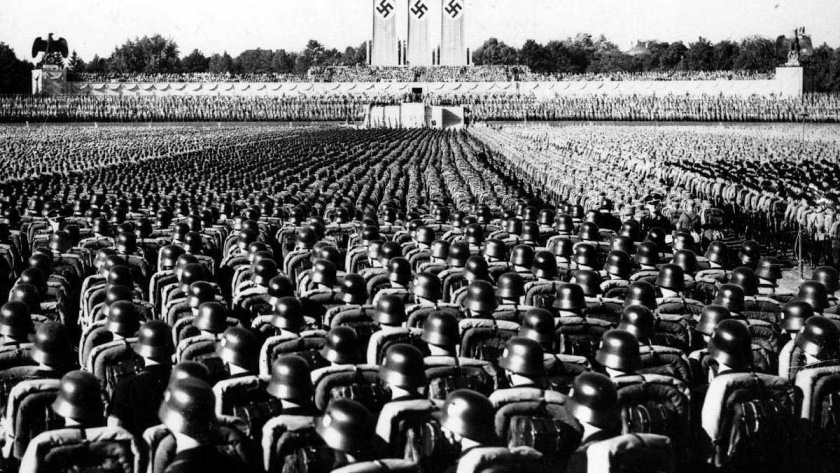

The film presents the provocative thesis that, beyond ideologies, flags and uniforms, even beyond anti-Semitism itself, lies the worship of the leader.

What is the appeal of an empire that turns its followers into blind devotees while its enemies see it as the personification of evil? This is the question raised by the new film about the Nuremberg trials.

Based on the testimony of psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who was responsible for determining whether the Nazi leaders were mentally responsible for their actions, the film presents the provocative thesis that, beyond ideologies, flags and uniforms, even beyond anti-Semitism itself, lies the worship of the leader.

Everything is explained by the narcissism on which power is based, provoking both fascination and rejection.

All Evangelical Focus news and opinion, on your WhatsApp.

At a time when megalomaniacal, populist leaders who have turned politics into an exercise in idolatrous fanaticism abound, James Vanderbilt's work has much to say.

The rejection of Kelley's book in the United States following the trial is due to the mere suggestion that the nightmare of the Second World War could happen in his own country if a leader who does not tolerate criticism is worshipped.

It is curious how Nazism continues to perplex us. This year, four of the most important essays published in Spanish tackle this very issue.

Following the seminal study by Dutch author Frank Dikötter (Dictators: The Cult of Personality in the Twentieth Century) on what is the common denominator among tyrants; we end 2025 with the translation of Volker Ullrich's much-discussed work on how democracy in Germany was destroyed in thirty days with Fateful Hours: The Collapse of the Weimar Republic.

And after Takeover. Hitler's Final Rise to Power (Timothy W. Ryback), Laurence Rees enters The Nazi Mind, which led to the exile of so many German thinkers in February 1933, by Uwe Wittstock.

All these essays agree that skill alone is not enough to access power, nor is the exercise of absolute domination. History is full of countless short-lived tyrants who have been forgotten by most of us.

According to Dikötter's thesis and the film Nuremberg, based on Jack El-Hai's 2013 book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, it is the worship of personality that deifies the powerful, turning them into providential guides.

Ideology is irrelevant; the question is not only how to conquer power, but also how to maintain it by presenting oneself as indispensable, as the saviour of the country or the embodiment of the national spirit.

The role of terror used by dictatorial regimes in their purges and genocides is not ignored or underestimated. These authors claim that violence alone cannot explain these leaders' longevity in power or the almost religious adoration they receive.

Politics is clearly a theatre, but dictatorial power takes this performance to a level that demands unconditional obedience. That is why they provoke such extreme reactions: blind devotion or visceral hatred.

Vanderbilt's film cannot compete with Stanley Kramer's classic, nor does it attempt to.

In Spain during Franco's dictatorship, Judgment at Nuremberg was given the misleading title Winners or Losers? Rather than being a translation, this seems to be an ambiguous description of Nazism itself.

The legendary film, starring Spencer Tracy, does not actually recount the trial of the top Nazi leaders, but rather a follow-up trial in 1948 of four judges complicit in sterilisation and ethnic cleansing policies. Between 1945 and 1948, there were thirteen trials against those responsible for different Nazi institutions.

Nuremberg (2025) is not an updated version of the entire process, as the 2000 miniseries of the same name intended to be.

What interests the screenwriter of Zodiac (David Fincher, 2007), is the investigation by psychiatrist Douglas Kelley into the enigma of evil that led Nazi leaders to commit crimes against humanity during the Second World War.

Moreover, it explores the love-hate relationship between the second-in-command of the Nazi regime, Hermann Göring – played here with theatrical gestures by Russell Crowe – , and the American army colonel psychiatrist –played by the expressionless Rami Malek–, who had to assess the prisoners' mental state to prevent them from taking their own lives, as Hitler, Goebbels and Himmler had done.

The trial began on 18 October 1945 and culminated in the reading of the verdict on 1 October 1946. Of the twenty-two defendants, twelve were sentenced to death by hanging. Göring, like Kelley, committed suicide by taking cyanide in response to the Americans' rejection of the idea that there could be a Hitler in the United States.

