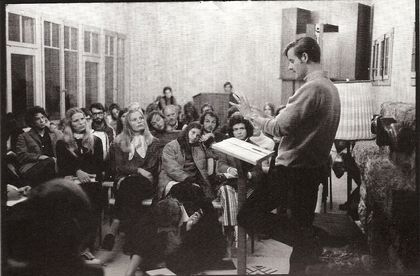

In search of authenticity (4): Schaeffer was looking for the human contact that might reopen the discussion that the debate had closed.

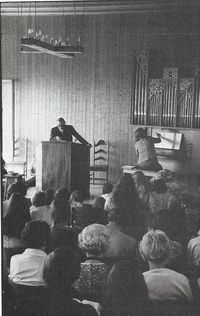

Schaeffer was not so much an academic as an evangelist.

Schaeffer was not so much an academic as an evangelist.

According to Schaeffer, "biblical orthodoxy without compassion", was, "the ugliest thing in the world". If there was someone who cared for the truth, that was he. The "real truth", as he called it. But truth without love is monstrous, he thought.

What he most lamented about his younger days was this very fact, the ruthless zeal with which he defended "sound doctrine". He understood his critics, because he had been one of them. This second to last article on Schaeffer´s legacy talks about them.

At L'Abri people shared meals, meetings, walks and practical work, although it wasn't a Mennonite type of community.

At L'Abri people shared meals, meetings, walks and practical work, although it wasn't a Mennonite type of community.Following the personal crisis that led to the founding of the L´Abri community in 1955, his former collaborator Carl McIntire reproached him for nothing less than being a "Communist".

Ludicrous comments of this kind were the mark of the new fundamentalism during the "cold war period". They saw ghosts where there were none.

If Schaeffer´s ideas could be described in any way, they would be termed Conservative. What McIntire probably referred to was their concept of community.

At L´Abri people shared meals, meetings, walks and practical work, although it wasn´t a Mennonite type of community.

Fran continued giving pastoral theology classes right up to 1954, at the Faith Theological Seminary of the Bible Presbyterian Church, which had been born out of the division of Westminster Theological Seminary and the Orthodox Presbyterian Church.

The separation of historical fundamentalism that gave rise to the new fundamentalism, is always based on the degree of separation from those 'guilty by association' and the question of "Christian freedom", which leads to sectarianism and legalism, and this continues to mark these types of churches to this very day.

The conflict broke out in the course graduation talk of 1954, which was titled "Tongues of fire". He spoke of the need to maintain the truth by "the only source of power of the people of God, Christ himself".

At the end, a leader of the denomination told his wife Edith that there was going to be a division. This happened the following year after L´Abri started, when the Synod divided into two and the Covenant College was born, where the Institute that carries Schaeffer´s name can be found.

As L´Abri was not a church, the communities that were born of it became a denomination, which has grown considerably in Great Britain and is called the International Presbyterian Church. The best-known branch these days can be found in the London district of Ealing.

In one sense, Schaeffer continued to be a fundamentalist. Samuel Escobar recalls his insistence on the term "inerrancy", during the preparatory meetings of the Lausanne Congress in 1974. Although the word means the same as "infallibility" – which is the usual expression used in English by the historic denominations-, Evangelical conservatives like him thought that it was not sufficient.

In the final analysis Stott´s view was upheld and he drew up the final document draft in which the word “inerrancy" is not found. Schaeffer is one of the discontented who founded the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy in 1976, which made a statement in Chicago the following year.

L'Abri was not a church, the communities that were born of it became a denomination, which has grown considerably in Great Britain and is called the International Presbyterian Church.

L'Abri was not a church, the communities that were born of it became a denomination, which has grown considerably in Great Britain and is called the International Presbyterian Church.On the other hand, Fran evidently gets rid of the concept of fundamentalist separation, which had fostered a pietism alienated from the world. His message is extremely contemporary, full of references to the culture and art of his time, which he places in relation to the Gospel.

