Arie de Pater, Brussels representative of the European Evangelical Alliance: “There is a tendency to call the migrant the problem, feeding a rhetoric in which we, Europeans, are the victims. But that is not the case”.

Seven-year-old Vahide holds her baby sister in their family home in Istanbul. / C UNHCR, Emrah Gurel

Seven-year-old Vahide holds her baby sister in their family home in Istanbul. / C UNHCR, Emrah Gurel

More than 43,000 people have arrived in Spain, Italy and Greece between January and June of this year.

European leaders are still very divided about how to address this complex humanitarian issue that continues to cause deep political debates.

Evangelical Focus asked Arie de Pater, the Brussels representative of the European Evangelical Alliance (EEA) to give a Christian perspective on the whole crisis, which he defines as a “moral” issue.

Arie de Pater, Brussels representative of the European Evangelical Alliance.

Arie de Pater, Brussels representative of the European Evangelical Alliance.Question. From what you’ve heard talking to Christians in Europe, what is the mood among evangelical Christians about the whole migrant and refugee crisis at this point?

Answer. Well, let me start by saying that there is a clear distinction between refugees and migrants. I’m always a bit concerned when I hear about the “refugee crisis”. That’s the term that is broadly used, but refugees themselves are not the crisis. It is a political and moral crisis more than a refugee crisis.

A migrant is someone who moved from one country to another voluntarily, so if you use the term “migrant”, that implies free choice. But a refugee is someone who is unable or unwilling to return to a country, because of a well-founded fear of being persecuted or other reasons, and they are entitled to international protection.

If a refugee comes to Europe, whether we like or not, we have to give them protection and to welcome them.

Q. Do you think other evangelical Christians in European countries have a similar approach to this complex issue?

A. We see a clear distinction between evangelicals who have met a refugee in person and those who are just absorbing the news like most of us, like everybody else.

For those who have met a refugee in person, it’s more natural to treat a refugee as a three dimensional human being, someone like you and me, created in the image of God, and therefore with infinite worth and dignity. For those people, it’s easier to reach out to refugees with compassion and Christian love, but for those who are just absorbing the news, it’s more of a challenge to see beyond just numbers.

Q. Leaders of EU countries had a key summit last week to better cooperate. The words “solidarity” and “responsibility” were heard once again. One of the agreements was to create a kind of “migrant processing centres”, where to decide if people arriving are refugees or economic migrants. The second agreement was to set up “regional disembarkation platforms” in Northern Africa. What is your reaction to these latest agreements?

A. To have controlled centres in Europe makes sense. It’s not a bad idea to have reception centres, where refugees are welcomed, where they are catted for, and where they have their basics needs met. They deserve a fair and efficient process to know whether they will be allowed to stay in Europe or whether they will be sent back.

The economic migrants – that’s up to the member states if they want to receive them or they need them, but they are not entitled to protection, so they can be sent back. If there is a decision not to accept them, there should be an efficient system to send them back to their countries of origin in a humane way. That is not necessarily a bad thing. We need to speed up the efficiency of procedures. I would love to see a common European approach to it, because now it’s up to the member states, so there is quite a diverse picture of who is accepted and who is not. That is a concern.

But we are more concerned about the vulnerable groups. Like refugees who converted along the way. They changed religion, converted to Christianity... They are particularly vulnerable, but that is not always clear to the officials dealing with the asylum applications. So, we’re seeing several countries in Europe that are repatriating people to Afghanistan, others are not.

I would have difficulties with everyone who declares Afghanistan a safe country. I think it would be helpful to have a common European policy that would set clear guidances about what is a safe country and what is not, who is a refugee and who is not. In that regard, the centres on European territory would be helpful, that wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing.

Outsourcing refugees to Northern African countries is more of a concern. I see the rationale behind it, because you don’t want see people drowning in the Mediterranean. But at the same time, it further dehumanises refugees: you reduce people to numbers and a problem.

There are legal and social problems that come with migration camps outside the EU, but it’s that general approach of saying: “We don’t want to see them, we want to keep them at a distance, and they’re just a number that needs to be controlled” - that worries me.

