In Europe, we have become used to the arrival of asylum seekers and refugees, most notably when some 2 million people fleeing the conflicts in Syria and Afghanistan. Yet the Ukraine migration crisis has been different.

![Families leaving Ukraine after the Russian invasion. / Photo: [link]Kevin Bückert[/link], Unsplash, CC0.](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/636bbfeeb3e7e_kevin-buckert-fKf9bmZUSmA-unsplashCropped.jpg) Families leaving Ukraine after the Russian invasion. / Photo: [link]Kevin Bückert[/link], Unsplash, CC0.

Families leaving Ukraine after the Russian invasion. / Photo: [link]Kevin Bückert[/link], Unsplash, CC0.

Mapping migration in Europe has been a regular theme in Vista Journal. We have dedicated several editions to migration issues from a number of different perspectives for migration is, arguably, the most important missiological reality for the church in Europe today.

The arrival of millions of Christians from the Majority World over the last 50 years has changed the face of the church in Europe. Yet the Ukraine war and subsequent migrant crisis has changed Europe again, for it has resulted in the largest migration of refugees within Europe since World War II: more than 7.5 million refugees have fled to other European countries as of the end of September 2022.[1]

This article seeks to provide a statistical description of the dimensions of the Ukraine War and migrant crisis, and to briefly discuss its impact on mission in Europe.

We have become used to the arrival of asylum seekers and refugees over the last few decades, most notably in 2015/16 when some two million people fleeing the conflicts in Syria and Afghanistan made their way to Europe by land and sea.

Yet the Ukraine migration crisis has been different to these situations in a number of ways.

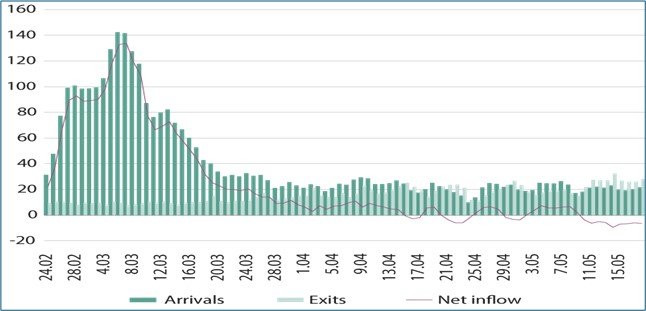

Firstly, it was different in its speed. The graphic below shows the daily border traffic from Ukraine into Poland in the first weeks following the Russian invasion in February 2022 [2]. Within just a few days, more than a hundred thousand people a day were crossing the border into Poland, and in the first two months, that number totalled around 3.5 million. Poland took the brunt of this first wave of refugees but many others fled into the other neighbouring countries. The appearance of refugee camps across Central and Eastern Europe encouraged countries in Western Europe and further afield to open their doors to host refugees

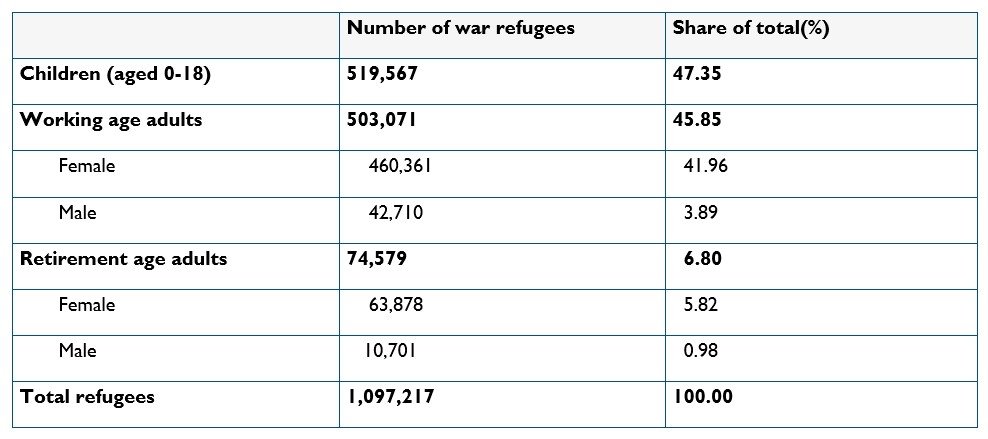

[photo_footer] Daily border traffic (in thousands) between Ukraine and Poland, 24 Feb.- 19 May 2022 [/photo_footer] Secondly, the Ukraine refugee crisis was different in its demographic makeup. As can be seen from the table below, the vast majority of the Ukrainian refugees were women and children. This was evident from the very earliest days and may have influenced the willingness of many nations to host them on a temporary basis, but it also made them particularly vulnerable to exploitation.

