Balancing grace and truth in outreach.

‘Love is stronger than Fear‘ by Viv Lynch (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

‘Love is stronger than Fear‘ by Viv Lynch (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The ‘grace approach’ to Muslims—a resonant phrase adopted by mission leader Steve Bell as the title for his important book1—represents the noblest attributes in the Christian faith. ‘But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you’ (Matt 5:44).

Grace for Muslims?: The Journey from Fear to Faith by Steve Bell

Grace for Muslims?: The Journey from Fear to Faith by Steve BellAfter a year of violence across the Muslim world, much of it affecting traditional missionary-sending countries of Europe too, it is good to remind ourselves of the high standard of Christ2. However, as Bell makes clear, it is an approach that can only emerge from the truth. Anything else cheapens the cost.

BALANCING GRACE AND TRUTH

Bell himself has been ‘beaten at a North African border-crossing; spat at on a Cairo street; threatened on separate occasions with an iron bar, a cane, and a knife to my throat; lied to, and used’ by Muslims3. He was eventually thrown out of Cairo by Egypt’s notorious Secret Police. He has read and studied many of the writings of the fathers of the modern reincarnation of the jihad4. When he speaks of love, based now in Interserve’s new home in the area of Birmingham, Alum Rock, where a soldier was threatened with beheading for serving in the British Army, he speaks with authority.

An eyes-wide-open capacity to face and engage ‘the dark side’ of Islam is our missionary calling in a culture too used to its ease. However, as the following examples show, it is proving difficult to balance truth with grace. Anything less does not carry the imprimatur of the Holy Spirit and risks begetting more violence.

‘DESPERATION’

An English vicar last year chose an unusual topic for a sermon on Trinity Sunday: Islamic radicalism. Just three weeks before, 22 people, mostly children, out enjoying a concert at the Manchester Arena had been killed in cold blood as they left for home. Just eight days before, eight pedestrians on London Bridge and diners in Borough Market had been set upon with huge knives and had their throats slit. The vicar hit on his theme of the ‘rational incomprehensibility’ of the Trinity and the ‘irrational comprehensibility’ of these massacres. ‘They must have been desperate,’ he said. Their ‘desperation’ ‘explained’ their motives.

This is untrue, but manifests a homogenising tendency prevalent in Western culture. All faiths are not the same and their devotees are exposed to massively dissonant influences that are too easy for us to ignore.

‘ANGLICISING’ ISLAM

Colin Chapman, formerly the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Special Envoy to Al-Azhar University in Cairo and a Principal of the Church Mission Society training college in Birmingham, UK, is another Christian who has lived and worked among educated Muslims. However, he downplays the differentness, or as Steve Bell puts it, the ‘strangeness’ of Islamic culture to many non-Muslims.

His generous concern for Muslims risks lulling his readers into a false sense of the adequacy of our responses through, in the words of the anthropologist Roger Ballard, ‘Anglicising’ Islam. Others, less charitably, call it ‘colonialism’, attributing to Islam and its followers motives and manners that colonise their thought worlds, rendering them familiar, and therefore comfortable to handle.

Chapman, an influential writer, lived for many years in Beirut. He regards Islam as generally more sinned against than sinning. Like the vicar, he finds reasons for atrocities. In a long piece for Fulcrum5 last year, which was reprinted from Transformation6, he gives nine examples of Islamist—political—movements that used violence: ‘In every case there has been something contextually specific—a perceived injustice—which has driven Muslims to take action and often to resort to violence.’ This is not necessarily true. Two recent commentators attribute violence in the Levant to ‘testosterone’ and sexual frustration7, as does much of an issue of the Muslim Institute’s acclaimed Critical Muslim journal devoted to ‘Men in Islam’8.

While acknowledging ‘that political Islam does not necessarily sanction violence’, he goes on to justify it in a generalisation that appears to disavow Islam’s own highly complex categories of violence and the discussions that surround its use. Says Chapman: ‘At the same time it is not hard to understand how some Islamists, who are frustrated at the slow progress in creating a more Islamic society or who suffer extreme violence from their opponents, can conclude—from their scriptures, dogma and history—that they have adequate justification for turning to violence.’

