Biblical archaeology does not seek to prove or disprove the content of the Bible, but to describe the historical framework in which the biblical books were formed.

Archaeologist Tim López Eriksson during his conference on biblical archaeology.

Archaeologist Tim López Eriksson during his conference on biblical archaeology.

On Saturday 24 October 2020, the United Christian Church of Valls (ECUV) in Tarragona, Spain, held a conference on biblical archaeology.

The speaker was the archaeologist Tim López Eriksson, who has studied Classical Archaeology and Ancient History at the University of Upsala (Sweden) and has a Master's degree in Classical Archaeology from the Universitat Rovira i Virgili in Tarragona.

He has participated in archaeological excavations in Spain, Egypt and since 2017 in Shiloh (Israel) with Associates for Biblical Research.

López began explaining that today biblical archaeology does not seek to prove or disprove the content of the Bible, but to describe the historical framework where the biblical books were formed, focusing on the Middle East, especially the area of Israel, Jordan, Syria and Egypt.

The Bible is very present in this branch of archaeology, and there are two very opposite lines of thought, depending on how the biblical texts are treated in relation to archaeological material: minimalism and maximalism.

Maximalism would be the traditional one, which accepts the biblical account as a reliable historical source. Minimalism sees the biblical text as an invention after the historical events, to recreate a glorious past that would be fictitious.

Most of the academic world now supports the minimalist vision. An example would be the belief that the United Monarchy (David and Solomon) or the Exodus out of Egypt, never happened.

But archaeology has already confirmed many of the facts that appear in the biblical text, and López said he was convinced that more findings that follow the biblical line will be unearthed.

López presented two objects recovered in archaeological excavations in Jerusalem, as an example of the fact that there is archaeological confirmation of more than 50 characters mentioned in the Bible.

The first was a clay print of King Hezekiah's seal. The inscription reads 'Of Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz, King of Judah'.

The second example was also a clay print, that may have belonged to the prophet Isaiah. Those who studied and published this piece made a reconstruction by adding two letters in the first line, and one in the second. If this reconstruction is correct, the seal says "from Isaiah the prophet".

López explained how some of the most important archaeological discoveries have, in one way or another, confirmed the biblical story.

Among the most known discoveries are the Dead Sea scrolls, a collection of manuscripts consisting of more than 25,000 fragments of parchment and papyrus that were found in 1947 in the caves of Qumran, West Bank.

Most of the fragments date from 250 BC to 66 AD. These are Jewish religious texts, with the oldest copies of the Bible.

Before the Dead Sea scrolls, the oldest complete copy of the Old Testament was the Leningrad Codex, dating from 1008 AD. A comparison between both findings was made, to determine how much the text had changed in 1,000 years.

The results showed that very little had changed and that the text of the Leningrad Codex was virtually identical to the equivalent texts of the Dead Sea scrolls.

Prior to the discovery of the Dead Sea scrolls, the academic world criticised Jesus' life as the Messiah and his fulfilment of the prophecies mentioned in the Old Testament, especially those of Isaiah.

The fulfillment by Jesus Christ was so accurate that the prophecies, according to this criticism, had to be edited after Jesus' death.

But a scroll appeared among all the fragments of Qumran, which experts managed to date back to 100 BC. It contained the complete text of the book of Isaiah.

The question of whether or not Jesus was the Messiah remains a question of faith, but that manuscript made it clear that the prophecies about the Messiah were already written before Jesus' life.

The Tel Dan Stele is a stele with an inscription in Aramaic that was discovered in the 1990s at the Tel Dan site.

It dates to the 9th century BC and the inscription tells how an individual (the name is not mentioned, but probably Hazael) killed Joram, the son of Ahab, King of Israel and King of the 'House of David'. This inscription corroborates the biblical account of 2 Kings chapter 3.

This is the first and oldest mention of King David outside the Bible. This finding significantly weakens the minimalist position that King David never existed.

The Stele of Merneptah is a 3-metre-high slab of black granite that describes the military victories of Pharaoh Merneptah around 1210 BC and contains the oldest mention of Israel outside the Bible.

The people mentioned in the stele are called foreign land, but Israel is mentioned in a different way, it is referred to as "the people of Israel", showing that, for the Egyptians of that time, Israel was considered a foreign group.

The fact that Merneptah boasted of his victory over Israel implies that the Israelites were already a strong enough people established in the area of Canaan in the 13th century BC.

Ketef Hinnom's amulets were found on tombs in Jerusalem in 1979. They were tiny silver rolls. It is one of the oldest and best preserved inscriptions that contains the name of the Israelite God: YHWH.

The style of the tombs and the writing used in the inscriptions allowed them to be dated to the 7th or 6th century BC, making them the oldest known copy of a Bible fragment.

During the conference López also detailed how he discovered a small ceramic figure representing a pomegranate in Shiloh, which appeared in several of the lists of the most important finds of 2018.

Siloh is the place where the young Samuel was brought up under the custody of Eli. The story can be read in the first chapters of 1 Samuel, but Shiloh is also mentioned several times in the books of Joshua and Judges.

It was there where the Israelites gathered after the Exodus, to divide the Promised Land among themselves, and the Ark and the Tabernacle remained there for over 300 years until the time of Samuel.

The day it was discovered, a group of about 30 students from DTS (Dallas Theological Seminary) was visiting the site to work as volunteers, and López could assign 6 students to his team, to work in the L.7 stratum.

After a while, he noticed that many baskets were piling up in the screening area, so that they were running out of empty baskets, and he decided to come over to help them screen the material from two baskets.

He could immediately see a different object, but he did not have time to examine it thoroughly, so he put it in his right pocket and went back to work.

About 15 minutes later, he remembered the piece in his pocket and started to study it. It was a figure about 4 cm long and almost 3 cm wide. At the top there was a horizontal hole to hang the piece, and at the bottom something that seems like "petals".

Along with the director of excavations Scott Stripling and other specialists, they determined that the figure was probably part of an incense burner similar to the one at Tel Hatzeva, and that it dated to the Iron Age (probably 9th-10th century BC), although someone suggested that it might have been part of the high priest's clothing, according to Exodus 28:33.

In July 2019 news appeared of an important discovery that Lopez's team had made that same year at the excavations in Tel Shiloh.

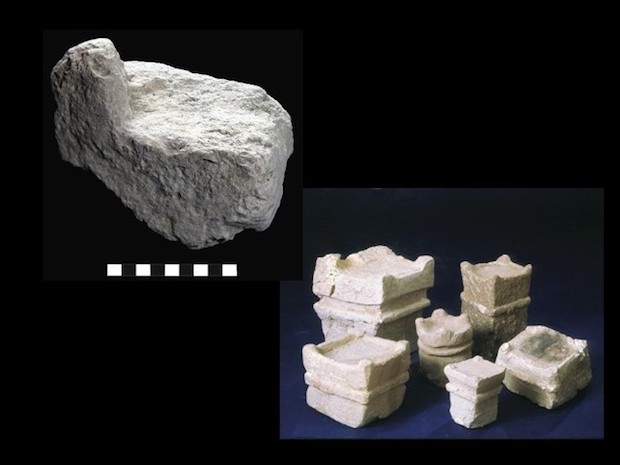

It consisted of a piece of stone measuring 18 x 12.5 centimetres, which was finally determined to be the corner of an altar with one of the four typical horns that would be located at each corner of the entire altar.

The fragment appeared in one of the spaces Tim was supervising. The discovery was important, not only because it is a religious object, but also because of the place where it was found.

Although this object itself cannot confirm that the Tabernacle was actually in what is now known as the site of Tel Shiloh, it does indicate that there was religious activity there.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o