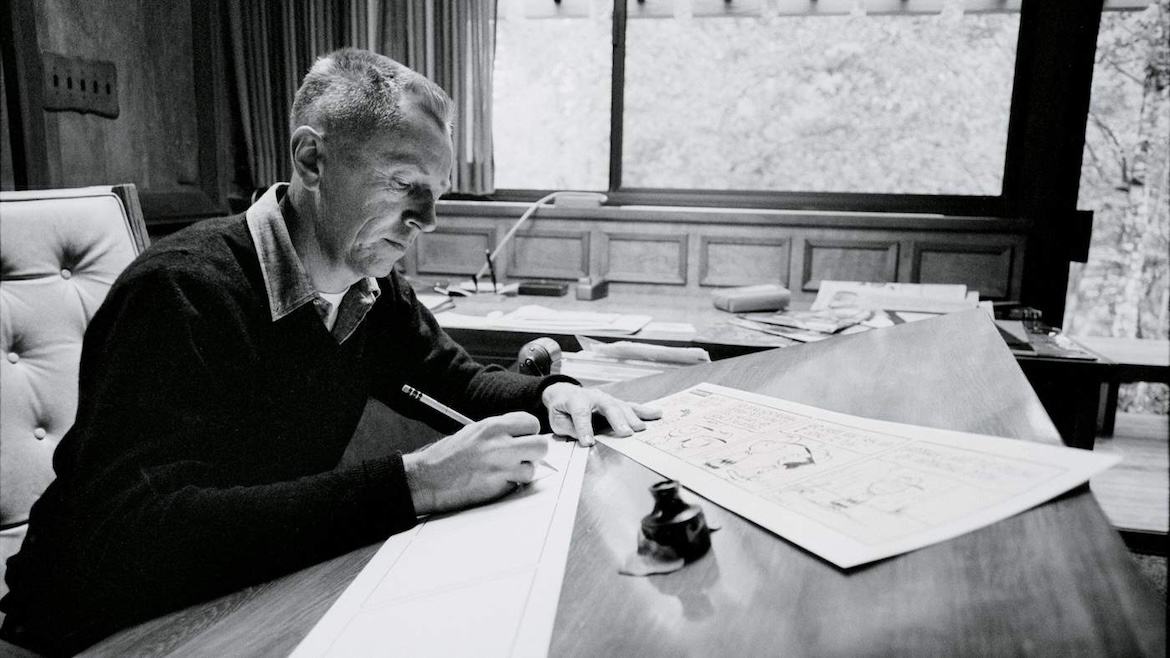

Snoopy has become a popular culture icon. His author, Charles Schulz (1922-2000) had an interesting relationship with evangelical faith.

It is the 75th anniversary of the Peanuts comics trip (1957–2000). Snoopy, one of the characters, has become a popular culture icon. His author (1922–2000) had an interesting relationship with evangelical faith.

