What did the “Lordship” of Jesus mean for first century Christians?

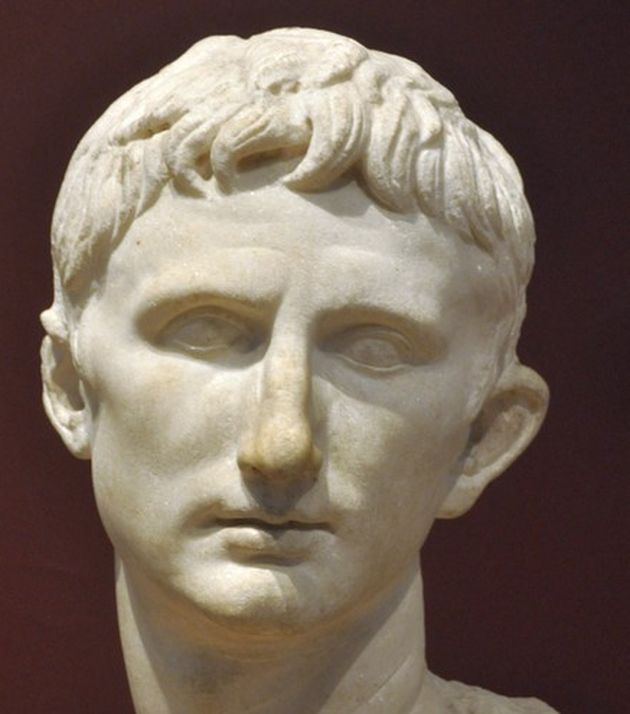

Augustus. Istanbul Archaeology Museum. / Livius.org

Augustus. Istanbul Archaeology Museum. / Livius.org

What does it mean for Jesus to be “Lord” and “Savior”? Why is the coming of Jesus “good news”?

Often times when we read these terms and we interpret them conveniently with “us” at the center of the message. “Jesus died for me” “Jesus saved me”. But what did these words mean for first century Christians? What did the “Lordship” of Jesus mean for them?

Roman Emperors during the lifetime of Jesus

Two of the Emperors that lived during Jesus’ lifetime are Augustus and Tiberius. Augustus’ name was Gaius Octavius Thurinus. This title ‘Augustus’ means “majesty” or “venerable” and it was first given to him by the Senate in 27 BCE. Augustus was born in 63 BCE.

He took over power from Julius Caesar but before could gain the throne, he was forced to battle the armies of both Cleopatra VII and Marc Antony. Augustus was the emperor that reigned during the birth of Christ.

According to Luke, he was also responsible for a census (Luke 2:1). Augustus dramatically enlarged the Empire. Due to his extensive building projects and revenue reforms, many consider Augustus to be Rome's greatest emperor. His policies initiated the celebrated Pax Romana or Pax Augusta.

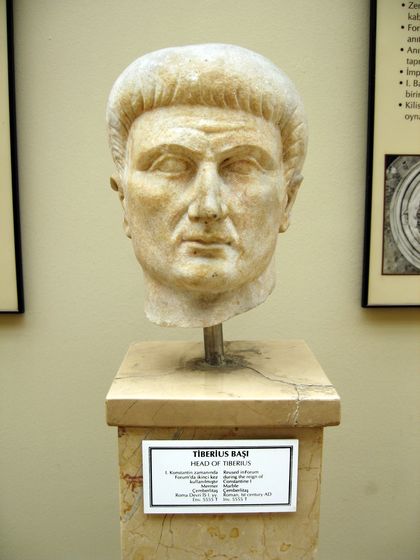

Tiberius was born in 42 BCE. He reigned from 14 AD to 37 AD. He was the Emperor during Jesus’s ministry on earth. He appointed Pontius Pilate who would adjudicate the crucifixion of Jesus.

He was a great general and left the Roman treasury at a surplus. However, starting in 23 AD after the death of his son he became reclusive and distanced himself from his responsibilities which made many historians remember him in a negative light.

The Emperor Cult and the Cult of Christ

“These men who have turned the world upside down have come here also, and Jason has received them, and they are all acting against the decrees of Caesar, saying that there is another king, Jesus” (Acts 17:6-7).

Modern readers of the Bible tend to overlook the polemic nature of the Christian message in the first century. Paul and his friends were accused of recognizing only one king: Jesus.

To Paul’s hearers, his message of allegiance to one king only meant that the Emperor was delegitimized. It would amount to treason.

In the first century many of the titles used by Jesus and even the word gospel (good news) was used in the context of Emperor worship.

In a two-part inscription found in the ancient city of Priene in western Turkey dating from 9 BCE and now stored in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, The birth and appearance of Augustus Caesar were heralded as “good news”.

The emperor was celebrated “in practical terms at least, in that he restored order when everything was disintegrating and falling into chaos and gave a new look to the whole world, a world which would have met destruction with the utmost pleasure if Caesar had not been born as a common blessing to all”.

The decree in this inscription states that the Greeks in Asia decided to celebrate new years on September 23rd in honor of Augustus’ birthday. Notice the language and especially the title used to describe the coming and appearing of Augustus:

“Since the providence that has divinely ordered our existence has applied her energy and zeal and has brought to life the most perfect good in Augustus, whom she filled with virtues for the benefit of mankind, bestowing him upon us and our descendants as a savior—he who put an end to war and will order peace, Caesar, who by his epiphany exceeded the hopes of those who prophesied good tidings (euaggelia), not only outdoing benefactors of the past, but also allowing no hope of greater benefactions in the future; and since the birthday of the god first brought to the world the good tidings (euaggelia) residing in him . . . For that reason, with good fortune and safety, the Greeks of Asia have decided that the New Year in all the cities should begin on 23rd September, the birthday of Augustus”.