Three Nazi leaders were sentenced to life imprisonment, including Rudolf Hess in Spandau, while only three were acquitted.

However, the trial laid the foundation for an international court, such as that in The Hague, a project that was rejected by the United States, China, Russia, India, Israel and Turkey. Until such a right is accepted, there is no justice other than the power of the strongest.

The terrifying conclusion that Kelley reached in his book, 22 Cells in Nuremberg: A Psychiatrist Examines the Nazi Criminals (1947), is that the Führer's henchmen were not monsters, but rather ordinary people with excessive narcissism.

Nazis hold a special place in our imagination. We believe they live in a world apart, created by a unique confluence of time and circumstances that led to unrepeatable horrors.

This summer, I had the opportunity to visit Nuremberg with my family. We stood in the room where the trials were held and followed the countless panels illustrating what happened during those proceedings.

One wonders whether Nazism was unique. The Holocaust – a nice name for something so terrible – seems to be the result of anti-Semitism, which one doubts will ever produce such a genocide again, even though the term is used over and over again in any war.

What surprises any reader of a biography of Hitler is what Kelley discovers about Göring: anti-Semitism is not at the root of Nazism. It is merely a conspiracy theory in which Jews become scapegoats for the ambition of an opportunist like Hitler.

Ideology often blinds you to reality. It is about the worship of an individual, something that we are all sadly very familiar with due to our insatiable ego.

Kelley was not a Christian, but the arrogance of Göring is familiar to any believer. The religious and spiritual world is full of leaders with excessive egos. Pride is not exclusive to political and economic power. It permeates academia and taints philanthropy to the extent that nobody considers others first.

Our favourite topic is ourselves. We are our main concern. We never tire of talking about ourselves.

Beyond all discourse and labels, there is only one explanation for our words and thoughts: What benefit do we get from all this? If it has nothing to do with me, I'm not interested.

Human beings are so predictable. There is nothing more monotonous and repetitive in our existence than the way we are always looking inwards. We delight in meeting ourselves.

Behind all our good intentions and fine words, all we have is self-centredness. On top of that, they tell us that we don't love ourselves enough and that we lack self-esteem. That's how foolish our psychology is.

Nuremberg concludes with a quotation from the British philosopher, historian and archaeologist R. G. Collingwood (1889–1943): “The only clue to what man can do is what man has done”.

As my teacher in London Stott used to say, no doctrine of the reformers is more fundamental to Christianity than the total depravity of human beings. The problem is that many people do not understand what that means.

It does not mean that we are as evil as demons, incapable of doing any good; but rather that nothing in humanity is free from the effect of the evil that the Bible calls sin.

“All have turned away; there is no one who does good, not even one” (Romans 3:12). Evil is subtle. We think it is easy to identify, but it is not. As Hannah Arendt reminds us, it is banal and ordinary. When the Allies discovered the extermination camps in 1945, men such as Eisenhower could not believe that the Nazis were capable of such atrocities.

In the film, Kelley initially treats Göring like a lab rat (“If we can define evil psychologically, we will ensure that none of this can happen again”), but Göring turns out to be a normal person, even more charming than Kelley.

At the end of this two-and-a-half-hour film, which flies by, we see the same documentary that was screened on 29 November 1945 at the Nuremberg trials. It shows images of the Nazi concentration camps, with burned bodies, skeletal survivors, gas chambers, huge piles of bones, and heaps of rotting flesh being pushed around by bulldozers.

Watching it provokes a silence akin to the one I experienced when visiting Dachau near Munich this summer. As historians say, in the face of such evidence, denial is impossible. Chesterton said that original sin is the only Christian doctrine that does not require faith to believe.

The ending of Nuremberg is devastating. It shows why this film was made now. It is not just a matter of historical curiosity. It speaks about today.

Back in the United States, Kelley is interviewed on the radio about his 1947 book. The presenter says to him, “You have to admit that the Nazis were unique people”. To which the military psychiatrist replies: “They were not unique. There are people like the Nazis in every country in the world today”. The interviewer replies: “Not in America”.

Kelley insists, “Yes, in America. Their patterns of behaviour are not unfamiliar to us. There are people who want to be in power. You say that this is not possible here, but I am sure that there are people in America who would gladly trample on half of the American public if they could take control of the other half”.

Unsurprisingly, when the commercial break comes, the psychiatrist is politely asked to leave the studio, bringing the interview to an end.

Nobody wants to hear that we are not good and that “sin dwells in me” (Romans 7:20). The “fascists” are always the “others”, those who do not think like me. We have bought into the fantasy of our moral superiority, thinking that our “values” are better than those of any previous generation.

We are so inflated and full of ourselves that we cannot even imagine that the evil we seek in our “witch hunts” of abusers is also in our own hearts.

“Wretched man that I am!” says the Apostle Paul. “Who will rescue me from myself?” (Romans 7:24). The only possible salvation is not within us, but “in God through Jesus Christ” (v. 25). In order to understand the Good News of Christianity, we must first accept the Bad News: that we cannot free ourselves.

If God came into this lost world in the person of Jesus Christ, it is because He had no other choice; “what is impossible for men is possible for God” (Luke 18:27). That is our only salvation!

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o