We are finally witnessing a complex and adult work, which cannot be reduced to the simplistic schemes to which victimhood seems to have condemned us lately.

The problem posed by 'Oppenheimer' is the very dilemma of forgiveness.

The problem posed by 'Oppenheimer' is the very dilemma of forgiveness.

It has been a long time since the Oscars awarded a film as solid as Oppenheimer.

In the midst of so many slogans and the increasingly suffocating dictatorship of "political correctness" -whereby every work has to represent all diversity of race, gender and sexual orientation-, we are finally witnessing a complex and adult work, which cannot be reduced to the simplistic schemes to which victimhood seems to have condemned us lately.

Christopher Nolan's work is an authentic cinematographic prodigy, perfectly assembled, that makes you spend three hours without realizing it, before the sole spectacle of continuous conversations that awaken a growing curiosity, even if you don't have the slightest idea of science.

His obsession with analogous methods and the perfectionism with which he aspires to imitate his master, Stanley Kubrick, have never worked as well as in this film, a true masterpiece.

His intricate visual and narrative experiment had nothing to fear from the vacuous, ambiguous entertainment of Greta Gerwig's Barbie, justly forgotten at this year's Oscars, where the growing foreign presence in the Academy, something immune to the fashions that have prevailed in Hollywood lately, has an increasingly heavy weigh. Neither the director nor her protagonists have received any awards for the film that took the US by storm this summer.

I can't think of a better actor to play Oppenheimer than Irishman Cillian Murphy, not only for his slender frame, but for the chameleon-like appearance with which he blends in with his characters.

The enigmatic figure of the "father of the atomic bomb" has something of that strange and elusive character with which the actor always embodies his roles.

Surrounded by scientists, military men, politicians, wives and lovers, his identity seems to be lost in a tragic destiny, worthy of the myth referred to in the work on which the film is faithfully based, the great book by Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, which presents him as an American Prometheus.

Born in 1904 into a prosperous Jewish family of Prussian origin in the liberal atmosphere of New York, he is an art collector with no religious practice. He led a promiscuous life, but was interested in literature and mysticism, quite unaware of the world around him until the 1930s.

His education at the School of the Society for Ethical Culture, next to Central Park -where Tim Keller preached so much- led him to study chemistry at Harvard.

His time at Cambridge University is as traumatic as the film reflects, as he really had such a bad relationship with his tutor, Patrick Blackett, that he effectively tried to poison him, according to his friend Francis Fergusson.

Like so many American Jews, Oppenheimer is clearly left-leaning, though he never became a member of the Communist Party, like his wife. It is curious that the fascination of conservative Protestant America with Judaism goes hand in hand with a radically opposite political orientation, since most American Communists are Jewish.

They have that ”Old Testament” social and collective conscience, whereby Oppenheimer distributes the enormous wealth he inherits with his brother to all sorts of humanitarian causes, rather than leaving it, as most do, to his children.

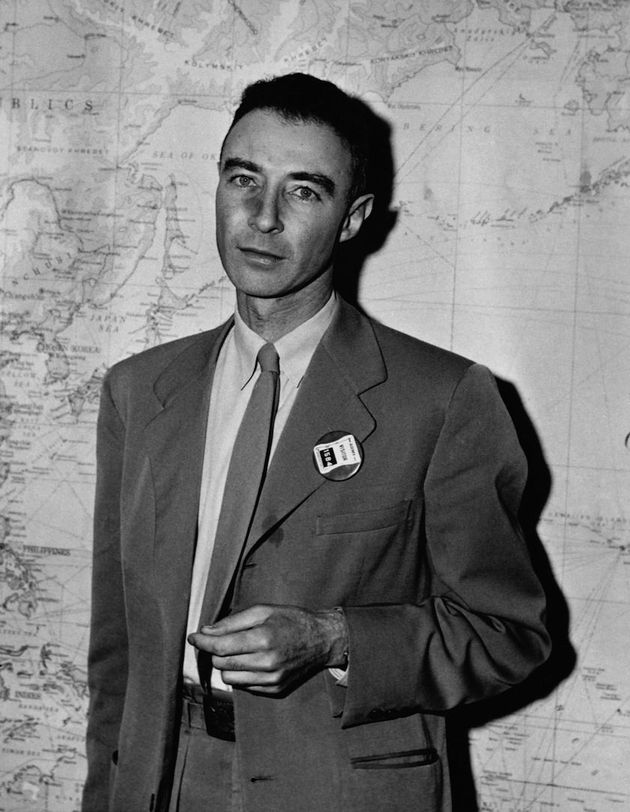

[photo_footer] Christopher Nolan's work is an authentic cinematic prodigy, perfectly assembled, that makes you spend three hours without realizing it.[/photo_footer]

After his doctorate in Germany with atomic energy scholar Max Born, Oppenheimer teaches at Berkeley University in California, not Princeton, as the film suggests when he meets Einstein.

It is after Los Alamos that he goes there, where Einstein works under his supervision. The Manhattan Project is born in New York, as the name suggests, but spreads to other locations, such as Los Alamos in New Mexico. President Roosevelt calls him to lead it, after already joining the project in the Big Apple.

The use of the bomb he had developed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki aroused in him doubts that led him to oppose the hydrogen bomb and the proliferation of nuclear weapons in the "cold war" with the Soviet Union.

With President Truman, he then went from being an "ally" to an "enemy". Tormented with guilt, he believes, in the words of the Bhagavad-Gita, that he has "become death, the destroyer of worlds".