On jihad Chapman asserts, ‘As is well known, the basic meaning of the word jihad is ‘to strive’, and has little to do with the idea of ‘holy war’—an assertion that is roundly contradicted by, for instance, Saudi scholar Madawi al-Rasheed at King’s College, London.’9

Chapman rightly and strenuously seeks ways to approach and humanise Islamists, but in such a way that leads Melbourne-based Anglican priest and Quran specialist Dr Mark Durie to accuse him of ‘imposing reality’ on Islam: a missionary tactic that ‘does not promote peace’, he adds10.

SCRIPTURAL ROOTS

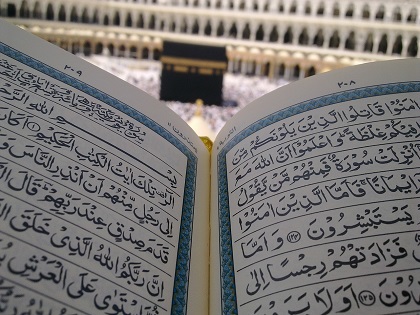

Shiraz Maher, former member of terror group Hizb ut Tahrir, is now Deputy Director of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) at King’s College London. Last August, Penguin published his doctorate on the scriptural and traditional roots of Salafi-Jihadism11. ‘For every act of violence, they [IS] will offer some form of reference to scriptural sources—however tenuous, esoteric, or contested.’ Tom Holland interviews Maher in his film, ‘IS: the Origins of Violence’. He compares Quranic texts to ‘unexploded bombs’, lying in wait for centuries for the next grievance to co-opt them into murderous service12. Maher says: ‘Yes, Islamic State is more brazen and ruthless than its predecessors but the ideas that guide it are well established in radical Sunni thought. . . . This is a broad and varied ecosystem of dense Islamic jurisprudence that has licensed the actions of militant movements across the world. Islamic State is just the latest and most successful group it has spawned.’

As missionary-minded Christians we should know about this killing code, which finesses to an astonishing degree when it is right to kill for the faith. Take one example: the law of qisas of equal retaliation: ‘When militants apply qisas as an instrument of international law they hold every citizen-stranger of an enemy state liable for the action of their government’—liable in fact to be killed for apostasy.

The leader of al-Qaida Ayman al-Zawahiri believed that ‘forfeiting the faith was a much greater harm than forfeiting money or lives.’13 Even some jihadi leaders find it hard to stomach the blanket anathemas against Muslims of their peers, according to Maher. Yet Chapman dismisses as ‘textualism’ the attempt to take seriously Islam’s own huge internal literary dynamic, rooted and justified in scripture and the traditions to a degree only now coming to wider notice. The ‘grace approach’ to Muslims recognizes this use of scripture to control and terrify, while at the same time discerning the spiritual need of individual Muslims, and challenging them with the freedom from fear that Christ promises in scriptures for which Mohammed himself commanded respect14.

SUPREMACY AIM

Jihad is the predominant virtue in a hierarchy of virtues for this kind of Islam. ‘At its core the contemporary Salafi-Jihadi movement regards physical struggle in the cause of God as the pinnacle of Islam, its zenith and apex.’15 With Islam now dispersed throughout the West—the former dar-ul-harb or ‘land of war’—that means total and constant war-mongering for its own sake by Salafi-Jihadis to which we must become wise, as the fear it causes, especially to Muslims themselves, infects the broader populace.

Islam must defend itself, until it is vindicated by its dominance and we must understand this, and learn to resist it. Where Islam is dominant, churches will burn—as they have done in recent years in Egypt, Iraq, Turkey, Kosovo, Algeria, Kuwait, Pakistan, Iran, South Sudan, Mali, and elsewhere16. Mark Durie, who recently led a mission into Ethiopia, a Christian majority country, recounts how churches have, nonetheless, burned in the Muslim-majority north17:

Ethiopian Christians oppose Islamisation and resist it in many ways. Surrounded by Muslim nations, Ethiopia stands as a testimony to the effectiveness of Christian resistance to jihad, and also to indigenous African Christianity. Christians here have had a lot of experience in learning how not to surrender power to Muslims. However some regions of the country have very high percentages of Muslims, particularly those in the north east, and in these regions Christians can be persecuted, e.g. by church burnings or attacks on believers. Apparently the same does not happen to Muslims in Christian-majority areas.

