The first of a series of articles on Schaeffer’s legacy and on the challenge he still poses to the world today.

encastellano.jpg) A biography of Francis Schaeffer (1912-1984) has been published in Spanish.

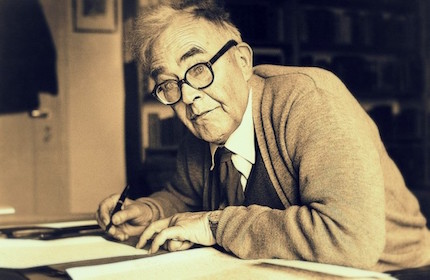

A biography of Francis Schaeffer (1912-1984) has been published in Spanish.

At long last a biography of Francis Schaeffer (1912-1984) is published in Spanish. There are already many written in English, but the one published by Andamio is one of my favourites.

This is perhaps because it isn´t written by a theologian, philosopher or apologist, but by an expert in fantasy literature, such as Colin Duriez, one of the greatest scholars on the works of Tolkien and C. S. Lewis. His choice for a title is what I think best describes Schaeffer´s life and work, the search for authenticity.

It is no easy task to sum up in a single article Schaeffer’s´ biography and thinking. I have read most of his books, but also many of his letters, as well as many studies that have been published about him.

Most of all and in more recent years I have had access to his family, thanks to the appreciation and enthusiasm that his son-in-law, Ranald Macaulay, has so generously shown me. This is why I have decided to write a series of articles on his legacy and especially on the challenge he still poses to the world today.

This is, of course, my personal opinion! Schaeffer means many things to many people. Most of them, I fear, continue to see him as an intellectual who wrote complex apologetic works. Anyone who believes that shows he has not fully read Schaeffer.

Moreover, he is unaware of Schaeffer´s personal influence, which for me is his greatest legacy. He was a great listener; he learned more from listening than from reading up and he was an excellent conversationalist. He cared more about people than books. However, one book, the Bible, changed his life completely. For him, Christianity was biblical, or it was simply not Christianity.

The truth is that his Christianity was experimental. He was a man of prayer, but above all he sought authenticity. This gave him a total dislike for the super-spirituality that sweeps the evangelical world.

Jose Grau, who is perhaps his main introducer to the Hispanic world, says that this is one the aspects of Schaeffer´s works which is “prophetic”.

This aspect is, if I may borrow Grau´s expression, an issue still pending for the more conservative evangelical Christian world, as pietistic and inhuman then as it is now.

For others, however, Schaeffer is too conservative. Many in liberal circles described him as "the guru of fundamentalism." The guru bit came from his connection with the hippy environment of the late 60's and early 70's, but also because of the extravagance of his Tyrolean dress manner and his approachability within a world as conventional as that of Evangelical Protestantism, where preachers still wore suits and used the same centuries old godly language. What was surprising to the liberal world was that his message remained so "fundamentalist." But fundamentalist it was.

GURU OF FUNDAMENTALISM?

To understand Schaeffer´s background we have to understand what fundamentalism meant in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The main historical denominations of Protestantism were divided because their theologians were moving away from the fundamental doctrines of Christianity.

Francis came from a German Lutheran family which had emigrated to the United States. The German school of Bible critique had established an academic empire, where scepticism and intellectual pride was rampant, two things which young Schaffer opposed not only because of his humble origins - the son of an unschooled, uncultured carpenter, but because of his humble attitude.

Schaeffer joined the Orthodox Presbyterian Church and the Theological Seminary of Westminster.

Schaeffer joined the Orthodox Presbyterian Church and the Theological Seminary of Westminster.Fran, as his family and friends called him, had dyslexic problems. When one listens to his recordings, one perceives not only the sharpness of his voice, but also the strange pronunciation he had for some names. His daughter remembers how, as a child, her father asked her to spell out very simple words.

A high school teacher broke him in to the world of art. And although he attended a Presbyterian church, he read the Bible for himself, since the denomination in which he was then attending, was not conservative.

He then joined the church built by Gresham Machen when it separated from northern United States liberal Presbyterianism which was when the Theological Seminary of Westminster in Fidaldelfia was founded.

His conversion occurred when he chanced on an evangelical mission tent-meeting in 1930. This was far removed from the nominal Protestantism of his parents. The following year he wanted to enter Hampden-Sidney University of Virginia, later to study theology.

His father saw pastors as parasites, who did no real work, but even so he agreed to pay him the first semester of general studies in philosophy and classical languages. There was an association of Christian students, which he got to preside, but whilst southern racism still prevailed, Schaeffer instead went to an Afro-American Sunday school.

Years later, his interest in Negro music led him converse with Hans Rookmaaker, the art scholar, who was passionate about jazz and film. They met at the International Council of Christian Churches, Amsterdam 1948, which coordinates fundamentalism as an alternative to the World Council of Churches.

They were so engrossed in their conversation subject that they missed going to meetings and instead walked the canals talking all the time about the relationship between the faith they had found after their conversion and popular culture.

The Dutchman had come across Christianity in a Nazi concentration camp, Auschwitz, where his Jewish fiancée died. He later became a member of a reformed conservative church. His current girlfriend worked as a secretary at the fundamentalist congress.

CHAMPION OF ORTHODOXY

Schaeffer married Seville, the daughter of evangelical missionaries serving in China.

Schaeffer married Seville, the daughter of evangelical missionaries serving in China.Schaeffer married the daughter of evangelical missionaries serving in China. His parents were in the China Inland Mission, founded by Hudson Taylor. It was a "mission of faith" that sought cultural adaptation, even in the case of the missionaries themselves. Edith's last name was Seville.