Having been "blacklisted", he has to leave the investigation, not being reinstated until the arrival of President Kennedy, shortly before he died of cancer in Princeton in 1967.

While atomic energy is one of the "cleanest" in existence, its devastating effect is evident, as evidenced by its use in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Its explosion does not immediately bring an end to World War II, as Oppenheimer had hoped.

Japan does not surrender. However, the "cold war" does not break out because of the deterrent effect of the possible use of such weapons of mass destruction. Oppenheimer was a theoretical physicist.

He had to experiment in order to know the risk that the use of such energy could bring. By exploding the bombs, many feared he could destroy the entire planet.

[photo_footer]President Roosevelt calls him to head the Manhattan Project in the Los Alamos desert in New Mexico..[/photo_footer]

His relationship with the American Jewish Communist psychiatrist Jean Tatlock is fascinating. The daughter of a Berkeley literature professor, she has a passion for Oppenheimer, despite her bisexual orientation and the scientist's marriage to another woman.

At Berkeley he meets a communist student named Katherine Puening -he called her Kitty, and he was known as Oppie since he was called Opje at the Dutch university in Leiden-.

She was twice divorced and had a partner who died in between these two marriages, and she was fighting for communism in the Spanish Civil War. Oppenheimer himself supported the Republican cause against Franco's army.

Oppenheimer's relationship with Tatlock continued until her suicide in the midst of a severe depression. The night they spent together in San Francisco -key to the scientist's trial in the "witch hunt" over the FBI's investigation into possible secrets he had passed to Russia- was not at the Fairmont Hotel in the film, but at her flat on Telegraph Hill, next to Coit Tower, where she died. In my passion for the history of that city, I have visited both sites, when I was at Jesuit University.

Tatlock introduces Oppenheimer to the poetry of the Puritan preacher and poet John Donne. One of his verses gives name to the first nuclear experiment, Trinity, after Donne's devotion to the three-person God.

Two images of Tatlock's drowning death are seen in the film. One shows hands in black gloves pushing her head into the bathtub. It comes from the "conspiracy theory" that she was killed by agents of the American intelligence service. It also appears in the tv show Manhattan.

[photo_footer]Oppenheimer's life is marked by a stormy relationship with the American Jewish communist psychiatrist Jean Tatlock...[/photo_footer]

When Kitty discovers that Oppie was in a relationship with Tatlock until her death, he appears shocked, but his wife tells him in the film: "You can't commit a sin and expect others to have compassion for you".

The problem Oppenheimer raises is the very dilemma of forgiveness. The scientist is a lapsed Jew, fascinated by Hindu spirituality, who has no hope of redemption that would bring absolution for his sin. There is no penance that can bring him the relief of forgiveness.

His legacy, on the one hand, warns us of what C. S. Lewis called in The Abolition of Man the danger of "scientism": the idea that the solution to the world's problems lies in scientific or technological development.

As New York professor Neil Postman says, "a new technology sometimes creates more than it destroys; sometimes it destroys more than it creates; but it never acts in only one direction".

As Postman says, "technology always has unpredictable consequences, because it is not clear at the outset who or what will win, or who or what will lose.

Nolan's masterful film shows the moral challenge of our actions, both personal and social. It gives us examples of decisions that have an extraordinary effect on life and history. What we are shown is our weakness. We can be powerful and brilliant like Oppenheimer, but weak and foolish in our choices.

[photo_footer]Like so many American Jews, Oppenheimer is clearly left-leaning, although he never became a member of the Communist Party, like his wife..[/photo_footer]

When the general, surprisingly played by Matt Damon, asks the scientific team what the risks are, they tell him "almost zero". The military man exclaims: "It would be nice if there were none!”.

How do you calculate the risks, when the stakes are so high? Oppenheimer's logic is: "I don't know if we can be trusted with such a weapon, but I know the Nazis can't". He believes that "we have no choice".

By the Grace of God and perhaps against all odds, nuclear weapons have had a deterrent effect so far.

In one sense, Oppenheimer is a horror film. Watching the reaction so powerfully conveyed by Gary Oldman as President Truman, one has little confidence in what the powers of this world can do with such weapons. Proud and glib, bellicose and ambitious, it is scary to be in such hands.

The politician can't stand the guilt of the scientist, but given Oppenheimer's moral character, you can't trust his fidelity either. You are horrified by the decision-making ability of such weak people.

When they discuss where to drop the bomb, the "secretary of war" says not in Kyoto, because it is a "nice city" where he spent his honeymoon.

And behind the "communist paranoia" is the pettiness of characters like Robert Downey Jr. (Lewis Strauss), proud, cynical and resentful. The highest political ideals are corrupted by our human misery.

Scripture has no simple answers to such complex questions as these, but it shows us that God has not abandoned His creation (Matthew 5:49b; 5:25-34). The Lord is in control of the world.

There is an end to this time, but it is He who determines the hour. And we are to live in the light of that day (2 Peter 3).

Even if we do not face ethical questions of Oppenheimer dimensions, we have no guarantee of the outcome of our decisions in our work, personal lives and political choices.

We are easily swayed by ambition, fear and foolishness. We are like "clay jars" (2 Corinthians 4:7). Who is up to the task (v. 16)? Our hope is in God's power, not in ourselves. Therefore, let us not lose heart! (v. 1, 16).

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o