Embracing a theology of ‘unity in diversity’.

The story of how the early church expanded through Asia Minor and found a foothold in Europe is common knowledge.

However, the story of how it expanded on the opposite side of the Mediterranean through North Africa is less well known. At one point, the largest cities in the Roman empire were, besides Rome, Alexandria in Egypt and Carthage in present-day Tunisia.

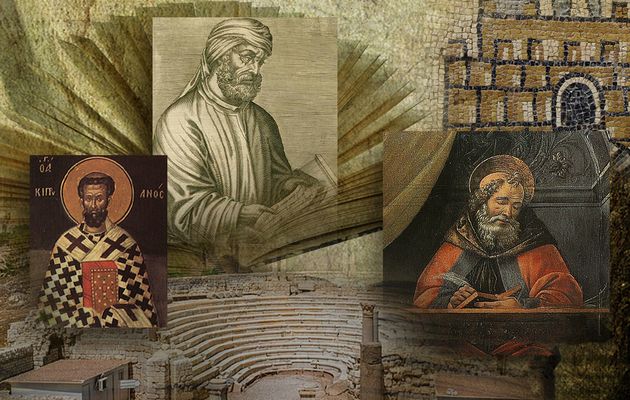

These cities also became strongholds for the Christian church. Early Christian thinkers, such as Tertullian, Cyprian, and Augustine, were all born in North Africa and served in Carthage.

With such a proud history, one might be puzzled by the outcome of the Arabic expansion in the region, from the seventh century onwards. Many scholars have battled with the question of why the church could not withstand the new masters.

There are several factors that might form part of the answer. However, we have singled out two that might also have something to teach us in our time:

We ask the question whether such dynamics may also throw light on contemporary church developments.

Augustine and donatists. / Lga.

Augustine and donatists. / Lga.

CONTEXTUALIZATION OR UNITY?

The Donatist movement, which gained a foothold among the Berbers, arose after Christianity became the official Roman religion. The Catholic Church remained politically and culturally faithful to the Roman empire, while the Donatist Church would represent a more nationalistic ecclesiastical movement.

It was shaped by the indigenous Berber community. It took a firm and conservative dogmatic stance, but incorporated a more charismatic form of expression. The Donatist Church took pride in its African heritage, Tertullian’s teaching on radical discipleship and the purity of Christian life, and its identity as a martyr church.

The Catholic Church, on the other hand, emphasized the universality of the church, Tertullian’s teaching on church unity, and its servanthood to society. It worked eagerly to adapt to a new status as the church of the Roman Empire.

The conflict between the Catholic and Donatist churches may thus be considered to represent the tension between the church as a global and a local entity, and the Donatists were considered a threat to the unity of the church.[1] It featured:

However, for present-day missionary work, we may ask whether unity needs to imply organizational unity and Christian cultural uniformity. Perhaps the missionary should rather encourage a ‘unity in diversity’,[2] where cultural characteristics are stimulated and not seen as a hindrance to Christian unity.

We should also pay greater attention to the Donatist Church’s history when we speak of the North African church—not the least because the Donatist Church remained in place in the face of the Muslim expansion, while the Catholic Church fled.

Further, we are tempted to imagine with L.R. Holme:

If the Church had only succeeded in getting hold of the great mass of the Berber tribes, if it could only have enlisted under the banner of Christ all the enthusiasm that afterwards supported the cause of Islam, it might well have been that not only would the Saracens have never succeeded in crushing African Christianity after the conquest of the province, but they might never have conquered the province at all. As it was, the teaching which appealed strongly to the Berber mind was condemned by the leaders of the Church as imperfect, and those who taught and believed it were subject to the ban of the ecclesiastical and secular authorities.[3]

Although it may sometimes be painful for those involved in missions when an indigenous church seeks separation and independence, or establishes practices that are unfamiliar and foreign, yet, the modern missionary should ask whether the church is simply coming of age.

Christian berber family from Kabylia.

Christian berber family from Kabylia.

CHURCH BETWEEN CULTURAL CENTER AND PERIPHERY

The Berbers were traditionally nomadic and remained largely a rural group. They were never tempted by the culture of the cities, which was strongly influenced, and dominated by the Roman immigrants and their cultural heritage.

Berber societies were organised according to tribal structures, inherently opposing the Roman-controlled, centralized state.

