Guatemala is the country with the highest percentage of evangelicals in Latin America. However, it has one of the highest rates of inequality, violence and corruption.

President Jimmy Morales, an actor, played an evangelical pastor in a film.

President Jimmy Morales, an actor, played an evangelical pastor in a film.

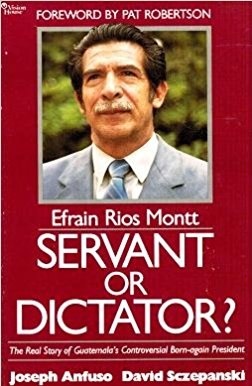

Rios Montt, the general who came to power in Guatemala with a coup d’état, has died. He was known for his evangelical faith, but also for the accusations of genocide in what is considered one of the bloodiest dictatorships of the 1980s.

Guatemala is not only the country with the highest percentage of evangelicals in the whole of Latin America, but it is also the country in which they are most active in politics. The country however has one of the highest rates of poverty, inequality, violence and corruption.

The current President of Guatemala, the former actor Jimmy Morales, made a film about a pastor in the midst of a crisis. “Fe” (Faith) is the first fictional feature film by the young documentary maker, Alejo Crisóstomo, who is half Guatemalan, half Chilean. The film tells the story of an evangelical pastor in the midst of crisis.

Ríos Montt was not only known for his evangelical faith, but for the accusations of genocide.

Ríos Montt was not only known for his evangelical faith, but for the accusations of genocide.Through a series of circumstances, linked to his circle of friends and the family of his wife, Arturo Herrera is one of those pastors with a certain amount of influence in Guatemalan high society. He is a dedicated man of faith but, in his honesty, he feels that he could do more and he wonders why God has given him the mission that he feels called to.

One day, he is invited to preach at the Ciudad de Guatemala prison where he meets Beto, a fisherman from Rio Dulce accused of murdering a thirteen year-old girl. The pastor interprets this meeting as a message from God and, once the fisherman gets out of prison, he decides to help him by giving him a home and a job in his church. His family and the congregation challenge his decision, while what he holds to be true is shaken when he discovers that a crime has been committed close to his church.

MEGACHURCHES

Even though figures vary – as they always do– from thirty to fifty per cent of the population, there is no doubt that Guatemala is the Latin American country with the largest proportion of evangelicals. The most conservative statistics estimate their number at least thirteen million. According to the Evangelical Alliance, there are some 27 000 evangelical churches, although some of them prefer to simply call themselves Christian.

I recently had the opportunity of visiting a megachurch for this first time. The church is popularly known as the Frater (short for Fraternidad Cristiana), and there I was able to speak with Pastor Jorge López, who founded the church in 1978, with only 22 members. More than 12 000 members now meet in a gigantic auditorium, the luxury of which took me somewhat by surprise. In a country where more than 56% of the population lives below the poverty threshold, it is amazing that all this has been built without foreign money.

Church members include people as influential as a judge on the Supreme Court – the President of the last Electoral Supreme Court was an evangelical Christian–. The building is, by the way, surrounded by armed security agents, just like many of the other places I saw there. The streets are full of soldiers with machine guns, ready to shoot, and there is a general feeling of insecurity at the longstanding problem of latent crime and violence. There are some areas of the city that even the police are afraid to go into.

THE OTHER SIDE OF GROWTH

According to Israel Ortiz, Director of the Centro Esdras (a bible training centre in Guatemala City), “some pastors boast about evangelical growth as evidence of God’s power”, so much so that “they have even claimed that Guatemala is the New Jerusalem of America”. For him, “however, reality indicates that this presence has not had any effect on social, economic, cultural and political structures in society”, given that “quantity does not ensure a qualitative presence in society”.

In fact, for this Guatemalan theologian, “quantity, far from being the key to change, can become a refuge for religiosity without commitment and the absence of any real responsible action in the world”.

The film shows the violence this central American country experiences.

