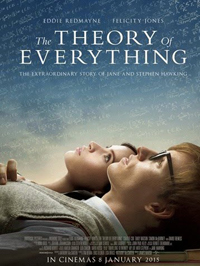

This isn’t a film about science but about the frailty of life. Although it revolves around the life of Stephen Hawking and his ideas, it is surprising how much the film talks about God.

Eddie Redmayne as a young Stephen Hakwing.

Eddie Redmayne as a young Stephen Hakwing.

(This article was first published: February 2015)

Ultimately, there are two ways of seeing the universe: as the result of an impersonal and random accident, or as the result of love, revealing a personal God. The quest for the truth behind everything has been the work of Stephen Hawking’s life. “What do cosmologists worship?”, the character of his wife (played by Felicity Jones) asks her future husband. “One single unified equation that explains everything in the universe”, answers Eddie Redmayne, when the scientist didn’t yet have the digital voice that we know today.

This is not a movie about the scientist, but about the frailty of life.

This is not a movie about the scientist, but about the frailty of life. This beautiful film directed by James Marsh – the director of two marvellous documentaries, “Man On Wire” and “Project Nim” –, uses extraordinary sensitivity to describe the place of faith and illness in the Hawking marriage. He does not shy away from some of its darker aspects, but suggests them with delicacy. Redmayne’s acting is spectacular, and Jones is even more delightful than in her role as Dicken’s secret love in “The Invisible Woman”.

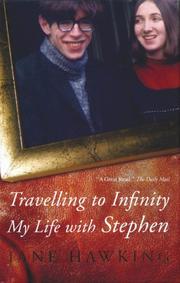

“The Theory of Everything” isn’t a film about science but about the frailty of life. Although it revolves around the life of a scientist who has been used by many atheists, it is surprising how much the film talks about God. The reason for this is that this isn’t Hawking’s story, but a story about his marriage. Marsh’s film is based on the memoirs of his first wife, Jane. This is her second book, “Travelling to infinity”.

A LOVE STORY

The story of the Hawking marriage was not unfamiliar to me. Through my connections to Cambridge, I have heard about Jane since I was a teenager, as she is well known in the churches that I have visited since the 1980s, around the time when Stephen became a worldwide celebrity with his book “A Brief History of Time”. She speaks perfect Spanish, holding a doctorate in Hispanic Studies. In fact, she says that she realised that she was in love with Stephen in Granada, while travelling around Spain after finishing her degree.

The story of this marriage shows how love faces all difficulties.

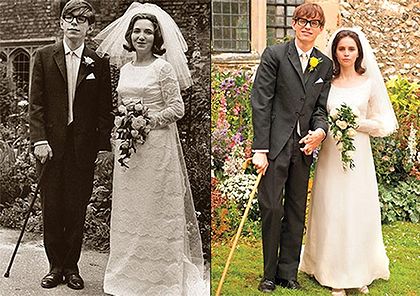

The story of this marriage shows how love faces all difficulties.Jane met Stephen in 1963, at a New Year’s party hosted by some friends in another city that I am familiar with, the ancient Roman city of Saint Albans, where they both lived with their families, before going to university. Hawking appeared awkward, but had a special something due to his peculiar sense of humour. He “managed to see the funny side of situations”, Jane says. He is known for making jokes about himself, which always make people well disposed towards him.

Only a month after they met, Stephen discovered the reason for his awkwardness, which not only made him stumble but even made tying up his own shoelaces difficult. The doctors diagnosed him with a terrible neurodegenerative disease, known as ALS (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis). It evidently did not affect his intelligence, but he was given a life expectancy of two or three years, at best. At first he did not say anything to Jane, but when he did it only brought them closer. They were so in love that, when they got married in 1965, they faced the challenge of his almost certain death.

A STRANGE QUARTET

Before becoming a celebrity, Hawking was already known in the world of science, but he was not surrounded by the army of nurses that he has today. At the age of 28, he was already famous for his work on black holes, but he didn’t have any multimillion-dollar contracts, and was not pursued by the press. Jane was the only person who looked after him, before hiring the seductive nurse Elaine, who won over Stephen’s heart, and for whom Stephen left his wife.

In this second book, there is less bitterness at that abandonment. Stephen is now divorced from his second wife, who has been accused of abusing him. This has helped his reconciliation with Jane, who is still married with a widower who she met at church, Jonathan Heller Jones. This organist and choir master had moved into their house to help her husband, but Stephen was aware that his faith and comprehensive attitude made his wife increasingly more attracted to him.

Neither the film, nor the book, suggest that the couple’s different attitudes to God were the reason that Stephen left her – as some people claim–. Jane is honest in that regard, and doesn’t believe in the faith heroine role that has sometimes been attribute to her. It is therefore interesting to hear Stephen himself recognize that he approved of the relationship between his wife and Jonathan, knowing that someone had to look after her as his own days were numbered.

Stephen had three sons with her first wife.

Stephen had three sons with her first wife.The fact is that it was he who left her in 1990 for Elaine, his nurse. Described in the book as “controlling, manipulative and bullying”, everyone agrees that she had a tendency for explosions of anger. When her husband suffered from sunstroke after she left him for hours in the sun, his daughter Lucy reported her to the police, but he refused to collaborate with the inquiry. The case was filed in 2004, but the couple did end up divorcing in 2007.

