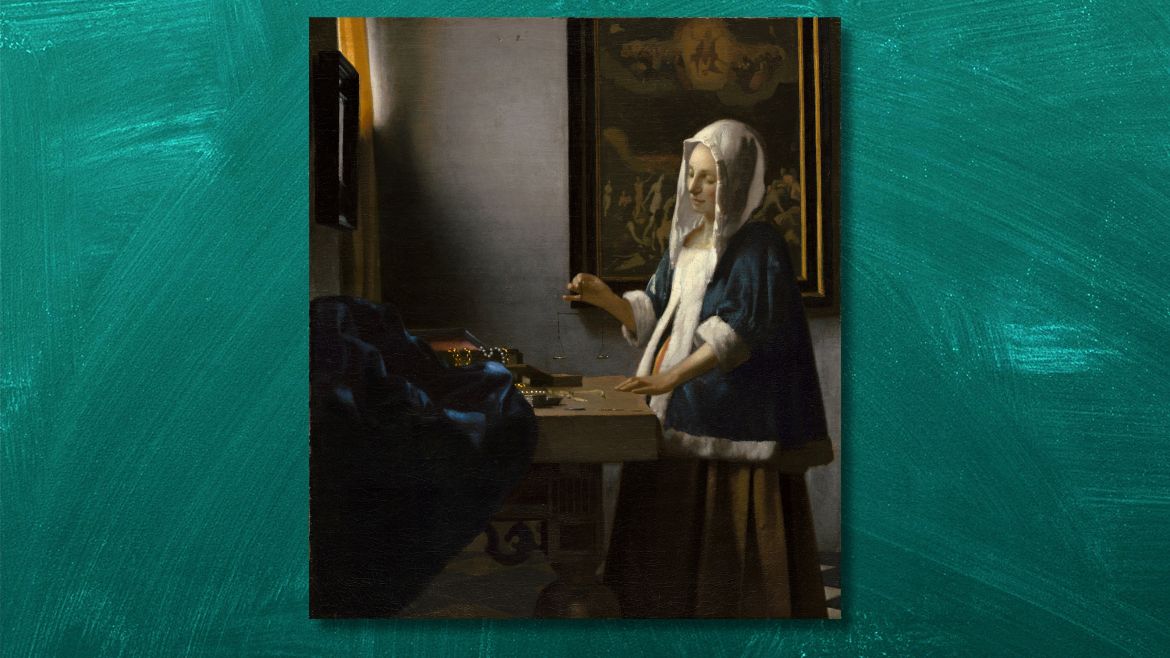

Johannes Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance offers a quiet visual parable for this moment. As we face yet another new year of war, polarisation and distrust, we need reflection which goes beyond personal self-improvement.

Johannes Vermeer - Woman Holding a Balance. Photo: Google Art Project, Public Domain.

Johannes Vermeer - Woman Holding a Balance. Photo: Google Art Project, Public Domain.

The New Year is an occasion to reflect and make resolutions – to search our souls, and ask ourselves if we are on the right path.

Johannes Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance offers a quiet visual parable for this moment. In his new book about the Dutch master which I cited last week, Andrew Graham-Dixon suggests the woman represents Mary, sister of Martha, searching her soul, weighing not gold but her own conscience. Behind her is a painting of The Last Judgement.

Perhaps as we face yet another new year of war, polarisation and distrust, we need reflection which goes beyond personal self-improvement.

All Evangelical Focus news and opinion, on your WhatsApp.

Perhaps we should ask the question Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky put to his fellow Ukrainians: How can we put our house in order?

Sheptytsky is one of the inspirational figures I was introduced to this last year while visiting Kyiv. Not in person unfortunately. He died in November 1944. He had survived two World Wars and the Holodomor during Stalin’s reign of terror, when Moscow starved millions of Ukrainians to death in the 1930s.

He was the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, an Orthodox church which relates to Rome, strategically straddling the spiritual fault-line of the Great Schism.

He was perhaps the most influential figure in the Ukrainian Church in the twentieth century.

Writing amid the upheavals of empire, war, and national rebirth, Sheptytsky insisted that lasting renewal began with personal conversion, not with institutions alone.

A society cannot be healed, he argued, if its citizens refused to examine their own hearts. Moral decay at the top was sustained by moral indifference below. Before demanding justice from others, we must ask whether we live justly ourselves.

For Sheptytsky, this inner ordering radiates outward. The health of a nation rests on the health of its families, and that rests on the integrity of persons.

Truthfulness, fidelity, restraint, and responsibility are not private virtues; they are the quiet architecture of public life. When homes are ruled by fear, dishonesty, or neglect, the state will eventually reflect the same disorders.

Self-examination does not mean withdrawal from the world. On the contrary, Sheptytsky warned that piety divorced from social responsibility becomes a betrayal of faith.

Justice, mercy, and humility —echoing the ancient words of the prophet Micah— must shape economic life, political decisions, and the way power is exercised.

Compassion without justice sentimentalises suffering; justice without mercy hardens into cruelty; humility without courage slips into passivity.

Soul-searching must also extend to our political choices. Sheptytsky respected authority but refused to sanctify it. Leaders, he insisted, are servants of the common good, not its owners.

Citizens, whether believers or not, therefore have both the right and the duty to hold power to account—peacefully, truthfully, and persistently. Silence in the face of injustice is not neutrality; it is complicity.

A Christianity that blesses power while refusing to call it to repentance risks becoming chaplain to the very abuses it once resisted. When church leaders demand repentance from society but exempt those they support politically, the credibility of their witness erodes.

Some of us may have supported or voted for leaders in good faith because they promised to restore what was broken in society.

If in practice, however, they have pursued policies marked by discrimination, distortion of truth, abuse of human rights, self-enrichment, vengeance and contempt for justice, our response should be prophetic witness and repentance.

Too often this year we have seen silence, rationalisation, or outright defence of behaviour that stands in stark tension with biblical norms.

We have seen widespread reluctance to name moral failure in political leadership—particularly when that leadership promises our group power, protection, or cultural advantage.

Soul-searching of another sort is what Robert Schuman called for when he said the European project must not just be economic and technological – it needed a soul.

When president of the European Commission, Jacques Delors called religious leaders to help find a soul for Europe, i.e. spirituality and meaning – without which he warned ‘the game would be over’.

We are sensing a new focus for us in the Schuman Centre this year, responding to the challenge these two Fathers of Europe left us: the search for Europe’s soul.

In particular with Ukraine as a laboratory. What will it mean to rebuild that war-torn nation on spiritual and moral foundations? And what could that mean for other European nations?

Ukraine’s struggle and sacrifice have awakened a search for moral renewal. Church and political leaders are reaching out for support beyond their own borders.

The ideals of the Maidan revolutions — dignity, justice, freedom, truth — reflect a deep moral and spiritual impulse. These ideals draw from the biblical vision of the human person as created in God’s image, the foundation of human rights and equality.

Without this transcendent reference, the words freedom and dignity risk being reduced to power or self-interest.

As we step into this new year, soul-searching will ask uncomfortable questions of us as individuals, as families, and as nations. Are we building communities, or retreating into tribes? Are we demanding integrity from our leaders while excusing its absence in ourselves?

Sheptytsky believed that even in the darkest times, moral renewal was possible. This year, may we put our own house in order, and in doing so, help lay foundations of justice, mercy, humility and truth sturdy enough for the year ahead.

Jeff Fountain, Director of the Schuman Centre for European Studies. This article was first published on the author's blog, Weekly Word.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o