[photo_footer] Demographic structure of war refugees in Poland. [/photo_footer]

The UN Operational Data Portal records 7,536,433 refugees from Ukraine reported across Europe, 4,183,841 of whom have registered for Temporary Protection Schemes or similar.

Around 2.5 million of the remainder are estimated to have fled or been forcibly transported into Russia.

Yet these numbers do not include the 7 million Internally Displaced People (IDPs) which the International Organisation for Migration estimate to be in Ukraine as of the end of August 20223. We should remember that this conflict did not begin in February 2022, but rather with the commencement of hostilities in 2014, and many Ukrainians have been living as IDPs in Central and particularly Western Ukraine for some years. Nevertheless, on the basis of a pre-conflict national population of 44 million, the salient truth is that roughly one in three Ukrainians have been forced from their homes as a result of the conflict.

Whilst governments across Europe made early arrangements to provide Ukrainian nationals with temporary protection, the fate of Third Country Nationals (TCNs) caught in Ukraine was more problematic. In June 2022, the International Organisation for Migration conducted a survey among TCNs who fled the war into Germany. According to official figures, around 18,000 TCNs from Ukraine had sought temporary protection in Germany since February 2022. Though the survey sample was small (just 114 respondents) the results suggest that the TCNs seeking refuge in Germany were overwhelmingly young African men who were studying in Ukraine when war broke out [3].

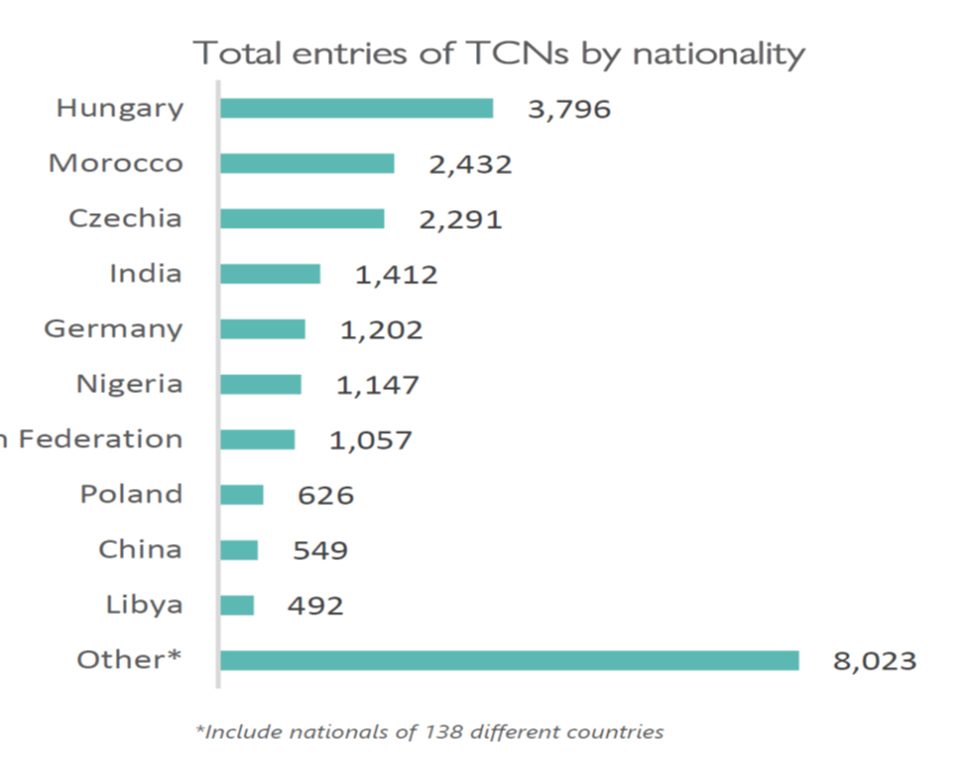

More reliable perhaps is the picture that emerges from another IOM study in Slovakia [4] . During the first two months of the conflict, this survey found that of the 360,498 people registered at entry, 332,587 (92%) were Ukrainians, 4,884 (1%) were Slovaks, and 23,027 (7%) were TCNs. Of these, 10,483 then exited the country for other destinations.