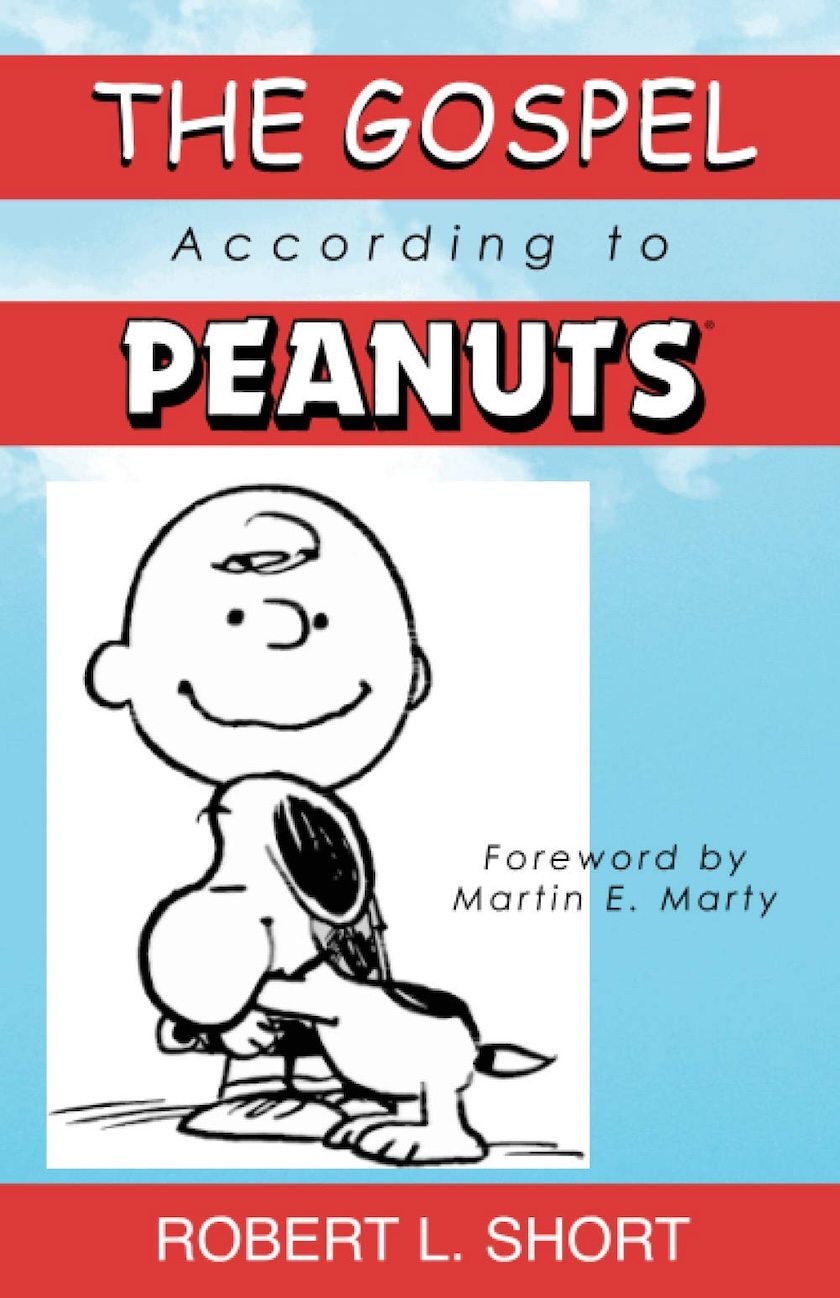

In the United States, ever since the publication of the classic The Gospel according to Peanuts by the Presbyterian pastor Robert Short in 1965, until the latest book of its kind, The Charlie Brown Religion: Exploring the Spiritual Life and Work of Charles Schulz (2015), by Stephen Lind, there has been an interest in the subtle influence of Schulz’ Christianity on his stories.

Despite being as American as Elvis or Marilyn, the characters of Snoopy and Charlie Brown have become well known household names worldwide. Less is known about the influence of the Bible, prayer, God’s nature and the end of the world in this comics. Our approach to this question is not thematic but rather narrative, following the course of Schulz’s life. Around 560 of the 17,800 published comic strips have religious, spiritual or theological references, and they all relate to the author’s life.

[photo_footer]In 1965, the Presbyterian pastor Robert Short published The Gospel according to Peanuts, the first book on popular culture of its kind.[/photo_footer]

The success of his first TV programme about the "True meaning of Christmas" in 1965, in which Linus recites the text of Luke’s Gospel in the classic King James’ version, is just one example of the importance of Christianity throughout Schulz’s work. He was raised in a Lutheran family but, after the Second World War, experienced an evangelical conversion in the Church of God in Anderson (Indiana), which follows in the holiness tradition.

The author of Snoopy and Charlie Brown became an insatiable reader of theological commentaries. The margins of his Bible were crammed full with handwritten notes. He later became a Methodist and taught at Sunday schools in the Mid-West and California. He even led an Old Testament study group.