THE GOOD NEWS

The good news of Jesus is the only antidote to the fear and hatred Islam sometimes justifies. The possibilities of authentic, courageous outreach are there to be had.

A market town in the Chiltern Hills, west of London, now hosts some of the most blood-curdling jihadis to have left these shores18. Yet Pakistani Christian, Amjad M, recently co-hosted a qawwali evening of traditional sacred songs at his home there, with one of three imams who are noted preachers of martyrdom. It turns out that the host had taught his daughter at school.

One further example - from Ethiopia - illustrates the grace and truth approach:

Years ago there was a news report that a church had been burned and Christians from that church had had their throats cut by their Muslim neighbours. A young seminary student was moved with compassion for the Muslim community connected to that atrocity, and wanted to go to share Jesus with them. When he could find no church to back him, he stepped out on his own, trusting God to provide. It was not easy. He did find one Muslim man who wanted to follow Jesus and discipled him. That one man then led his family to Christ, and the ministry began to expand. That once-young evangelist is now the middle-aged pastor over a rapidly growing movement19.

Jenny Taylor is a writer, journalist and consultant who has worked across the media, including the Independent, the Times, the Spectator and the BBC.

This article originally appeared in the March 2018 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis and is published here with permission as part of the LGA Media Partnership. Learn more about this flagship publication from the Lausanne Movement at www.lausanne.org/lga.

Endnotes

1. Steve Bell, Grace for Muslims?: The Journey from Fear to Faith (Milton Keynes and Hyderabad: Authentic, 2006).

2. Editor’s Note: See article by Wafik Wahba entitled, ‘Witnessing to the Gospel through Forgiveness: a living example from the persecuted Christians in Egypt’, in the January 2018 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2018-01/witnessing-gospel-forgiveness.

3. Bell relates this in his article ‘Grace for the Dark Side’ published by Interserve, New Zealand in Go magazine, Issue 1, 2010.

4. Editor’s Note: See article by an author whose name is withheld (not Steve Bell) entitled, ‘What is the Islamic Caliphate and Why Should Christians Care’, in May 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-05/islamic-caliphate-christians-care.

6. An International Journal of Holistic Mission Studies, 34:2 (March 2017), 115-30.

8. Critical Muslim Volume 08 - Men in Islam – edited by Ziauddin Sardar and Robin Yassin-Kassab.

9. Madawi al-Rasheed, ‘Rituals of Life and Death: the Politics and Poetics of Jihad in Saudi Arabia’ in Madawi Al-Rasheed and Marat Shterin, Dying for Faith (Tauris 2009), 81.

10. See Durie’s comment at the end of Chapman’s article ‘Christian Responses to Islamism’.

11. Shiraz Maher, Salafi-Jihadism: the History of an Idea (London: Penguin, 2017).

12. Jonathan Birt has researched, as a participant observer, the development of a ‘grievance theology’ by young British Muslims, for whom Chechnya was considered too distant, and the local Muslim community ‘morally corrupt’. ‘It was necessary to look outside for a grand cause – in this case, the cause of global jihad’. In ‘The Radical Nineties Revisited: Jihadi Discourses in Britain’ in Madawi al-Rasheed & Marat Shterin (eds) Dying for Faith: Religiously Motivated Violence in the Contemporary World (London & New York: I B Tauris, 2009), 107.

13. Shiraz Maher, Salafi-Jihadism: The History of an Idea (London: Penguin, 2017), 63.

14. Editor’s Note: See article by Ida Glaser entitled, ‘How Should Christians Relate to Muslims: Developing a Biblical Worldview on Islam’, in May 2017 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2017-05/christians-relate-muslims.

15. Shiraz Maher, Salafi-Jihadism, 32.

17. Author’s personal correspondence with intercessors.

19. Prayer letter to author.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o