The top ten nationalities of TCNs entering were Hungarians, Moroccans, Czechs, Indians, Germans, Nigerians, Russians, Poles, Chinese and Libyans, though as indicated below, almost all the Hungarians, Czechs, Germans and Poles then exited, leaving many non-European TCNs stranded in these countries. Their legal status continues to be an issue.

[photo_footer] Numbers of Third Country Nationals by Nationality entering and subsequently leaving countries bordering Ukraine. [/photo_footer]

Finally, we cannot ignore that the Ukraine refugee crisis has provided an opportunity for people traffickers and others who wish to exploit victims for other purposes, not least because the refugees are predominantly women and children. A recent report describes abusive and exploitative situations both inside Ukraine and at the borders [5]. Even prior to the conflict, Ukrainians were identified as having been trafficked into many different countries. This is likely to have increased significantly this year. Even more troublingly, the aforementioned TCNs may need to resort to people smugglers in order to get out of the legal limbo in which they find themselves. The Moroccans, Indians, Nigerians, Chinese, Libyans in the above chart may be particularly vulnerable.

The scale of the Ukraine war and refugee crisis is unprecedented in the experience of most Europeans. This article has focused on the statistics of the war. However, behind every statistic is a person, a life and a story - and in this case, millions of individual people, lives and stories, each with hopes, dreams and fears (and each one precious to God).

The response from churches from across Europe has been extraordinary. Thousands of churches and Christian families have opened their doors to receive Ukrainian refugees. As described elsewhere in this edition of Vista, in every nation organisations have emerged to take the lead in the local response, and transnational platforms have emerged to connect and coordinate initiatives. These connections may have long-lasting consequences for mission in Europe.

For the last 30 years, Ukraine has had one of the most dynamic mission movements in Eastern Europe. Thousands of Ukrainian missionaries were mobilised and sent into Russia, the Central Asian Republics, and into Europe. Now many others have been forced to leave by the war and find themselves spread across Western Europe. Every Christian migrant is a potential missionary and these Ukrainian Christians can be a huge blessing to those who are receiving them.

