especially the views of Carl Jung, to explain the common source of our kaleidoscopic but similar myths and stories. Myths are reflections of our social mind, of archetypal urges deep beneath our psyches. In Campbell’s words, “They are spontaneous productions of the psyche, and each bears within it, undamaged, the germ power of its source.”[2]

Ok, these stories originate in our minds… but the question still begs itself: why? Why does the human mind keep producing these stories? Why are myths everywhere, and why are they so similar? What do these archetypes point to?

I believe a person’s journey will illuminate us here. C. S. Lewis was another expert in comparative mythology, and as he started to read the New Testament as an atheist, he was at once startled at how different and yet how similar the Gospels were to ancient myths. At first he was struck by how unlike they were to the metaphysical and fantastic shapes of myths: they smelled like real events, taking place in a specific place and a specific time, not like the pre-time, allegorical epochs of myths. “I have been reading poems, romances, vision literature, legends, myths all my life. I know what they are like. I know that none of them is like this [the New Testament record].”[3]

Yet even as Lewis noted that the Gospels smelled like real history, he could not miss the common themes it shared with the great myths. Especially, he could not miss the central plot of “the Dying and Reviving God” common to so many folk traditions. Lewis’ initial reaction was dismiss the story of Jesus as another myth, but as the historicity of the Gospels bogged him, he was further disturbed by a comment he once heard. “The real clue had been put in my hand by that hard-boiled Atheist when he said, ‘Rum thing, all that about the Dying God. Seems to have really happened once’.”[4]

C.S. Lewis.

C.S. Lewis.I agree. That hard-boiled atheist is just right. How else would you explain variations of same stories cropping up again and again everywhere? They must be reflections, fragments of the Great Story the human psyche captures and different peoples emphasize differently. They are echoes, daydreams that emerge in fantastic forms from the unconscious, but which articulate the central themes of the human drama – our ideals, perils and longings for our Savior –, packaged with the infinite creativity of the human genius and its multiform cultural riches.

For an expert in mythology like Lewis, the multitude of human myths were not contradictions, but preparations for the true story. They were early echoes of God’s thunderous arrival on the planet in the person of Jesus Christ. “In my mind,” wrote Lewis, “the perplexing multiplicity of ‘religions’ began to sort itself out… The question was no longer to find the one simply true religion among a thousand religions simply false. It was rather, ‘Where has religion reached its true maturity? Where, if anywhere, have the hints of all Paganism been fulfilled?’” And as Lewis surveyed the ages, and found a historical event that culminated all the best of human aspirations and longings, his conclusion could not have been different. “If ever a myth had become fact, had been incarnated, it would be just like this… Here and here only in all time the myth must have become fact; the Word, flesh; God, Man.” [5]

So why are myths so similar? Because they resemble the history of the universe, the drama of our creation, fall, and God coming to rescue us. They sprout little curious buds, small insinuations in delicate poetry, that came to full bloom when eternity entered time, when God became man, and the grandiosity of the myths met the ordinariness of history, and the Dying and Reviving God really did die on a cross in a Friday afternoon in Jerusalem in the first century, and revived on the early hours of the following Sunday. The grand plot of myth took place in history, and our stories cannot help but echo the universe’s defining moment.

[1] Joseph Campbell, The Hero With a Thousand Faces (Novato, Calif.: New World Library, 2008), 1-2.

[2] Ibid., 330, 2.

[3] C. S. Lewis, “Modern Theology and Biblical Criticism”, in Christian Reflections (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1967), 155.

[4] C. S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of my Early Life (New York: Hancourt, 1955), 235.

[5] Ibid.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o