The intersection of physical and spiritual health among frontier peoples.

![Photo: [link]Ninara[/link], Flickr CC.](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/65f000d77d9f7_lgakids940.jpg) Photo: [link]Ninara[/link], Flickr CC.

Photo: [link]Ninara[/link], Flickr CC.

The Gapminder Foundation[1] and Our World in Data,[2] among others, have vividly described improvements in global health since the 1960s including child mortality,[3] life expectancy, and development.

Many improvements resulted from economic, educational, and technological advances, particularly after colonialism waned across the Majority World. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) ‘Alma Ata Declaration’ of 1978,[4] its Millennium Development Goals of 2000,[5] and its Sustainable Development Goals of 2015[6] codified improved health and development as goals for national governments.

However, the untold story behind these improvements are the efforts of healthcare missionaries and the effect of the introduction of the Biblical worldview on human wellbeing.

These have been instrumental in the improvement of world health,[7] but this key element is often omitted from secular global health literature.

As disciples, our view of global health trends must include not only physical health and development metrics, but also the spiritual health of the ethne [ethnolinguistic groups, commonly known as ‘people groups’]. In an essential 2018 article,[8]

RW Lewis explained the concept of Frontier People Groups (FPGs),[9] a critical refocusing of the concept of Unreached People Groups that had guided frontier missions for 35 years.[10]

Briefly, a FPG is a people group with no known movement to Christ and virtually no known disciples.

As disciples of Jesus, we fulfil his mission through his paradigm, which is a whole-person,[11] whole-household,[12] and all-ethne paradigm.

Examining the intersection of physical, spiritual, emotional, mental, and social health in the ethne lays a foundation for following Jesus’ paradigm.