The film shows the violence this central American country experiences. The evangelical obsession with numbers goes hand-in-hand with a form of “prosperity gospel”, as proclaimed by Cash Luna, the pastor of the Casa de Dios church, which has already outgrown Frater – where he became a Christian –, with 16 000 members and 25 radio stations throughout the country.

The analysis given by SEPAL – the Evangelistic Service for Latin America – of the “state of the Evangelical Church in Guatemala”, is that the Church is growing numerically, but not in terms of its quality of life. Alejo Cirsóstomo, who is based in Costa Rica, was very intrigued by the speed with which the evangelical movement had grown and he wanted to find out more about it. In parallel, a book has been published in Costa Rica about the growth and drop-out rate in the Costa Rican church. Both analyses consider that the problem lies in a lack of discipleship.

BEYOND PREJUDICES

In Fe, Crisóstomo wanted “the main character to be an evangelical pastor, a family man, taking us on a journey in which we are constantly passing judgement on the basis of prejudices, which are sometimes even stronger than faith”. He wanted to make a film about “the power of prejudice in human relationships”, and about the “foundations on which faith and truth are built”.

The director of the film is Alejo Crisóstomo.

The director of the film is Alejo Crisóstomo.It is a project to which he has dedicated five years of his life, after his cinema debut with two short films and a documentary on Guatemala as a pluricultural and multiethnic country. He has meanwhile also participated in the international project “Life in a day”, which premiered in 2011.

Crisóstomo says that he identifies with the conflicts faced by various of the film’s characters, especially the pastor: “He has the same conflicts and doubts as me; about vocation, the reason why we are on earth, the innocence of wanting to do the right thing, and the weight of a society that demands a perspective that we don’t share”.

OUR PLACE IN THE WORLD

The main character in the film Fe wonders about his place in a world dominated by violence and prejudices. Israel Ortiz’s analysis of evangelicals in Guatemalan politics comes to the conclusion that “save for some honourable exceptions, most of them have had little impact”, even “those who have had the opportunity to trigger substantial change, have achieved little”. How is this possible?

The explanation, for the director of the Esdras Centre, is that “we, as evangelicals, have not been the salt and light of the earth as the Word calls us to be” (Matthew 5:13–16). The fact is that “many Christians not only don’t differentiate themselves from the rest of society, but they have been entrapped by ideas, conducts and lifestyles in the prevailing system”. It is therefore “difficult for us to live according to the ethical values of the Kingdom of God”.

A moment of the production of the film Fe.

A moment of the production of the film Fe.We can be in no doubt that the Holy Spirit is driving a revival in countries like Guatemala. The question that people like Ortiz are asking is whether that experience is in line with the Gospel.

In other words, whether it is producing substantial changes in personal and community life, as in the churches of Jerusalem, Antioch and Thessaloniki, featured in Acts of the Apostles. Given that, as this Guatemalan theologian observes, “a revival should be seen through changes in the ways of thinking and living among believers and in their environments”.

THE POWER OF THE GOSPEL

The conclusion could not be clearer: “If we do not see a greater impact in our countries, we need to ask ourselves whether believers experience a real conversion or only a religious experience”. Jesus took no account of the numbers that followed Him and said they believed in Him (John 2:24). He would instead confront them and his ten disciples openly (6:60–67). So what should we do?

We should proclaim the Gospel, which is the power of God to save and transform lives. The conversion of Zacchaeus (Luke 19:1–10) demonstrates the transformative power of the Gospel. His meeting with Jesus changed his life. He not only understood that the justice of the Kingdom required restitution, but the grace of God in Christ led him to distribute his wealth among those that he had defrauded.

This is the greatest form of justice, which Jesus said should differentiate his disciples from the religious people of his time (Matthew 5:20). Parker says that “the Gospel brings solutions to the problem of suffering and injustice, but it does so by first resolving a deeper problem: the relationship of mankind with its Maker”. If the Gospel does not change us, what can?

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o