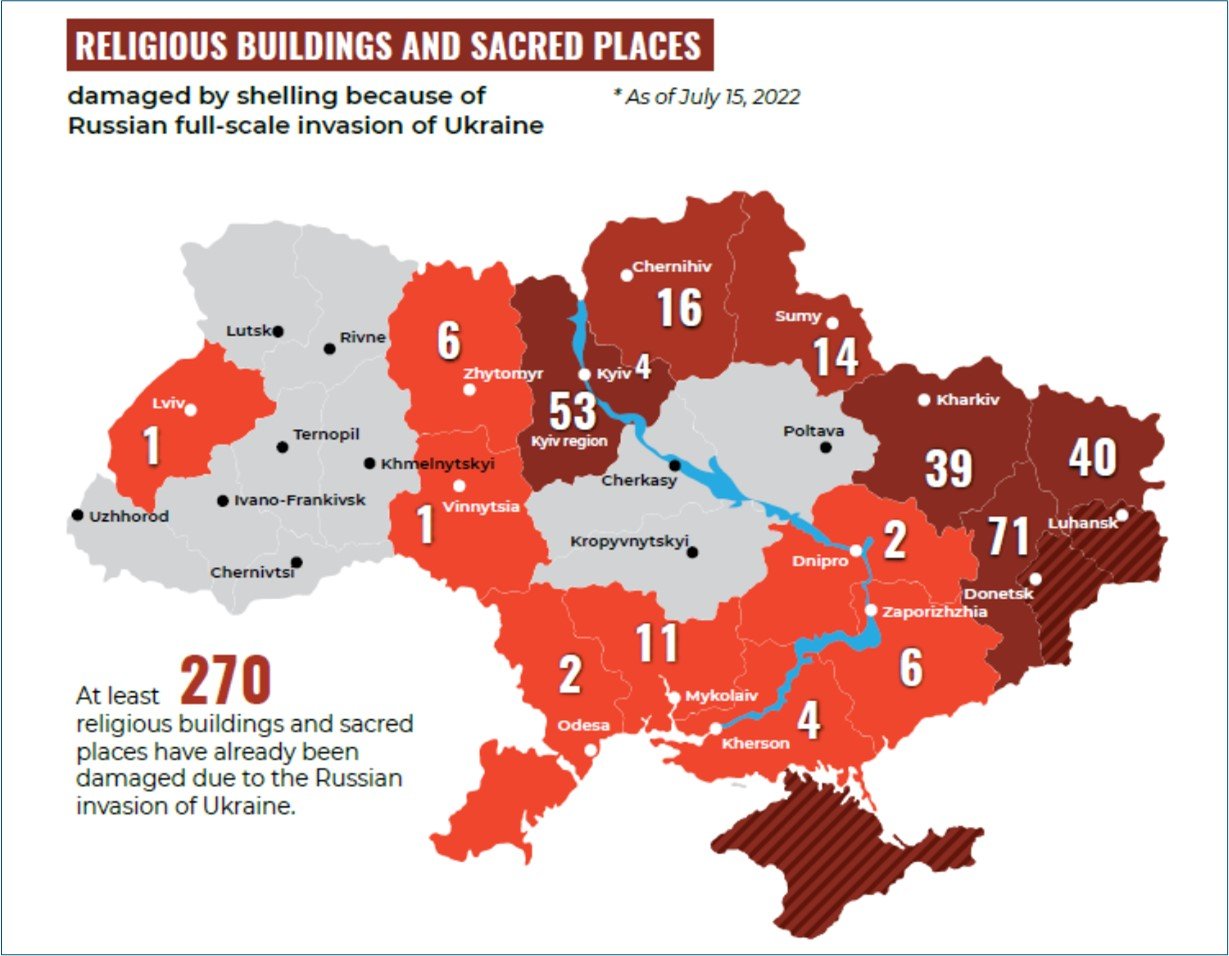

However, we should not diminish the impact that this barbaric war has had on the refugees and on those who have remained in Ukraine. Many are grieving and traumatised and need our care and support. And in Ukraine itself, millions remain under the threat of Russian bombardment or worse. A recent study by the Institute for Religious Freedom found that at least 270 religious buildings, educational institutions and sacred sites had been damaged or destroyed [6]. These were concentrated in the regions of Donetsk (71), Kyiv (53), Luhansk (40 and Kharkiv (39).

There is also evidence of pastors and other religious leaders being detained or killed by Russian troops. Yet stories are also emerging of churches that now have three services every Sunday rather than one as they did back in February, such is the hunger for God’s word. There is devastation and fear but there is also faith. Could the breadbasket of Europe become the basket from which the bread of life is spread in Ukraine and across the whole of Europe?

Jim Memory, the Regional Director of Lausanne Europe and a founding editor of Vista.

This article was first published in the Vista Journal number 42 (November 2022) and re-published with permission.

1 UNHCR Operational Data Portal, Ukraine Refugee Situation. Link, Accessed 1st October 2022

2. Duszczyk and Kaczmarczyk, “The War in Ukraine and Migration to Poland: Outlook and Challenges”, Intereconomics, 2022, Number 3. Link.

3. International Organization for Migration, Ukraine Internal Displacement Report, 23 Aug 2022. Link.

4. International Organisation for Migration, IOM Germany – Third Country Nationals arriving from Ukraine in Germany, June 2022. Link.

5. International Organisation for Migration, IOM Slovakia – Displacement Analysis of Third Country Nationals, April 2022.

6. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Conflict in Ukraine: Key Evidence on Risks of Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants, August 2022. Link.

7. Institute for Religious Freedom, Russian Attacks on Religious Freedom in Ukraine, September 2022. Link.

photograph credit: mvs.gov.ua

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.