Modern and post-modern perspectives held by (often) biblically-illiterate and spiritually tone-deaf art critics and curators ignore the gospel message of Rembrandt and Van Gogh.

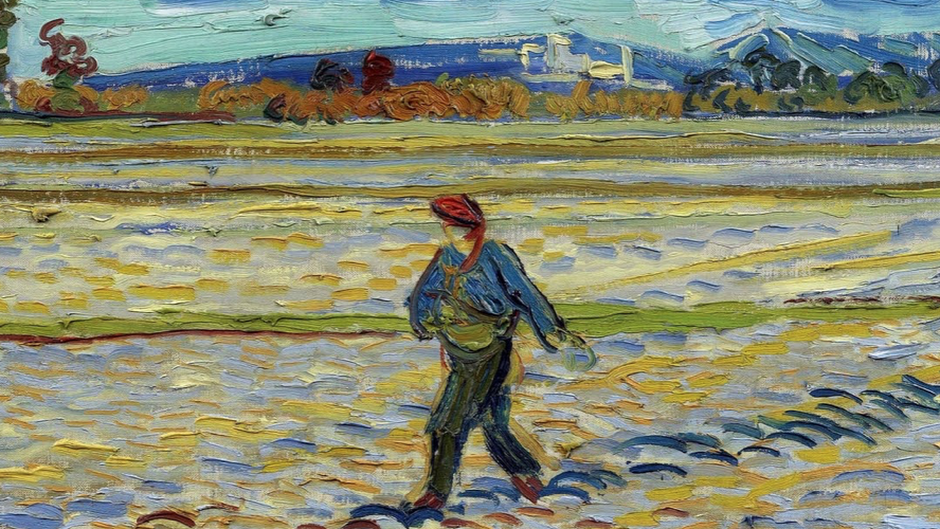

A reproduction of The Sower, of Vincent Van Gogh.

A reproduction of The Sower, of Vincent Van Gogh.

Last weekend the church my wife Romkje and I attend, the Noorderkerk, celebrated 400 years of Christian presence in the city of Amsterdam, with concerts, tours, exhibits and a mayoral visit, among other activities.

On Easter 1623, fifty-five years after the city chose to become Protestant, the doors of the Noorderkerk opened to its largely migrant neighbourhood. It was the first church in the city with a specific Protestant architecture, projecting the pulpit more into the centre of the congregation to emphasise the centrality of God’s Word.

Eight years later a young artist named Rembrandt van Rijn moved to the city from Leiden to make his name. Whether or not he ever attended this church, we don’t really know. But his curiosity about the church’s architectural novelty most likely would have drawn him there sometime. During his career in the city he produced over 800 paintings, drawings and etchings based on the Bible, many featuring Jesus.

Over 250 years later, another young man named Vincent van Gogh arrived in the city hoping to study theology. Unlike Rembrandt, we know much about his visits to the Noorderkerk. He wrote detailed descriptions in his letters to his brother Theo, including of the first church service he attended in the city, the 7am Sunday service in the Noorderkerk. This became a pattern for him during his student days. He would then attend other services elsewhere, before teaching bible to street kids in a city mission.

Although van Gogh had worked in his uncle’s art shop, he had no ambition at that stage to become an artist himself. He wanted to become a preacher like his father and sow the Word of God. One of the first sermons he heard in the Noorderkerk was about the parable of the sower. Deeply impressed, Vincent would later make more than thirty etches and paintings on the subject.

Yet even then he saw everything with the eye of an artist. He told Theo how the preacher ‘painted as it were…with the feeling of an artist in the true sense of the word’.

‘This morning I saw in the church an old lady,’ he continued, ‘who reminded me so much of that etching by Rembrandt, a woman who has been reading in the Bible, and has fallen asleep with her head leaning on her hand….’

Yet his hope to become a preacher was never fulfilled. He sojourned for some 400 days in the city as a student, 1877-78, before moving on to Belgium to work as an evangelist among coal miners. Further failure and rejection there eventually led in 1880 to his decision to become an artist.

Unlike Rembrandt, whose work began to fascinate and inspire him while living in Amsterdam, Vincent would never enjoy any recognition or fame during his short lifetime. He only ever sold one painting! While he never lived in Amsterdam as an artist, one of the city’s biggest tourist attractions today is a museum displaying many of his 900 paintings and drawings. Also unlike Rembrandt, the bulk of whose work was created in Amsterdam, Vincent’s only work in the city were two quick sketch paintings of scenes a few hundred metres from the Noorderkerk.

Currently a spectacular 360-degree audio-visual experience tells how Vincent’s work was influenced by the older master, cast by 36 projectors onto the Noorderkerk’s centuries-old walls and ceiling. Visitors can watch Vincent meets Rembrandt from the pews or lie on bean bags on the floor, listening to the English-language commentary in van Gogh’s own words.

For the 400-year commemorations of the Noorderkerk, I was invited to create an exhibition exploring the unlikely relationship of these two world-famous painters with this artistically sober, typically Calvinistic, sanctuary. This in turn led to opportunities to talk with visitors about the relationship both these painters had with One their art speaks of as the true Master.

Modern and post-modern perspectives held by (often) biblically-illiterate and spiritually tone-deaf art critics and curators ignore this message of these two Dutch masters. The secular narrative would have Vincent reject Christianity as he reinvents himself as an artist. Yet as Anton Wessels, emeritus professor of religion, argues in ‘A Kind of Bible; Vincent van Gogh as evangelist’, while van Gogh did break with the institutional Christianity of his father, he continued to be an evangelist in his own distinctive way.

Late in his life, he wrote about Jesus ‘as a greater artist than any other; for he despised marble, clay, and the palette, and worked upon living flesh. That is to say, … he created real living people, immortals.’

This is a story we plan to unfold next month with an expanded exhibition in Look Up, the YWAM bookstore/art gallery/information centre in the heart of Amsterdam, on the theme: Vincent and Rembrandt meet Jesus.

Jeff Fountain, Director of the Schuman Centre for European Studies. This article was first published on the author's blog, Weekly Word.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o