Additionally he speaks about music, movies and books that even the Liberal theologians were not commenting, since they were more interested in the "social Gospel", than in the counterculture of the 60s.

He is not afraid to attend rock concerts, watch what could be considered immoral films, or of reading Existentialist literature. All these are examined and tested in the light of the word of God, to show Christ's truth.

ACADEMIC OR EVANGELIST?

Some scholars have despised Schaeffer work as "simplistic, superficial and partisan". They described it as a "concatenation of groundless judgements, based on half-truths", that border "paranoia".

There have also been teachers who have criticized his vision of Thomas Aquinas or Kierkegaard, his idealizing of the Reformation and his maintenance of "the myth of Christian America". All of them are questionable aspects of his work, but his critics forget that he was not so much an academic as an evangelist.

His 1954 doctorate was honorary. He never intended to be any kind of specialist. He was more interested in the broad outline rather than the detail. He was afraid he would not see the woods for the trees.

Schaeffer´s work cannot be judged for his misguided view of an author or a specific time. He likes to cite names, but that does not mean he knew them well. He tries to find references that will help him identify with the unbeliever, rather than an in depth analysis of someone´s particular works. He is always noted for his open mindedness.

L'Abri was not intended to be a place for retreats in which people lose contact with reality.

L'Abri was not intended to be a place for retreats in which people lose contact with reality.That is why despite his training in classical music he loved to quote rock bands. He wasn't one-tracked, everything interested him. He doesn´t talk about his own tastes but rather the wider musical culture around him. His intellectual curiosity knows no bounds. There was no shame in not knowing something but there was nothing worse than not wanting to know. That is the problem for most of us, not that we don´t know something, but that we simply aren´t interested in discovering it.

To Schaeffer, nothing about humanity was a no-go zone. This is the reason that he rejects calling L'Abri, an intellectual forum. He was concerned about “real life” rather than academic discussion. He had time for “genuine questions and no time for controversy”. On the other hand, he shied away from the super spiritual “mountain top experience” He didn't want L'Abri to become a place to retreat into away from the world and reality. This is why Fran always talked openly about his struggles and failures.

MORAL MAJORITY?

The criticism received from fundamentalists and academics can be added to his uncomfortable position in his Moral Majority role during the Reagan administration, which was at the start of the 80s and was shortly before his death.

This period of his life is less well known in Spanish-speaking circles because his book “A Christian Manifesto” (1981) was never translated. However, Editorial Vida did publish the text, which is the base for a series of documentaries that he carried out with Everret Koop, a Christian pediatrician and a friend of the family who had treated his daughter Prisca back in 1950 when he was head of the American health authority “Whatever happened to the human race?” (1983)

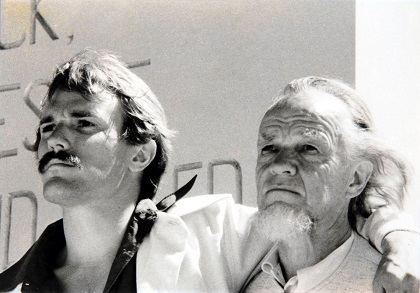

Until 1977, Schaeffer´s work relates Christianity with culture, but avoids the socio-political emphasis that characterizes the American conservative world that he came from. It was a fundamentally European reflection, reflecting the documentary series from a historical perspective "How should we then live?" (1976). the idea of making these films comes from his son Franky.

Born late, after his three sisters, the only male child of the family, he received the maximum attention from his mother as he suffered from polio from the age of two. He escaped from the school where he was boarding in England, and was educated at L´Abri, without going to any official school. He was 23 when he directed the series.

Franky now accuses his father of being the "intellectual architect" of the American religious right but, who got him into that "culture war" which confronted American society on abortion from the end of the 70s? The very Franky!