At the end of the 80s he had a crisis of faith after which he declared himself a “secular humanist”. He was a complex person, as we will see in this series but, according to his widow, “he was a deeply thoughtful and spiritual man”, who never stopped thinking about God.

Schulz was always a solitary person. Following his mother’s death, he started going to the youth group of the local Church of God, which he attended three times a week, for the service and two bible studies. He read the Bible through several times and always tried to understand exactly how to interpret what he read. As a result, he ended up teaching Scripture for a number of years.

However, according to his widow, “When he taught Sunday school, he would never tell people what to believe. God was very important to him, but in a very deep way, in a very mysterious way”.

[photo_footer]Snoopy was so well known that his image was ubiquitous – even making it into the “Space Race”.[/photo_footer]

Everyone that knew Schulz remembers him as someone “difficult to get to know and understand”. Even those who considered themselves his friends would say that “he did not want to get too close to anyone”. Others say that “he considered himself a simple person, but also enigmatic and complex”. The most common adjective used to describe him, apart from “shy and humble”, is “complicated”. For someone so reserved, it is surprising how much of his life he reflected in his comic strips and how many interviews he gave, speaking in detail and frankly about many subjects.

His work is so personal to him that he drew every single one of his comic strips without any assistants. If he had been more sociable, he probably would not have been able to create the suffering and indomitable Charlie Brown, the bad-tempered and poisonous Lucy, the dreamy and reflexive Linus, the stubborn Schroeder and the pensive Snoopy.

The famous dog was based on his childhood dog, Spike, but he never said who his inspiration was for Charlie Brown and Lucy. His characters may have all been a reflection of himself, having once said that characters could only be created from one’s own personality and not by observing others.

[photo_footer]The famous Snoopy dog is based on his childhood dog, Spike.[/photo_footer] Born over a century ago in the deep Mid-West, he was the only son of a barber from St Paul (Minnesota) and a kind, loving homemaker. He would say that his only ambition was to be as appreciate as his father, but when he was invited to talk about his life he would never start with his early years but with the death of his mother. It is no coincidence that his Christian conversion happened after her passing, when the pastor at her church – a Church of God in Anderson (Indiana) – asked Schulz to help him prepare her memorial service. After speaking with his father, the pastor invited him to come to the church, which came to take a central place in his life for the next four or five years.

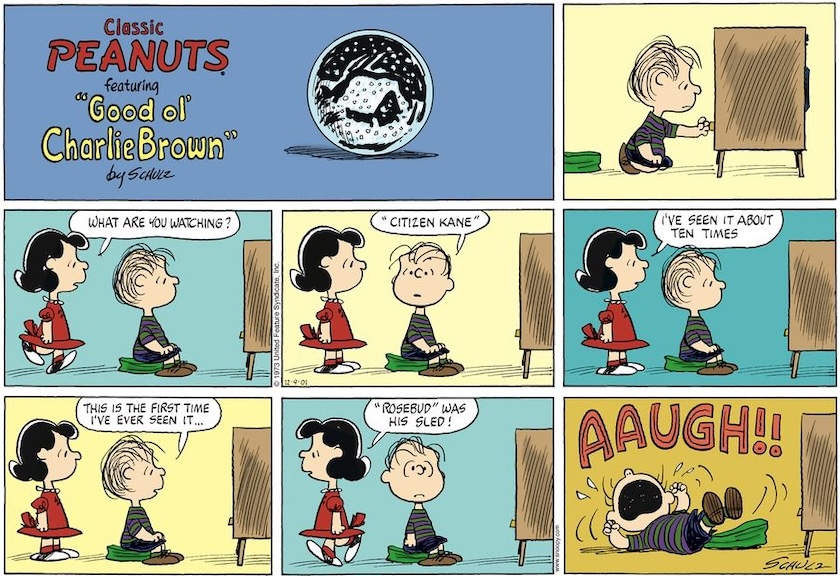

In 1941 the film “Citizen Kane” by Orson Welles was shown at the cinema in St Paul. Schulz’ fascination for this masterpiece – voted the best film in history, year after year, by film critics the world over, until it was unseated by Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” – became a real obsession. He saw it some forty times. Schulz found many parallels to himself in the story of a discreet and powerful man, an only son, thrown out of his cabin in the middle of the snow, educated by a banker and ending up in an isolated castle in Xanadu.

