His father was a fairly liberal reformed pastor. He spoke of Christ more as an example, than a substitute for sinners.

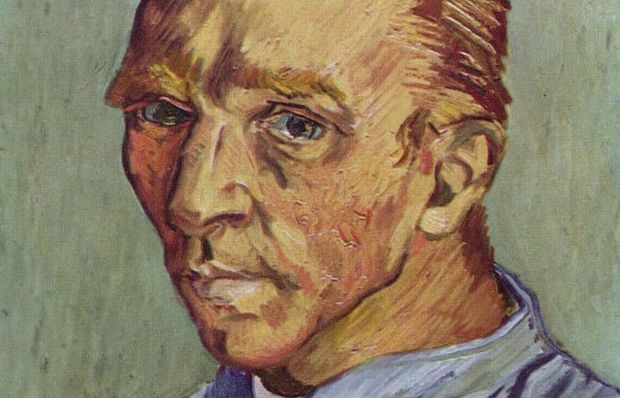

In his last self-portrait, Van Gogh appears without his beard

In his last self-portrait, Van Gogh appears without his beard

It is now 125 years since Van Gogh (1853 –1890) shot himself in the chest as he looked out onto a corn field in the small village of Auvers-sur-Oise (France). This son of a Protestant pastor professed his Christian faith in the Dutch Reformed church, feeling a spiritual vocation which led him to work as a preacher among Belgian coal miners. An exhibition in the small hilly town of Mons – the current European capital of culture – provides an overview of his artistic work during the time of his ministry, which ended in deep crisis…what happened to his faith?

Van Gogh entered into the “long night”, which Paul Klee called his “exemplary tragedy”. The cult to his genius and his madness have made many people today see his art as the result of a “martyrdom” which they associate with his Protestant education. They argue that his first years were marked by a “dark light”, but what was the Calvinist environment in which he grew up really like? Many people imagine that it was characterized by the strict discipline of a fundamentalist faith, but the truth is that his father was a fairly liberal Reformed pastor. He spoke of Christ more as an example than a substitute for sinners. In reality, his father had substituted evangelical theology with suffocating moralism.

Orthodox Calvinism has always believed that man cannot abide by God’s Law on his own, whereby our life depends entirely on Christ’s obedience in our stead. The gospel that Van Gogh’s father preached was more about the imitation of Christ, which has been the great attraction of Roman-Catholicism. The difference is not a question of nuances. What is at stake is the huge abyss dividing God’s grace and evangelical moralism. For Van Gogh, Christianity consisted in a love which, though awoken in us by Christ, needed to be achieved at all costs. It is no wonder that Van Gogh felt that he had never managed to live up to his father’s expectations. Such a faith highlights all our faults and contradictions, but brings no good news.

PREACHER OF LOVE

Contrary to many other artists, Van Gogh read and wrote a lot. One of his favourite books was “The Life of Jesus” by Renan (1863). This French author describes Christ as a sensitive idealist, an ethical genius, who like a tragic hero provides inspiration through the nobility of his acts. Van Gogh procured this book when he was in London in 1875, and he quoted it extensively in his letters to his bother Theo. At that time his romantic ideas sought “love for the sake of love”, in the impossible universal task of “ending with the banality of human life”. That was why he decided to become a preacher…

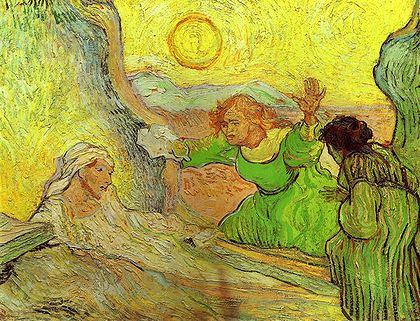

Van Gogh painted this paint when he was an evangelist in the mining area of Borinage, between France and Belgium.

Van Gogh painted this paint when he was an evangelist in the mining area of Borinage, between France and Belgium.As he prepared to study theology in Amsterdam in 1877 and 1878, his introduction to Greek and Latin was accompanied by exercises in asceticism. And as a new Saint Francis, when Van Gogh eventually went as a missionary to the Borinage – a mining area between France and Belgium –.he shared his possessions with the miners. His radicalism resulted in crisis, causing him to give up his ministry and dedicate himself to art with the same fervour. “Painting is a faith”, he wrote to his brother Theo, in his 493rd letter.

He began to preach through his images, as seen in his painting after the death of his father. It shows a large Bible, which he inherited, open at Isaiah 53, which announces the suffering servant of God. All the space surrounding the Bible is dark; the only candle which could provide some light is out. What is illuminated is the cover of a very used book “The Joy of Living” by Emile Zola. The title of this book is deceptive in that it is really about the misery of life. What was he trying to say with this? For him, the misery of daily life allows us to reflect the image of the suffering servant. The Bible thus stands as an example, which we can understand better in the light of Zola, than in the light of any other pious author. It is the Christ of Renan, and not of the gospels!

VAN GOGH’S CHRIST

Van Gogh thus identifies Christ with any girl that he meets in a cafe, as he does in his personal interpretation of “Ecce Homo” (letter 533), and the artist thus sets out on his own personal Gethsemane, passing by olive trees, cypress trees and fields alight with corn. It is as if through him, all the earth, nature and the cosmos, presents itself in unison to the “man of suffering”. His yellows express terror, but also consolation. That sunlight thus becomes the symbol of communion with a cosmic love. That is why in “The Rising of Lazarus”, his painting based on a sketch by Rembrandt, Christ is substituted by the sunlight. It is not about using symbols from nature as in primitive Christianity, about bringing the light of eternity to a subjective nature. Art thus becomes religion.

Van Gogh substituted Christ for the sun.

Van Gogh substituted Christ for the sun. For Van Gogh, Christ is the supreme artist, “since he makes living people immortal” (letters 635–636). And until the end, Jesus continued to be an example for him in his mission as an artist. But he was no more than that; an example in a life without God, seeking salvation through his own means, “through pain to glory”. Although he was generally misunderstood, Van Gogh always believed in his art, which he saw as a gospel to humanity: “consolation for future generations”. It is that confusion that led him to write in one of his last letters before committing suicide that he saw himself “as a bonze, a simple worshipper of the eternal Buddha” (701). But even when he spoke using Christian discourse, his faith went no further than a faith in himself.

LIVING AS GODS

And this is how many of us wish to live, through our own creative capacities, like Gods, creating our own truth in our own personal “reborn universe”. We try to live and die creating our own existence, even though this only leads to an eternal destruction. And might such Gods not sometimes require human sacrifices? Yes, for example, on losing one’s creative capacity. Suicide thus becomes a last creative act. That is Van Gogh’s tragedy, but it is anything but exemplary. That is why his gaze shows the passion of devastation, fear of the void which causes him to say: “When I have a terrible need of - shall I say the word - religion. Then I go out and paint the stars.”…

I don’t know whether Van Gogh discovered that there is Someone beyond the stars, who understands and loves us, not because of what we do, but because of what Jesus has done for us. Hidden behind that sun of justice, we can live in the light. But if we only trust in ourselves, rather than in his life and warmth, we will be exposed to his blinding light and live in terrible darkness. We are afraid of exposing ourselves to a light which shows everything up, but there is no greater consolation than finding refuge in the shadow of the Son of Light.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o