TRAVELLING TO INFINITY

Due to his experience making documentaries, Marsh does not turn this story into the melodrama that it could have been. The film has none of the clichés that are often found in “biopics”. It doesn’t seek to exploit the tragic side of the story through manipulative sentimentality. It is sometimes even cold and calculated, but the director sets the narration to a magnificent rhythm; it is perfectly staged and formally flawless. The film has that academic tone of British productions – elegant and well constructed– which is both the weakness and strength of British cinema.

Those who know Hawking’s work may feel disappointed, if they thought that the film was going to be about the scientist. It is Jane’s story. That is why Stephen’s figure is somewhat distorted. Marsh argues that it is impossible to transfer complex mathematical language to an understandable cinematographic message. Out of courtesy, the film script was sent to Stephen before starting to film, but it is based on Jane’s book “Travelling to Infinity”. Hawking said that he didn’t have a problem with it and when he was taken to see a private showing of the film, he appeared truly moved. He said that what he had seen was “broadly true”.

His identification with the film can be seen by the fact that he gave his permission for the use of his electronic voice, which he sees as an essential part of his identity. He will not allow it to be altered. The scenes filmed with Super 8 and 16 millimetres were shot for the film, but they are based on the ones found in the family archive in California. There are apparently a few scientific errors – such as the use of the term “black hole” before 1967 –, but at least, he talks about it surrounded by colleagues such as Thorne – on whose theories “Interstellar” was based; and that a wager made on a subscription to the pornographic magazine, Penthouse, was in fact to “Private Eye”, according to Stephen Hawking.

The subtlety of the film lies in the way that it suggests things, without showing them. Elaine shows him the magazine Penthouse, which he had won in the bet. When she asks him whether he wants to see more, we don’t hear his answer. She accompanies her future husband on a camping trip with his three children. When they go to sleep, she comes out of their tent, as if to go to his, but we do not see her going in. In this second book, his character is much less idealized than in the film, where he is shown to be extremely generous.

FAITH THAT FACES UP TO DIFFICULTIES

“Please Lord, let Stephen live!”, Jane prays when she hears that her husband is at death’s door. It was in the summer of 1985, when a bout of pneumonia left him in a coma while he was attending a summer course at CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Switzerland– he wasn’t just going to a concert, as it appears in the film.

They asked her permission to turn off his life support and allow him to die, but she refused, forcing them to carry out a tracheotomy to save his life. Jane turned to God in order to resist and keep her hope alive, even though Stephen mocked her “religious superstition”. According to Jane, he only believed in the “goddess Physics”.

Felicity Jones as Jane.

Felicity Jones as Jane.The fact is that Hawking become increasingly more atheist after leaving Jane. At first, he spoke about God in his books, even though he was not a believer. The strange thing is that Jane believes that the same illness that strengthened her faith, explains the atheism of Stephen. Jane says: “I understand the reasons for Stephen's atheist beliefs, because if at the age of 21 a person is diagnosed with a terrible disease, are you going to believe in God? I think not. But I needed my faith, because it gave me the support and comfort I needed to continue. Without my faith, I would have had nothing… But through faith, I always thought it was going to overcome all the problems that arose for me”.

This is the paradox of life itself. What makes some lose their faith, strengthen the faith of others. How is this possible? It would make no sense for faith to be based on simple circumstance. What sustained Jane was her trust in God “through darkness, pain and fear”. That is why she was surprised that Stephen could say that “miracles are not compatible with science”, because, in her eyes, his life is a real miracle.

While Stephen mocked her faith, Jane “fervently needed to believe that there was more to life than the bald facts of the laws of physics and the day-to-day struggle for survival.” For her, it was clear that atheism “could offer no consolation, no comfort and no hope for the human condition”. Even though her faith did not solve her problems – she sometimes found herself in such extreme situations that she was “restrained only by the thought of my children from throwing myself into the river”–, it supported her through difficult times.

AN HONEST ACCOUNT

The movie is based on the memories of Jane Hawking.

The movie is based on the memories of Jane Hawking. This is an honest book. It contains some very surprising anecdotes, for example, about the time when Stephen Hawking smuggled bibles into Russia, along with a group of Baptists, hiding them in his shoes. Many atheists will be flabbergasted by reading about such episodes. We are told how Stephen interceded with the Pope to rehabilitate Galileo and, like his colleague, the award-winning physical theorist John Polkinghorne, he decided to study theology, to be ordained into Anglican ministry.

One of the moments in the book that best describes Jane’s faith, is when Hawking took on an Christian American student, who spent every morning trying to evangelise him over breakfast. Jane warned him that “he was doomed to failure, for his broad, floodlit highway of biblical certainties was even less likely to meet with success than my own path, a quiet, unpretentious amble along the meandering lanes of simple trust in faith and deeds. Stephen had no patience for anything other than the rational power of physics.”

As Jane says in the film, Stephen understands cosmology as some sort of “religion for intelligent Atheists”, while she holds on to her faith. In this regard Stephen declares that he has “a slight problem with the celestial dictatorship premise”. The comment sounds brilliant, but it becomes ridiculous when he says that he is working on a theory to prove that God does not exist. The Bible tells us that God has provided evidence to the contrary.

“For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.” (Romans 1:19-20). If we do not believe, it is not for lack of evidence. The problem is that no one wants a “celestial dictator”. The question is whether that god is the God of the Bible. The miracle of Stephen’s life proves the opposite.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o