Over the centuries, the cities in North Africa increasingly became administrative centers, populated by the political, financial, military, and religious elite. The Catholic Church, Latin language, and the Roman way of living dominated in every aspect.

Thus, the Berbers, although representing the indigenous population and constituting the ethnic majority, remained culturally peripheral, lacking influence as well as political, financial, and cultural representation.

Several studies have demonstrated how religious conversion and the religious development of various groups have often been interrelated with greater socio-political and ethno-political dynamics, and, accordingly, must be interpreted through such frameworks.[4]

Experiences of ethnic and cultural marginalisation may play a significant role in strengthening the ethnic identity of a group, in opposition to the dominator.

The history of the Berber population in North Africa follows a recognizable pattern in this regard. When the Roman occupying power discouraged and persecuted Christians during the first three centuries, surprisingly, Christianity found a foothold and thrived among the Berber population.

Later, after the Catholic Church became the religion of the state from the year AD 380, the Berbers turned from the Catholic Church to Donatism, and persecution continued. Thus, religious following and religious identity continued to constitute an element of opposition to foreign rulers in the area throughout this considerable timespan.

A similar pattern has been identified in various other contexts, including in modern times. One such example is the history of religious development in parts of Eastern Africa. Several studies have demonstrated how opposition to the historically dominant group, the Orthodox Christian Amhara people, played a significant part in forming the religious fabric of present-day Ethiopia[5]:

Although greater socio-political and ethno-political dynamics may be influencing religious change, and also conversion to Christianity, this does not necessarily imply that individual conversions are not genuine.

It simply underlines the fact that religious reorientation does not take place in a vacuum. None of us are unaffected by the culture and society to which we belong.

Furthermore, it may indicate that God is at work in shifting conditions, and that God relates to us as people of cultures and societies. It is therefore interesting to note that a similar dynamic may be taking place in the North African region at present:

FURTHER LESSONS FOR THE CONTEMPORARY CHURCH

Every cross-cultural missionary brings with him or her a heritage, regarding both theology and culture. Often the two may be difficult to distinguish, since religion is also an integral part of culture.

Accordingly, no missionary is culturally unbiased, and our gospel message tends to carry cultural predispositions. There is no difference in this regard, whether our theological and cultural heritage is Korean, Nigerian, or Norwegian.

A simple reproduction of our church heritage in other cultures may well become an ‘ecclesiological imperialism’, where we, perhaps unwittingly, impose our tradition on others. We should rather ask ourselves what part of our message is indispensable, and what is not.

Cross-cultural missionaries also need to consider the aspects of political, financial, and power representation. Being cultural outsiders, there is no ‘neutral space’. We always represent something.

Although we may not be able to remove such representation, the missionary should be attentive to it, and seek to counteract the influence of such elements. Otherwise we may contribute to alienating the church from its context.

The trailblazer of twentieth-century missiology, Paul Hiebert, championed the importance of ‘self-theologizing’.[8] Every young church needs to develop a contextual theology, one that makes cultural sense and gives answers to questions of cultural relevance.

Missionaries should encourage such a development, even if the local leaders may not always reach the same conclusions as would the missionary. This may be a painful process, as the history of the Berber church has emphasized.

However, it may also be a process of growth for the missionary, as our church heritage is challenged and may develop further in dialogue with new perspectives.

Churches worldwide might gain from embracing a ‘unity in diversity’. In the contemporary Western world, this challenge is just as valid with regard to emerging immigrant churches in their midst.

The ‘majority churches’ of the West must consider how they can relate to the new immigrant churches in such a manner that the influx of Christians from the Global South may make a positive contribution towards reinvigorating and reinterpreting Christianity in the West.[9]

Mons Gunnar Selstø works with the Norwegian Lutheran Mission. He has served as a missionary among Muslims in Mali and is currently working in cross-cultural ministry among immigrants to Norway.

He wrote his thesis for his masters degree in theology and missions on the history of the church in North Africa.

Frank-Ole Thoresen is President of Fjellhaug International University College. He has served with the Norwegian Lutheran Mission and the Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus, mainly working among Muslim peoples in East Africa.

He has done research on contextual ecclesiology among persecuted Christians in East Africa. Frank-Ole received his PhD in Theology from VID—School of Mission and Theology.

This article originally appeared in the September 2018 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis and is published here with permission as part of the LGA Media Partnership. Learn more about this flagship publication from the Lausanne Movement at www.lausanne.org/lga.

Endnotes

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o