The complex relationship of father and son is now part of American popular culture. This is because Franky wrote books like "crazy for God: how I grew up as one of the elect, helped found the religious right, and lived to go back on everything (or almost everything) "(2007) or his trilogy of novels about Calvin Becker, “son of a reformed Kansas Presbyterian missionary family based in Switzerland "and his "volcanic sexual curiosity".

Franky now accuses his father of being the creator of the Evangelical Right.

Franky now accuses his father of being the creator of the Evangelical Right.After spending some time painting, he writes three books in the 80s, which bear his father´s ideas and which were written in a harsh, uncompassionate way until he began directing horror movies, not of the B type but more the Z type, almost “gore”.

He abandons evangelicalism in 1990 after becoming a Greek Orthodox and defines himself as an “atheist who believes in God”. After launching his father as the founder of Reagan's Moral Majority, he abandons the religious section of the Republican Party and dedicates his time to glorifying the Marines after his son joined up.

Now he is a liberal democrat but he continues to talk about his parents. He is now 64 and seems to have got stuck in the oedipal phase of “killing the father figure” in order to keep the mother figure all to himself, as shown by his book “Sex, mother and God (2011)

Schaeffer´s critics do not know what to make of him as he exalts his father or, with the same breath accuses him of being an abuser. He always mentions his mother. If you read his obituary for her in the Huffington post, you can clearly see his unhealthy attachment to her.

His obsession with sexuality took him into areas that would be unacceptable for those who idealize L'abri and the Schaeffers. He described that marriage as “disastrous” but equally towards those who despise his "fundamentalist education" because, for Franky, family is everything.

At times he shares the genius and creativity of his father but he is also often “addicted to the mediocre” which he despises. He has always lacked the compassion that his father had.

GENEROUS ORTHODOXY

If "no critic has done so much damage to his life's work as his own son -said Os Guinness-, with a child like that, who needs enemies?". The grace that his mother showed, even after the terrible things that he wrote about her marriage, is a reflection of the generosity that his father always had.

"The problem isn´t so much that Frank revealed and made public the flaws and weaknesses of his parents", said Guinness – which is something that Schaeffer always acknowledged-, "but that he should accuse him of hypocrisy and insincerity, which was something that was at the heart of his life and his work".

Guinness who, like Edith, was a son of missionaries in China, was a part of L´Abri for six years – during which time he wrote what for me is his best book The Dust of Death, but then he abandoned the community, accusing Schaeffer of nepotism.

As happens in many organizations, family gets entangled in the ministry, but "whatever his flaws and failings on matters of historic detail and philosophy", Guinness says that "I have never met nobody like Francis Schaeffer, who took God, people and the truth, so passionately and seriously".

Os Guinness, son of missonaries in China, was in L'Abri for six years.

Os Guinness, son of missonaries in China, was in L'Abri for six years.As my teacher, Jerram Barrs, of the London Institute for Contemporary Christianity and who was a collaborator of L'Abri, said: "Schaeffer believed passionately that the Fall is a historical fact that has changed all life.

In particular, this meant to him, that he should be always aware that he was a sinner in thought, word and deed. It was mercy and God's faithfulness, which brought such unexpected blessing to his ministry rather that his own gifts, skills, abilities, power or self-righteousness”.

It is this awareness of God's grace, which helped him show the same grace towards others. It gave him a sense of the dignity of every human being - whereby "for God, there is no one too small", as he used to say - and a compassion that led him to avoid aggressive confrontation with his enemies.

One of the most amazing stories I've read about Schaeffer, is when he was giving a seminar in London and during discussion time, someone made the typical untoward comment, similar to the aggressiveness that now characterizes internet discussions... do you know what he did?

At the end of the meeting, many wanted to talk with the speaker, but he searched out the person that had attacked him, to show him that their differences did not mean that he did not want to relate to him.

He was looking for the human contact that might reopen the discussion that the debate had closed. It is that same compassionate orthodoxy he had learned from The Pastor who left his ninety-nine sheep, to search for that which was lost (Luke 15:4). Social media would look quite different if those who love the truth were to follow his example.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o