The enigma of the word “Rosebud” in “Citizen Kane” is also the key in this series about Schulz’s mysterious faith. I don’t think that I am giving the film away if I say that Kane’s name for his childhood sledge – despite the sexual meaning that it had for the publishing magnate that inspires the character, William Hearst – presents us with a man who, like Schulz, “achieved everything he desired and then lost it”. Like Kane, he felt alone all his life, wishing for the care and understanding of the mother that he had lost.

[photo_footer]The enigma of the word “Rosebud” in “Citizen Kane” is also the key in this series about Schulz’s mysterious faith.[/photo_footer] He never discussed what kind of cancer that took his mother. Most of his family thought that it was colon cancer, but it was actually uterine cancer. She started suffering from it in 1938. When Sparky – as Schulz was nicknamed – came home from school, he would find his mother, Dena Schulz, lying in bed. No one spoke about her illness. Only his father and his aunt knew about it. It wasn’t until she reached the fourth and final stage that they decided to tell Sparky, the same month he was called up in 1942. The following year he was on leave when he came home from Fort Snelling to be by his mother’s bedside.

Before going back to his barracks, he told his mother that he was leaving. She replied: “Yes, I suppose that we should say goodbye”. Looking at him, she said: “Bye then, Sparky, we probably won’t see each other again”. Until the day he died, he never got over that moment. It was his greatest tragedy.

She never saw his work. Throughout his life, Sparky sought that maternal love but, like his characters, he felt that he only encountered indifference and rejection. It made him appear not only cold, remote and elusive, but also insensitive, mocking and scornful. He was so close to his mother that until he joined the Army, he had only spent two nights away from her when he had participated in a golfing tournament when he was 18 years old.

He didn’t have a girlfriend. His only dates were with the daughters of family friends. He didn’t want to travel, even to see the sea. He would never stay in hotels or go out to restaurants. He would just retire to a quiet place to draw. He survived the war, but never saw his mother again.

[photo_footer]Throughout his life, Sparky sought that maternal love but, like his characters, he felt that he only encountered indifference and rejection.[/photo_footer]

In this life we all have emotional wounds, lost loves and absences that no one can fill. They are “bonds” that limit us and stop us enjoying life. Whatever “bonds” you have in your life – a habit you can’t shake, sin, a feeling of failure or past mistakes – in its very first pages, the Bible presents us with Someone who had no “bonds” or limitations. The God we find there (Genesis 1 :1) does not have a beginning or an end. The only time he bound himself to time and space was when he came down to Earth to be one of us, subject to time and space.

God experienced the rejection and incomprehension that many of us have felt, but on a scale that we can never imagine. Nailed to that Roman cross, he was abandoned by everyone, even his eternal Father (Matthew 27:46), so that we should never have to be. His suffering subsumed all our infirmities, all our wounds and he carried all our sin. Why did the eternal God wish to bind himself to such suffering? Because he loves us so much that he wants to free us from our “bonds”.

In the power of his resurrection, he can cure our illnesses, repair what has been broken and find what has been lost. When we doubt that this is possible, we should think of that Cross, because in it we find that Love that seems to have fallen away from us forever. Contemplating that sacrificial lamb (Revelation 5 :12), we will be filled with wonder, because that which appeared too good to be true, will become reality for all eternity.

[analysis]

[title]Join us to make EF sustainable[/title]

[photo][/photo]

[text]At Evangelical Focus, we have a sustainability challenge ahead. We invite you to join those across Europe and beyond who are committed with our mission. Together, we will ensure the continuity of Evangelical Focus and our Spanish partner Protestante Digital in 2025.

Learn all about our #TogetherInThisMission initiative here (English).

[/text][/analysis]

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o