Roles,strategies and reflections for outsiders in local contexts. An article by Kirst Rievan.

![Image via [link]Lausanne Movement[/link].](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/60f17fb77d41d_lgaforeigners.jpg) Image via [link]Lausanne Movement[/link].

Image via [link]Lausanne Movement[/link].

At a recent Zoom prayer meeting, I met Sylvia.1 She had been heading to Asia as a long-term missionary, but was now in COVID lockdown in Europe.

She was discouraged and wondering if she would ever get to Asia.

The ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement had also prompted friends to question the appropriateness of her as a Westerner going to Asia.

‘Lord, is there still a role for outsiders in mission?’

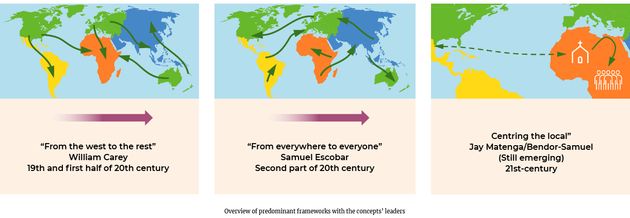

Over time, mission has operated within different frameworks. Probably the best-known one is captured in the phrase: ‘From the West to the rest’.

This framework was already challenged in the mid-1800s by the three-self formula which promoted the establishment of churches that would be self-governing, self-propagating, and self-supporting.

It became a major topic at the conferences of the World Council of Churches (WCC) in the twentieth century, and came to a head with the call in 1971 from Bishop John Gatu of the Presbyterian Church of East Africa, who said, ‘Missionaries go home!’

This did not take root in the evangelical mission movement, but several years later, Escobar’s phrase, ‘from everywhere to everyone’, challenged the ‘West to the rest’ paradigm, reflecting the fact that the epicentre of the global church had moved from the West to the majority world. 2

An alternative framework is now emerging which puts the onus on the local, indigenous church. Jay Matenga, director of the Mission Commission of the World Evangelical Alliance, promotes ‘centring the local’. 3

Paul Bendor-Samuel, Executive Director of the Oxford Centre for Mission Studies, talks about the increased need for ‘indigenous witness’.4

They both assert that the leadership of local mission efforts should be local, with outsiders in a supporting role, a principle which is not new, but which is being accelerated by the COVID pandemic.5

These three frameworks still co-exist and overlap, but my sense is that, historically, they have dominated in the order shown.

The foundation for moving beyond one’s community was laid by Jesus himself: ‘Go and make all people my disciples.’ Acts 1:8 encourages the disciples to start nearby (Jerusalem), but then expand to the ‘ends of the earth.’ Paul lived this out as a cross-cultural worker, going from country to country, preaching the Word.

But such a claim might be too simplistic for the modern era. In New Testament times, churches were few, while now believers exist in nearly every nation. In several cases, Paul handed over responsibilities very quickly to local church leaders, while he as outsider, moved on to new places.

At the same time, in some places (eg Rome) Paul still felt it necessary to visit and preach himself, despite the existence of a church. In the Bible it does not seem to be an either/or but a both/and; a role for both the outsider (Paul) and the local Christians.

The centrality of the local church is not a new concept. Goldsmith testifies that, in the 1960s, when he wanted to work among the Karo Batak, the local believers were so disgruntled with the colonial attitude of the Dutch missionaries that they made these stipulations:

1) No financial contributions to the ministry of the church beyond regular Sunday collections; 2) No separate expat housing; 3) No speaking or outreach activities unless invited by the church. 6

The Goldsmiths accepted these conditions and the resulting challenges and fruit. It required a totally different mindset for both expats and the community.

The more I talk with colleagues and partners about the role of expats, the more convinced I become that it is not about a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ regarding outside involvement in missions, but rather the attitudes and roles the outsider plays.

It may help to consider it as shifts in identity, from:

‘actor’ to ‘facilitator’

‘initiator’ to ‘catalyst’

‘family-head’ to ‘guest’

‘hero’ to ‘enabler’.

Some of this is related to timing and the maturity of the local church, but the shift reflects a basic posture. When recruiters ask what type of workers are needed, I now add: ‘People who deeply enjoy making others successful!’ Those who come with that passion fit well into the new mission paradigm.

Are there no situations where the outsider needs to take the initiative, lead the way, and take action?

In the October–December 2020 issue of the Evangelical Missions Quarterly, the people-groups approach to mission was discussed: ‘When churches or agencies prioritize partnering with national churches/believers, fields with no believers are inadvertently excluded.’ 7

That is a valid point and touches on the heart of mission. Within the Bible translation movement, the phrase ‘the most local expression of the church’ has been introduced to acknowledge that, in many people groups, the church is not yet present, but there might be a network of churches in the region, a local mission, or a Christian development organization with which we could partner.

One of my early mentors once got me on the edge of my seat by stating: ‘You should never hand over a project to the local community.’ That seemed so wrong to me! But it turned out that there was a comma, not a full-stop as she continued her sentence, ‘. . . . because it should have been theirs from the beginning.’

So true, but also so difficult in practice! Let me give a few examples of roles and strategies, which aim to reduce the roles of outsiders.