If we, as Europeans, dehumanise refugees and just see them as numbers, we are also dehumanising ourselves. Where is the compassion? Where is the solidarity? It is good to see these kind of words back in the European Council conclusions, but we have to see a return of these terms in a broader sense, in our European societies.

Q. You are dialoguing with other organisations in Brussels on this issue. What are some of the ideas heard there?

A. Most of the groups that we are working with in Brussels, are doing great projects in the countries where the refugees arrive. And they do good research in Northern Africa as well, in transit countries. It’s an interesting mix of very practical experience – they know what these reception centres look like, or what it means to receive people in the camps in Libya, or in Niger and other countries – and at the same time they are in Brussels, they know what is going on, what’s feasible in the political debate.

To strike the right balance is of course always a difficult question. On one hand you hear so many stories of refugees, that are just horrible; so you want to do everything you can to help them. And at the same time, we’re facing the political challenges, and nobody is immune to that.

We try to be explicit with the challenges that come with, for example, outsourcing refugees. We explore the legal and practical implications. And at the same time, we try to help officials to come up with constructive and realistic alternatives.

Q. You mentioned Libya and the sub-Saharan countries in Africa. Many say the solution is to solve the problems in the countries of origin. What can be done?

A. My concern is that with this rhetoric you easily forget that 85% of all the refugees are not coming to Europe, they’re hosted by developing countries. Countries like Niger, Mali, Libya, Ethiopia, but especially countries like Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan. They receive most of the refugees – at least percentagewise.

What comes to Europe is a small percentage. And initiatives to invest in Northern Africa with development aid is not a new phenomenon. We’ve been doing that for decades, and we have to continue to do that.

We have to invest in people, we have to invest in economic development and education. But not just as a tool to stem migration. But it is to help people to discover their strength, and to develop their God-given talents. We want Africa to flourish, and we want people to live a life in dignity as God intended them to live.

For he political issues, that we especially see in Syria, where there is a civil war, there are no easy solutions. But we have to invest in solutions for these problems.

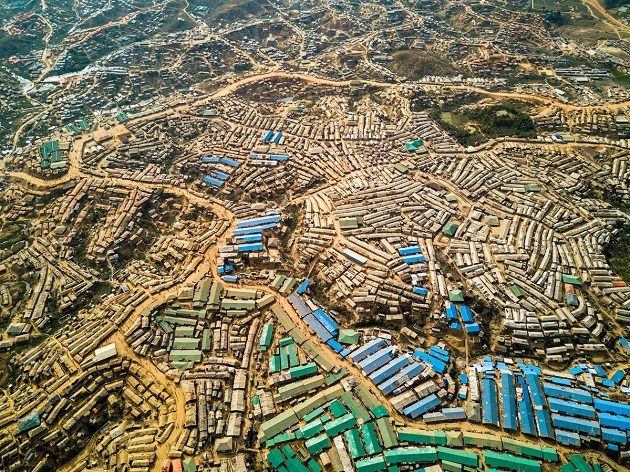

Bangladesh. Aerial View of Kutupalong Refugee Camp. / Photo: Copyright UNHCR, Roger Arnold.

Bangladesh. Aerial View of Kutupalong Refugee Camp. / Photo: Copyright UNHCR, Roger Arnold.Q. How should Christians have a prophetic voice on this issue?

A. For a Christian, I think it is important to continue to realise that this is about individuals. A refugee is a human being, just like you and me, created in the image of God. So, we have to respond to them with open hearts. Try to step in their shoes, nobody leaves their country just because... Well, it’s not a holiday! People are in desperate situations, and that’s why they leave their country. There’s always a story behind people leaving their country.

We have to be very cautious not to easily buy in to political rhetoric of the day. There is a political current that is just communicating on one-liners, providing simple answers to very complex issues.

I think it is the role of the church to ask the right questions, and to challenge those who use Christian terminology for their own political agenda. It’s the independent role of the church, of course to pray for people in authority and refugees, but also go back to the Bible, and ask: “What does the Bible say?”

Christian values of hospitality and solidarity are important guidelines for us in dealing with refugees. Where is the compassion in our societies?