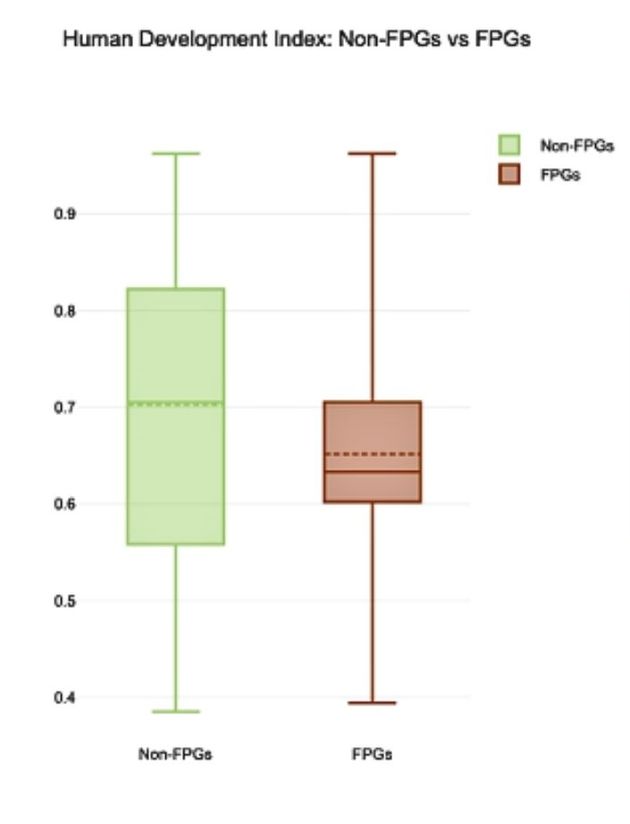

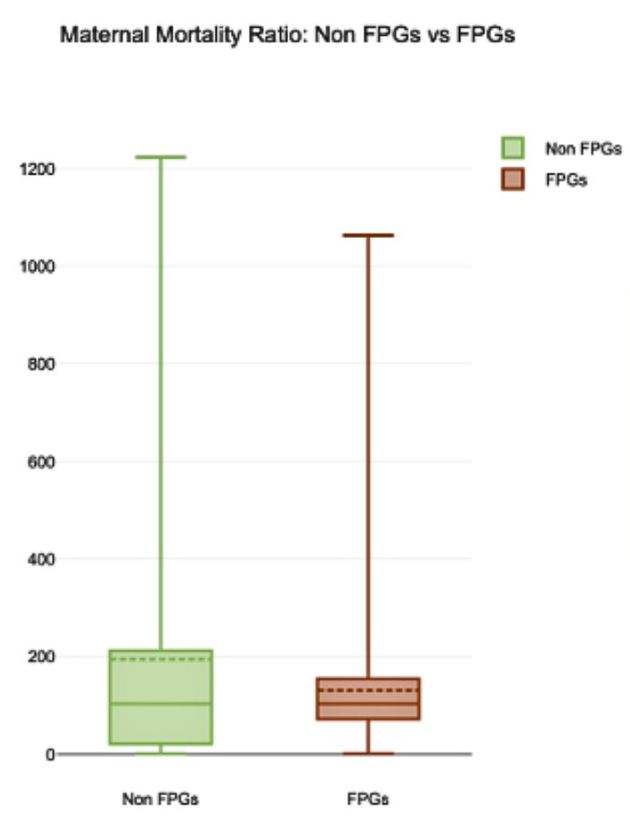

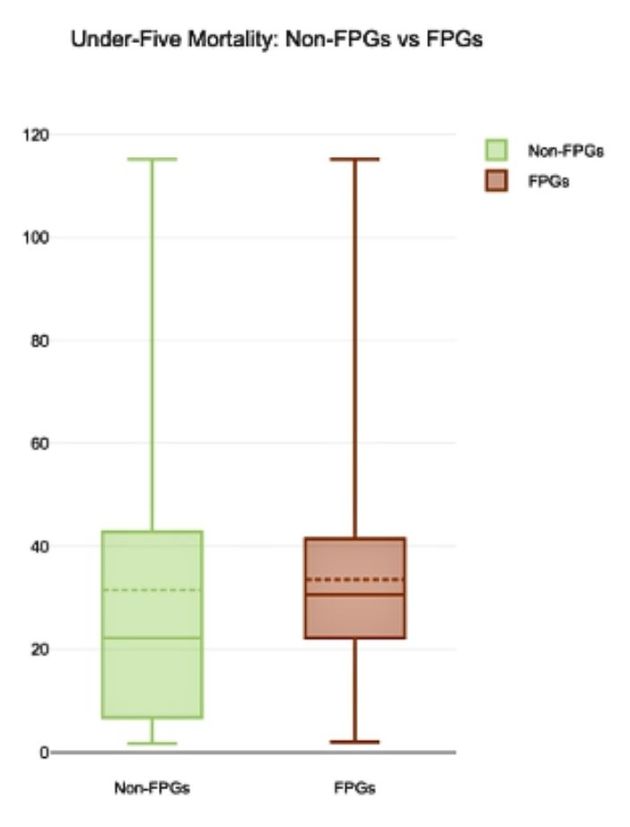

This analysis will focus on the intersection between The Joshua Project People Group Filter[13] was used to create two lists: all non-FPGs and all FPGs.

Human Development Index (HDI),[14] Under-Five Child Mortality (U5M),[15] and Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR)[16] were chosen as health and development indicators. For each people group the country listed by Joshua Project was paired with its corresponding HDI, U5M, and MMR.

For each indicator, a data set was identified for each of the non-FPG and FPG lists. Non-FPGs and FPGs were analyzed and visualized for each of the three indicators using statistics software.[17]

HDI is significantly lower, and U5M is significantly higher, in the FPG group. Because these indicators are at country level and not people group level, it can be said that FPGs are more likely to live in countries with worse HDI and U5M.

MMR is statistically equal between Non-FPGs and FPGs. This may reflect the continued high MMR in many sub-Saharan African countries, where although many people groups have followed Christ, lack of resources, corruption, and instability have continued to hinder perinatal health care.

It may also reflect efforts in India and Bangladesh, which have large numbers of FPGs, but have reduced their MMR to near or below the world average since 2014.[18]

Of note, the median values for each of these health care indicators among FPGs is the same as that of India, which has by far the most FPGs. Of all the FPGs, 72 percent live in South Asia; 36 percent in India.[19]

This data cannot show a causal effect between frontier status in each people group and health or development, but it does demonstrate a relationship at the country level.

It is also limited by development and health data available only for country level, which means that all the people groups in a country are given the same health indicator value, which cannot fully represent the complex reality.

Globalization and diaspora shifts are important realities of today’s world, and Joshua Project reflects this by counting every occurrence of a particular people group in a separate country as a separate people group.