Augustus is the savior, the god, the prophesied one. Though not found in this particular inscription, we do know from other records that Augustus was also called lord and “son of a god” (Lat. divi filius).

Divi filius was an especially useful title used as a propaganda tool against his political rivals and numerous coins minted during his reign bear that title on them. Later on emperors like Tiberius, Nero and Domitian would also adopt these titles.

Tiberius. Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

Tiberius. Istanbul Archaeology Museum. The term good news too was also not exclusively used for the birth of Augustus. A gospel would especially be heard especially after important victories in Battle. Messengers would be sent to various cities to announce the good news of the defeat of the enemies and the victory of the Emperor.

Imagine for a minute the impact of the introduction found in the Gospel according to Mark. A gospel, which according to Papias, was written for the church in Rome during the reign of Nero as a compilation of Peter’s sermons concerning Jesus Christ: “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” (Mark 1:1).

It seems that Christians did not shy away from using polemical language nor were they interested in softening their tone. The gospel, in this respect, was an open challenge to the Roman conception of Emperor divinity.

In chapters 1-5 we see a Christ who has power over illness, evil spirits, and nature. In chapters 11-16 We see a Christ who challenges the established temple authority, the religious leaders, cleanses the temple, and ultimately defeats death.

In chapters 6-10 of we have the 3 conversations between Jesus and his disciples where he challenges them to be loyal to him alone: “take up your cross and follow me”.

This non-negotiable attitude and message are what eventually brought early Christians much persecution. It’s possible that part of their audacity can be explained by the fact that at its early stages Christianity was seen as a subset of Judaism.

Jews had special treaties with the Romans allowing them monotheistic worship and exempting them from sacrifices. However, as Christians started to be excluded from the synagogues its conceivable that attitudes changed rather drastically.

Roman persecution was not only physical but in many cases psychological. Though there are instances of serious systematic persecution, most of the cases seem to have been sporadic, spontaneous and regional in their variety.

Revelation was written to the churches in Asia which suffered from one of these waves of persecution probably during the reign of Domitian (though there are those who defend an earlier authorship).

Of special interest is John’s usage of the phrase “the Lord’s day” (1:10). This phrase is traditionally understood to mean Sunday. However, throughout the New Testament Sunday is consistently referred to as “the first day of the week” (Matthew 28:1; Mark 16:2 2, 9; Luke 24:1; John 20:1, 19; Acts 20:7; 1.Corinthians 16:2).

Another possibility is that it may be a reference to “the day of the Lord” that is, a reference to the day of judgment when Christ will judge the nations.

However, the presence of the adjective kuriakos makes the expression grammatically different from the common biblical phrase "the Day of the Lord," which uses the genitive form of the noun kurios.

According to Renner: “The phrase ‘the Lord’s day’ is a translation of the Greek word kuriakos, a specific word that was used primarily to describe the Emperor’s Day.

It has been proven from ancient inscriptions that the word kuriakos was a common word for anything imperial and that the first day of each month was designated as an imperial day when the ruling emperor was especially celebrated.

That day was referred to as kuriakos or the Emperor’s Day…This means Jesus Christ chose to reveal Himself [to John, the exile at Patmos] as the King of kings and Lord of lords on the very day that the entire Roman Empire was especially celebrating the supposed deity of the wicked Emperor Domitian.

It must have struck John that on the same day when the whole world was worshiping a fraudulent, evil human ruler, the True Ruler stepped into the forsaken place where John was exiled and revealed Himself in all of His glory to him”.

We do have, in the early second century, writings such as those of Ignatius and the Didache which mention Sunday as the Lord’s day. Perhaps John did receive the vision on a Sunday. Regardless, there are strong connotations of emperor worship in this phrase.

As early as the late first century we read from various sources that Christians were accused of cannibalism because they “ate” the body and “drank” the blood of their master.

They were accused of having incestuous relationships because they called each other “brother” and “sister” in their “love feasts.” They were even accused of atheism since they refused to believe the gods or offer sacrifices to the Emperor.

It's not until the second century that we begin seeing Christians addressing these issues. Many apologists began to write in defense of the Christian belief answering objections and correcting these aforementioned accusations.

Nevertheless, I find the courage and attitude of the early Christians very challenging and impacting. There was no middle ground for them.

Of course, they were encouraged to pay taxes, submit to leadership, give to Caesar what is of Caesars, but they were well aware that they could not serve both the interest of the Emperor and that of Christ.

Their allegiance could only belong to one king. The gospel was not a convenient message meant for personal comfort. It was an uneasy challenge. A matter of life and death. A price to pay. A declaration of rebellion to the evil spiritual powers of this world. I guess the question and challenge for us modern Christians is: where does our allegiance lie?

Marc Madrigal is a Board member in the Istanbul Protestant Church Foundation in Turkey.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dechow, Jon F. The ‘Gospel’ and the Emperor Cult: The ‘Gospel’ and the Emperor Cult. FORUM. third series 3,2 fall 2014.

Renner, Rick. A Light in Darkness, Seven Messages to the Seven Churches, Vol. 1, p. 41.

Elwell, Walter A. "Entry for 'Lord's Day, the’.” Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. 1997.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o