People are in need to receive the safety that they need for them and their families, we need to help them to integrate in a country, a climate and a culture that is totally new to them.

Of course, we’re not naive. We are aware of the challenges and they need an answer. But talking about the prophetic voice of the church: let’s not reduce refugees to mere numbers and a problem that needs solving.

There is a tendency to call the migrant the problem, that feeds a rhetoric in which we, Europeans, are the victims. But of course, that is not the case. These refugees are victims of repressive regimes, of a civil war, of other catastrophes that have struck that country. We have to deal with them as human beings, and that’s the calling of the church, to be that prophetic voice in our societies.

Q. So, what can churches do on a local level, in the cities and towns where they are?

A. There are many churches that are reaching out to refugees. Once that a refugee has its application approved and gets permission to stay, it’s the role of the church to help them integrate.

You see many initiatives where churches are organising open activities to help refugees to learn the language, to understand the culture... And at the same time there are communities where they see refugees come to church, people who didn’t come to Europe as Christians. It’s great to see churches growing with refugees. It’s the compassion, and the very practical things that churches can do, but also the spiritual and pastoral care for people. They all come with their own stories, we have to help them to overcome and resettle in a new country.

Q. What would say to Christians in Europe ans elsewhere who support policies that criminalise migration and punish those who help migrants asylum seekers?

A. As I said, not everybody that comes to Europe is a refugee. We have to be careful, and we are well aware of the concerns and that we need sound solutions that make sense.

But a refugee is never illegal. If you flee a country, of course you have to cross a border to apply for asylum, you can’t apply for asylum im your own country. You have to leave your country to apply for asylum somewhere. If there are no legal ways of coming to Europe, they might cross the border illegally, but that does not make them and illegal migrant, because you need to cross the border to apply for asylum.

Of course, there are always people who use the opportunity and try to make money out of people in desperate situations – we hear about smugglers everywhere, and that’s terrible, and we need solid policies to stop that. But we shouldn’t hold our societies back from reaching out to people and give them a fair treatment, and an efficient and speedy procedure in Europe.

Q. Some Christians would say that the influx of migrants and refugees are leading Europe to lose its Christian identity.

A. I’m afraid the culture of Europe has already changed. As I said, to me, solidarity, compassion, hospitality are European values. But we already lost them in the political debate about numbers. So, our culture has already changed, and as churches, we have to go back to the Bible and say: “Is that correct?”

In the Bible there is a distinction. You have the alien or the sojourner, who usually came to Israel with no resources of him- or herself. They were dependant on the aid of Israel, and they were willing to integrate. They were always welcomed. But there was also another group, the foreigners who didn’t need any help, that were coming to Israel in their own initiative and were not really willing to integrate – and in the Old Testament there was a warning about these people.

So, there is an obligation of the refugees to integrate in our societies, but at the same time, there might be an even bigger responsibility on us to help them integrate, to welcome them, and to make room for them.

Q. We recently had Refugee Sunday in many evangelical churches in Europe and around the world. One of the special projects you at the EEA helped to produce is a film, “The Peace Between”. Tell us a bit about it.

A. It is always about human beings. With this film, we’re depicting friendships between a refugee and a European and the challenges and the advantages that come with that.

We realise that there is a difficulty to have a candid debate between people who are genuinely concerned about refugees, and people who are eager to welcome them. And sometimes you see these two positions combined in one person.

We hope that this film will really help people to step in the shoes of a refugee, and say: “Ok, what if I were a refugee, how would I feel? What would I need? What would I expect from the host community?” That’s why this is just a story about the friendships and how these developed.

As European Evangelical Alliance we drafted a discussion guide that helps people to wrestle with these questions, just like you and I did now over the last 20 minutes. We are all wrestling with the challenges that come with the influx of refugees. And we hope that, with this film and the conversation about refugees, we will help people to reflect on that.

Of course, we published this just before Refugee Sunday, but the film will continue to be available, and we still encourage people, also after summer, to have a look to the materials, to watch the film and see how they can use that in their own church groups or even in discussion with the wider society.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o