The drawback of this when pairing Joshua Project data with country level data is that comparatively small diaspora groups from the Majority World now living in wealthier Western or Middle Eastern countries, may or may not actually experience the level of health and development that their new country of residence is given in WHO and UNICEF reports.

If these data were weighted by population or by indigenous status, it is possible that the contrast in data would be even more stark.

Despite the limitations, this data reveals another untold story: although FPGs are more likely to live in countries where development and health lag, just as the efforts of Christian workers have been omitted from secular global health literature, physical health and development are often omitted from missiological research that assesses global evangelization progress.

Jesus’ gospel of the kingdom and prayer that God’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven make it crucial that our efforts to reach the remaining FPGs intertwine health and development along with evangelism and discipleship, and that our monitoring of progress assesses metrics of health and development as well as disciples and churches.

Much of the large-scale progress in global physical health in the last 50 years has been made by government health services.

In many countries with large numbers of FPGs, particularly in South Asia and China, most health services are provided by governments.

This progress will likely continue, though progress made by governments is especially sensitive to pandemics, war, and economic downturns.

Traditional healthcare missions have often continued to focus on areas with the greatest physical health needs. Certainly, this glorifies God, magnifies the name and love of Jesus, and can open doors for the gospel.

However, at times this focus on physical needs has been to the detriment of areas and peoples with the greatest spiritual needs—the FPGs.

Traditional healthcare missions have also often focused on technical, institutional solutions such as hospitals, clinics, and large organizations in an attempt to address complex global health challenges.

These solutions are often expensive, highly reliant on technology and foreign involvement, and difficult or impossible to reproduce. This has made it difficult to enter FPGs and enact change in ways that are truly reproducible and sustainable by local disciples.

If these trends continue, healthcare missions will continue to yield the domain of caring for the least of these to secular government health services, which often have no place for the paradigm and love of Jesus.

Within the rise of ‘movement practice’[20] in missions, there has been an encouraging trend in the last 15 years toward whole-person, whole-household, and whole-community outreach.

An important part of these streams includes modelling tangible, sustainable physical outreach and direct prayer for physical needs for seekers and disciples.[21]

The stream of integral mission is further cementing aspects of outreach once divided.[22] As the global missions community continues to embrace ‘movement practice’ and integral mission, this promising trend— reproducible integration of the spiritual and physical—will continue.

Realising that FPGs are generally more likely to live in less-developed contexts with worse physical health and development requires that our outreach to FPGs includes these aspects.

This does not mean that we need to create more development NGOs or build more hospitals or clinics in these areas. These forms of development and healthcare outreach are unwieldy and difficult to sustain and reproduce.

Many of the countries with the most FPGs have relatively developed government healthcare systems. Healthcare missions should look for niches in which the government health system is lacking and continue to shift to incarnational forms of outreach that enter the households of FPGs, particularly in South Asia.

This must be done in ways that emulate Jesus, are reproducible and truly sustainable, and that supplement and augment, rather than compete with, existing government health care entities.

In a city of 200,000 in the Sahel, we and our team combined grassroots health education in homes with Bible storying, prayer for healing, and in-home, relational primary health care.

After four years of doing this with a particular extended family, a small church of baptized disciples was born in a Frontier People Group in which there was no church in that area before.

Those illiterate disciples now reproduce the same oral health and Bible studies in multiple other neighbourhoods and villages. In any setting, disciples can be mobilized to care for their neighbours in tangible ways, regardless of their training or education level.

These efforts should follow the same ‘movement principles’ that God has used to grow movements of disciples all over the world. This will ensure that care for development and physical health proceeds transformationally as part of the whole-person gospel of the kingdom and is reproduced by future generations of lay disciples.[23]

Existing proximate groups or churches of disciples should become hubs of development and health, not necessarily by hiring health professionals or adding dispensaries, but by modelling Jesus’ paradigm of intertwining spiritual, physical, mental, emotional, and social health into disciples’ daily lives, at a level that local disciples can reproduce and sustain.

This will require disciples to rediscover the theme of shalom in the Old Testament and Jesus’ paradigm of whole-person, whole-household care, then to implant these concepts as a crucial part of the gospel of the kingdom to the FPGs.