Local-leadership approach —The outsider comes at the invitation of a local church or agency. Local leaders set the terms and conditions, and the outsider reports to them. I have seen this working well in places where there is a relatively strong church presence in the region.

Anchor-project approach —The outsider is initially assigned to a people group to gain in-depth experience and/or get things started, and gradually moves to a role at a regional level. I have seen that successfully applied in Bible translation ministries and unreached people-group ministry.8

Short-term approach —The short-termer functions under local leadership as part of a wider mission program and is guided by experienced workers. I have seen that works well, with good orientation and when there is someone on the ground with the vision and skillset to make short-termers successful.

Remote approach —In this case, the outsider has an advisory, consulting, or training role and is physically based at a significant distance from the program’s location. For ministries that are technical in nature, this can work well through online technology.9

Workplace approach —The outsider has a professional role in the society working within a local job framework. The workplace environment is used to witness. From what I have seen, it is important that such missionaries are strongly connected with a fellowship of people with the same vision. 10

Umoja — The outsiders mobilize and equip the local church to engage in social development of their community, but the actor is the local church. Tearfund and its partner organizations have seen good results in several African and Asian countries. 11

Movement approach — The role of the outsider is mainly a catalyst. Activities are set up that multiply themselves without requiring the influx of money and infrastructure. It has reportedly been successfully applied in church-planting ministry in India and other places.

Common Framework for Bible translation — The framework consists of a set of principles embraced by a large group of Bible translation organizations. It limits the role of outsiders to resourcing and equipping, while the implementation is done by ‘the most local expression of the church’. 12

Each of these approaches has its critics, but, when we focus on the basic principles, they can help us shape our ministry in a less outsider-centred way, while still staying faithful to our mission.

When I recently talked with national leaders about the role of expats, they said that they were puzzled by the statements foreigners make with regard to their serving role, while still continuing to initiate new plans and programs.

It shows how complicated the issue is. We could start by reflecting personally on some basic questions:

What are my motives for being in my present role? I realize that usually I have a mixture of motives. ‘Search my heart, O Lord, and see that love for you and the people is still my driving force.’

Are there elements in my ministry where I am an obstacle to my local brothers and sisters taking initiative and leading? Is there something I need to stop doing?

Here are questions I ask myself as a leader in my organization: 13

What is the missiological basis for how and whom we recruit? How does our missiology influence the shaping of assignments?

Is the amount of energy, time, and money we spend on recruiting, assigning, supervising, and caring for our different types of staff in balance with our values?

Are the people and partners presently involved in the shaping of assignments for staff the right ones? Is there sufficient local voice?

So, what would I tell Sylvia? I would read Luke 10 with her: ‘The harvest is plentiful but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field’.

We would together pray for more workers—people from within the community, cross-cultural workers from within the country, and people from across the globe.

I would encourage her to join the workforce, have fellowship with her co-workers, be accountable to local leadership, and look for every opportunity to enrich the ministry by making it globally connected and to strive to make others successful!

Kirst Rievan (pseudonym) and his wife are from Europe and have been living in Asia for over 20 years. Kirst provides leadership in Asia and Pacific for a global, faith-based development organization.

Kirst considers himself a 'reflective practitioner', a fellow-learner, not an expert. Kirst has a doctorate in missiology from BIOLA University.

This article originally appeared in the July 2021 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis and is published here with permission. To receive this free bimonthly publication from the Lausanne Movement, subscribe online at www.lausanne.org/analysis.

1. Sylvia is a fictional composite character based on real people.

2. Editor’s note: See article by Allen Yeh entitled, ‘The Future of Mission is From Everyone to Everywhere’, in the January 2018 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis,

3. Jay Matenga, ‘Centring The Local’, a seminar originally presented at the Wycliffe Global Alliance/SIL ‘Together in Christ 2021’ conference,

4. Paul Bendor-Samuel, ‘Covid-19, Trends in Global Mission, and Participation in Faithful Witness’, Transformation 37 (4):255–265,.

5. Editor’s note: See article by Joseph W. Handley entitled, ‘Polycentrism as the New Leadership Paradigm’, in May 2021 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis,

6. Martin Goldsmith, Get a Grip on Mission: The Challenge of a Changing World (Leicester, United Kingdom: IVP, 2006).

7. Rebecca W Lewis, ‘Fog in the Pews: Factors behind the Fading Vision for Unreached Peoples’, Evangelical Missions Quarterly 56 (4),

8. A concise description of this approach is given in Anchor Project Approach to Assignments.

9. Michael P. Greed, ‘The Changing Face of World Mission and the Role of the Western Worker in it’, Academia, May 2019,

10. Operation Mobilization, the Lausanne Movement, and other organizations are giving this increased attention. See, for example, the Lausanne Workplace Ministry site,

11. Umoja Facilitators’ and Coordinators’ Guides can be downloaded from,

12. See this one-page summary of the Common Framework for Bible translation

13. For questions related to the practices and structures of organization, see article by Kirst Rievan entitled, ‘Uncovering Discrimination in Missions’, in January 2021 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis,

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o