Fran met her at the Presbyterian Church at a youth gathering where a Unitarian lecturer denied the deity of Jesus and the divinity of the Bible.

Schaeffer debated with the speaker and recommended Machen´s book, "Christianity and Liberalism" (1923) to Edith. The year they married also saw the founding of the Westminster Seminary in 1935 where Fran enrolled in the first year, after graduating in Hampden-Sidney.

In order to understand to what extent Schaeffer was a fundamentalist, one needs to understand which part he played in the debate that took place in Westminster in 1937 on Christian freedom.

After forming the Orthodox Presbyterian Church with Machen, who also founded the seminary, a group led by Oliver Buswell and Carl McIntyre, the founder of the International Council of Christian Churches in New York in 1941, they saw the need for a new denomination, the Bible Presbyterian Church, which was to be consistent with the conduct of " Christian separatism from the world" and premillennial eschatology.

This "neo-fundamentalist" group founded the Faith Theological Seminary and the Schaeffers joined it. The Seminary ruled abstention from alcohol and tobacco - in Westminster they drank and smoked freely- as well as avoiding variety shows and dancing.

Fran was the first minister ordained by the denomination. He became pastor of two churches in Pennsylvania, one in Grove City from 1938 and another in Chester from 1941, before continuing to the third in St. Louis, Missouri, for a further five years.

The Schaeffers were known for their ministry among children. They organized summer Bible schools and founded a missionary organization called Children for Christ, a fundamentalist split from the Alliance for Child Evangelism (APEN), and which sent them to Europe in 1947.

The Schaeffers were known for their ministry among children, like this summer Bible school in the church of Grove City, Pensilvania.

The Schaeffers were known for their ministry among children, like this summer Bible school in the church of Grove City, Pensilvania.

On that trip they visited France, Switzerland, Norway and Holland. They were at the Emmaus Bible Institute, after visiting some pastors in Lausanne and attending a Baptist church in Oslo, at the same time as the World Council of Churches was holding a youth congress.

In Lausanne they established their operations base. Fran gave lectures on the dangers of liberalism. He travelled to Scandinavia, France, Germany. Whilst he was in Rome the dogma of the Assumption of Mary was proclaimed. This prompted him to write about the dangers of Roman Catholicism.

FAITH CRISIS

It is evident that many evangelicals still find themselves in Schaeffer`s pre-crisis phase, a crisis which occurred in Switzerland in the 1950s. They see the dangers of liberalism, Roman Catholicism and the ecumenical movement. They do not see how a Christian can drink or smoke.

They believe that biblical doctrine includes even their own particular eschatological position on the millennium. They must be separate from the world. The problem starts when someone like Fran has doubts about himself more than doubts about the Bible. This honest attitude drives him to search his own heart deeply.

Schaeffer warned about the dangers of Barth's new modernism.

Schaeffer warned about the dangers of Barth's new modernism.Schaeffer had studied at Westminster with a Dutchman named Van Til, who combined presuppositional apologetics with one of the earliest attacks on Karl Barth's theology of a "new modernism," in saying that the Bible contains, but is not the actual Word of God.

His view of Aquinas is the same as that of Van Til, but he differed with him in the radicalism of the view that there was no possible connection between a believer's faith and the non-Christian worldview.

It is interesting to note that Van Til never chose to disagree with him in public. Schaeffer told Rookmaaker that when he became a pastor he relied so much on his persuasiveness that if the other person did not accept Christ, he thought his own arguments must be unconvincing.

When they went to Switzerland, the Schaeffers already had three daughters. His health was not very good. They thought it was due to the local regional climate of the place where they had settled in a pension in La Rosiaz. They moved to Champéry, where they worked with English girls who spoke no French.

It all seemed rather strange whilst they prepared to hold a congress in Geneva where Fran was going to speak to the International Council of Christian Churches about the dangers of Barth's "new modernism." He then has personal contact with Barth.

His bitter correspondence can now be found on a Spanish internet blog. What many people don´t realise is that this happened just before the crisis he had in the 1950s, when he gave up being a missionary.

At the end of his life, dying from cancer, Schaeffer wrote this book lamenting is the excesses of his fundamentalist past.

At the end of his life, dying from cancer, Schaeffer wrote this book lamenting is the excesses of his fundamentalist past.He relates this experience in the prologue to his book "True spirituality", published in 1971. I will write about that in my next article. Reading this book was a really liberating experience for me. Like many people who have been raised in church, I also went through a doubting phase.

Some, like Schaeffer, have become Christians in adult life, but they sincerely question the reality of that experience when they get doubts about their spirituality further down the line. What is surprising is that he was pastor, missionary and lecturer, but he had the courage to say out loud what many of us hide in our hearts.

The greatest lesson we can learn from Schaeffer about fundamentalism is that one can be a champion of orthodoxy, seek ecclesiastical purity and live according to the strictest evangelical law, but be fooling oneself.

At the end of his life, dying from cancer, he remembered those years and lamented his crusade for truth which had lacked the love that comes from the Spirit of God in Christ Jesus. He had orthodoxy, but not orthopraxis.

In his view this is "The great evangelical disaster," the title of the incomplete book he wrote whilst in hospital and which has never been translated. We can have great zeal for the truth, but little of the love through which the world will know that we are Jesus´ disciples (John 13:35)...

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o