The final untold story will be recited by Jesus himself. Prior to receiving the praise of all the ethne, he will recite how his disciples in that great assembly cared for the needs of the least of these, many of whom then became their brothers and sisters in that assembly of praise.

Jason Lee (pseudonym) is a disciple of Jesus and a medical doctor. He and his wife, family, and team served for eight years among Muslim frontier people groups in the Sahel of Africa, focusing on movements of disciples, transformational movements of grassroots health education, and in-home relational primary health care.

He is now the Co-Director of Health for All Nations, a ministry of Frontier Ventures. He is also the International Healthcare Catalyst for the largest missions sending organization focused exclusively on Muslims.

This article originally appeared in the January 2024 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis and is published here with permission. To receive this free bimonthly publication from the Lausanne Movement, subscribe online at www.lausanne.org/analysis.

GapMinder, https://www.gapminder.org/tools.

Hans Rosling, ‘The good news of the decade? We’re winning the war against child mortality’, TedX Change September 2010,

Report of the International Conference on Primary Health Care, (September 1978)’, World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund,

‘Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), 19 February 2018’, World Health Organization, ,

‘The Global Health Observatory’, World Health Organization, accessed 9 October 2023,

Gary Bandy and Alan Crouch Ư et al, Building from Common Foundations: The World Health Organization and Faith-Based Organizations in Primary Healthcare, World Health Organization (2008): 5, 9-12.

RW Lewis, ‘Losing Sight of the Frontier Mission Task’, International Journal of Frontier Missiology 35, no. 1 (Spring 2018): 6.

RW Lewis, ‘Clarifying the Remaining Frontier Mission Task’, International Journal of Frontier Missiology 35, no. 4 (Winter 2018): 155-168.

Dave Datema, ‘Defining ‘Unreached’: A Short History’, International Journal of Frontier Missiology 33, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 45-71.

Jesus continually held in balance addressing the physical and spiritual state, as well as the emotional and social, of those with whom he interacted. See Matt 6:10-13, Mark 5, Luke 5:17-26, Luke 8:43-48, Luke 10:8-9

T&B Lewis, ‘As For Me and My House: The Family in the Purposes of God’, Mission Frontiers 34, no. 2 (March-April 2012): 6-10.

‘People Group Filter’, Joshua Project, accessed 9 October 2023, https://www.joshuaproject.net/filter.

‘Human Development Report’, United Nations Development Programme, accessed 9 October 2023,. The Human Development Index (HDI) includes life expectancy at birth, mean years of schooling for adults and expected years of schooling, and the gross national income per capita. A higher HDI means better development. This report gives 2021 data as the most recently available.

‘Under-Five Mortality Data, January 2023’, UNICEF, accessed 9 October 2023, . The Under-Five Mortality Rate (U5M) is the probability a newborn would die before reaching exactly 5 years of age, expressed per 1,000 live births. A higher U5M means more deaths. This report gives 2021 data as the most recently available.

‘Trends in Estimates of Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) and Lifetime Risk of Maternal Death, 2000-2020, May 2023’, UNICEF, accessed 9 October 2023,. The Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) is expressed as maternal deaths during, or within 42 days after, pregnancy per 100,000 live births. A higher MMR means more deaths. This report gives 2020 data as the most recently available.

‘Statistics Online’, Statistics Kingdom

Max Roser and Hannah Ritchie, ‘Maternal Mortality’, Our World in Data,

RW Lewis, ‘Clarifying the Remaining Frontier Mission Task’, International Journal of Frontier Missiology 35, no. 4 (Winter 2018): 160-162.

‘Movement practice’ here includes the various streams of missions practice that pursue people movements to Christ: variously referred to as people movements, Christward movements, church-planting movements, disciple-making movements, vibrant communities of Jesus-followers, etc.

David Trousdale, Miraculous Movements (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2012), 58-59, 83-88, 184, 188-189.

David Greenlee, Mark Galpin, and Paul Bendor-Samuel, eds. Undivided Witness: Jesus Followers, Community Development, and Least-Reached Communities (Oxford: Regnum, 2020).

Andrea C Waldorf, ‘Community Development and the Formation of Vibrant Communities of Jesus Followers: Shared Principles of Excellence’, International Journal of Frontier Missiology 37, no. 2 (Summer 2020): 93-98.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.