Ukrainians celebrated their 34th anniversary of breaking from the Soviet Union with deep gratitude to God, and for their loved ones who have given their lives to keep their country free.

![Photo via [link]Weekly Word[/link].](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/68ac16dc4eb4b_Ukind940.jpg) Photo via [link]Weekly Word[/link].

Photo via [link]Weekly Word[/link].

How much do we value the independence of our nation?

Most of us in western nations take independence for granted. We’ve never known anything else.

But this Sunday Ukrainians celebrated their 34th anniversary of breaking from the Soviet Union with deep gratitude. Gratitude to God, and for their loved ones who have given their lives to keep their country free from domination, suppression, and attempted erasure.

For most of its history, Ukraine has existed under the shadow of foreign powers—Polish, Lithuanian, Austrian, Ottoman, and most significantly, Russian. Independence for Ukrainians is about reclaiming a voice, an identity, and the right to chart their own destiny.

August 24, 1991, is a date for them to celebrate. In churches across the country, Ukrainians will be thanking God for their hard-fought freedom, and seeking his protection against the aggressor.

And they have appealled to congregations around the world to stand with them in prayer, both of thanksgiving and supplication. Lausanne Europe, 24-7 Prayer and the European Evangelical Alliance are among the many faith networks supporting this appeal.

Yesterday in St Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, President Zelensky started a 24-hour prayer chain which will culminate on Monday morning with his address to the National Prayer Breakfast.

Shortly after the Russian invasion began 1276 days ago, the president led his nation in prayer from that cathedral in a prayer we have featured before as an excellent framework for our own prayers.

I write this column as I travel to Kyiv for the Prayer Breakfast. It is my first visit since before COVID, when we could fly directly in less than three hours into Kyiv from Amsterdam. This journey is spread over three days – by train, plane, bus and car.

For the Kremlin, however, this date represents the ‘greatest catastrophe of the twentieth century’, the breakup of the Soviet Empire. Vladimir Putin will not rest until he has restored Russkiy Mir, i.e. Russia’s claim to an historic right to dominate its neighbours.

So his talk of ‘peace’ at this stage is simply about breathing room for him to prepare for his next attempt to ‘restore the rightful order’.

The Kyiv Independent reported last week evidence of his plans to turn the occupied territories of Ukraine into a militarised zone as a launching platform for furthering his goals.

For centuries, Ukraine’s fertile lands—the so-called “breadbasket of Europe”—were both a blessing and a curse. They attracted empires that sought to control its resources and trade routes, as we have been exploring in this column in recent weeks.

From the late 18th century onward, Russia sought not just to rule Ukraine but to suppress its national consciousness. Ukrainian language, literature, and history were banned or rewritten to fit Russian narratives. Ukrainian identity was tolerated only as folklore, never as a political or cultural force.

Under Soviet rule, the suppression became even more brutal. The Holodomor famine of 1932–33, engineered by Stalin, killed millions of Ukrainians, not only as collateral damage of collectivisation but as a deliberate attempt to break Ukrainian resistance.

Ukrainian church leaders, intellectuals and artists were purged. The Soviet project aimed to make Ukraine a seamless part of a “greater Russia,” erasing its independent traditions.

Even when Ukraine became a Soviet republic, it was never free. Its borders, economy, and leadership were determined in Moscow. The so-called independence of the Ukrainian SSR was a fiction, a mask for Russian imperial control.

Independence in 1991 was an act of recovery. It meant that Ukrainians, long told that they were merely “Little Russians,” could openly affirm: ‘we are a people in our own right’.

Independence enabled the revival of the Ukrainian language, once suppressed but now central to national life. It stimulated the rediscovery of Ukrainian history—not as a footnote of Russia’s past, but as a story of a resilient people with their own heroes, martyrs, and culture.

Independence has also meant spiritual revival. Since 1991, religious freedom has returned, and in 2019, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine was granted autocephaly, symbolizing religious as well as political independence.

Unlike in Russia, there is freedom for the whole range of denominations, with restrictions only on the Moscow-linked Ukrainian Orthodox Church due to the war conditions.

Independence also brings responsibility. Freedom is fragile, easily squandered by division, corruption, or apathy. True sovereignty requires not only resisting external domination but building institutions that serve the people, upholding the rule of law, protecting minorities, and ensuring that independence is not just for the elite but for every citizen.

Ukraine’s independence has a message for the other former republics of the Soviet Union, and for the whole world. It proclaims that every nation, however often suppressed, has the right to exist, to speak its language, to remember its past, and to shape its future.

Ukraine’s courage calls us all not to take independence for granted, but to recognise its cost and its value.

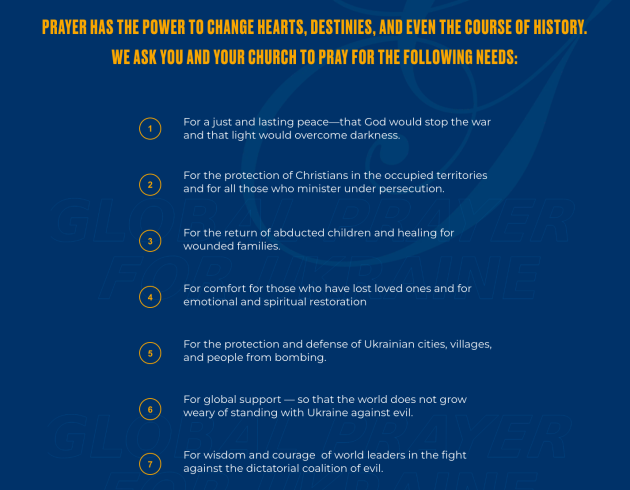

[photo_footer]These prayer points can guide us as we join Ukrainian believers in prayer for their nation, wherever in the world we may be. [/photo_footer]

Jeff Fountain, Director of the Schuman Centre for European Studies. This article was first published on the author's blog, Weekly Word.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o