The terrorist group controls a large part of the Horn of Africa. Its obsession for imposing Sharia law has significantly worsened the situation of Christians.

![Al-Shabab militants in Baraawe. The organisation has between 7,000 and 12,000 soldiers. / [link]Radio al-Andalus [/link], Wikimedia Commons.](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/66d99991ada3d_somayiha.jpg) Al-Shabab militants in Baraawe. The organisation has between 7,000 and 12,000 soldiers. / [link]Radio al-Andalus [/link], Wikimedia Commons.

Al-Shabab militants in Baraawe. The organisation has between 7,000 and 12,000 soldiers. / [link]Radio al-Andalus [/link], Wikimedia Commons.

Eighteen years have passed since 2006, when a group of radicals in Somalia influenced the regional courts with Sharia law and founded the paramilitary group Harakat Al-Shabab.

Since then, the jihadist organisation has gone through a journey of victories and defeats, like other jihadist groups. However, what is striking to international analysts is its good 'health'.

Although the group somewhat went international by joining the Al-Qaeda network in 2012, it has remained one of the few jihadist groups focused on its particular fight with national and regional authorities, acting also in bordering countries, such as Kenya.

This, so far, makes them more durable than other cross-border organisations, such as Al-Qaeda itself or the self-proclaimed Islamic State.

Al-Shabab still has between 7,000 and 12,000 militia members, according to specialist on the Horn of Africa region Stig Jarle Hansen in an article for The Conversation.

Hansen argues that al-Shabab's survival is due to six factors.

The first has to do with the failure of the West in the country and the region.

The failed presence of the United States and the United Nations, which withdrew in 1994, was followed by an unstable state and the urgency caused by a famine that was affecting more and more of the population.

In its narrative, Al-Shabab has been able to remind Somalis that the democratic institutions created by the West are fallible and do not provide the security that the local population needs.

This speech has given Al-Shabab two important assets, according to Hansen, which are two other key aspects.

One is protection. By controlling vast areas of territory, the terrorists have gained, in part, the favour of a population in need of protection.

The other factor, the communal and ethnic conflicts, has reaffirmed the position of the jihadist organisation as a strong actor.

Although the Somali government has repeatedly called on the various ethnic communities to unite in the fight against jihadism, it has not been very successful, allowing the radical Islamists to keep their control amidst territorial and social fragmentation.

Another factor is illegal funding. Like other jihadist groups, Al-Shabab has built a network of illegal tax collection and money laundering that has enabled it to fund much of its infrastructure.

Smuggling and other actions have also contributed to the economy of the group.

Furthermore, Hansen mentions the weakness of the Somali army and the safe haven that the jihadists have found in the middle and lower Juba area in southern Somalia, as well as in the south-western region, where they hold control for over 15 years and have developed a well-established administrative structure.

The Armed Conflict Location and Events Data (ACLED) project reported in June that the government had recovered some strategic locations in the area.

Although some wonder why it is not possible to fight Al-Shabab through an international coalition, as it was done, for example, with the self-proclaimed Islamic State, the historical particularities of the conflict in Somalia and the failure of the West in the country limit that possibility.

Moreover, jihadism has shifted from operating mainly in the Middle East to Africa to concentrate its strength after the failure of Da'esh.

The United Nations Security Council has just renewed the mandate of the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) until the end of the year, so that the over 12,626 military personnel on Somali soil will remain in the country until at least 31 December 2024.

ATMIS has also agreed on a regional security initiative in partnership with Djibouti, Kenya and Ethiopia focused exclusively on combating the jihadist group.

According to Hansen, these steps come in a period of stagnation caused by the failure of both Western and locally organised counter-offensives.

In recent weeks, however, the Somali government has claimed to kill at least eighty al-Shabab members in response to an attack by the jihadists on three towns that had recently been recovered from their control by the authorities.

Al-Shabab's story has greatly contributed to the worsening situation of Christians in Somalia.

The country has been ranked the second most hostile place in the world for Christians by the organisation Open Doors in the last two editions of its World Watch List.

"Church life in Somalia is non-existent, and in recent years the dangers faced by Christians appear to have worsened", says the organisation.

In 2021, Spanish news website Protestante Digital spoke to two Christians in Somalia who are responsible for a group of believers connected through Facebook.

"Most Somali Christians are underground believers. We are a persecuted community", said Abdi Duale and Kawser Omar.

Beyond Al-Shabab activity, there are other factors that worsen the situation of the Christian population.

The official authorities have also failed to show a plan of action to protect the religious diversity of the country. In 2022, the government appointed Mukhtar Robow, a former Al-Shabab No. 2, as Minister of Religious Affairs.

Even in family and personal relationships, Christians are often marginalised and harassed in a largely Muslim and conservative society.

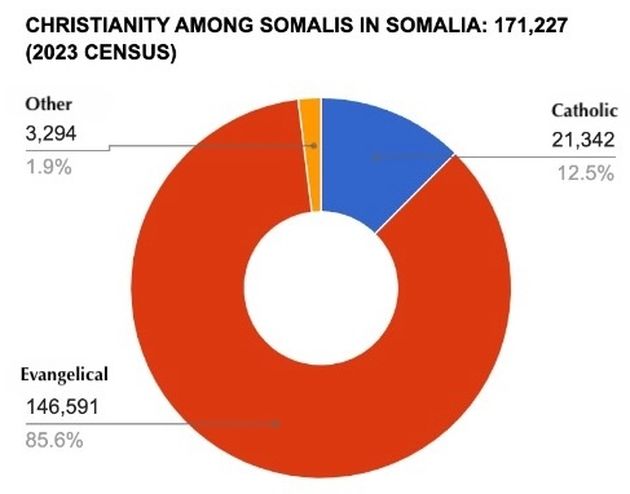

Although it is difficult to know exactly how many Christians are in Somalia, the Bible Society of Somalia has recently published that there are over 171,000 Somalis who identify themselves as Christians in the country, 85.6% of whom are evangelicals and 12.5% Catholics.

To those would be added another 7,642 Christians in the breakaway region of Somaliland, with 52% Catholics and 42.1% Evangelicals, in addition to about 6% who identify with other branches of Christianity.

According to the Bible Society of Somalia, there are also Christians among Somalis who have migrated to surrounding countries. They report 5,649 in Kenya, 8,917 in Ethiopia and 3,760 in Djibouti.

[analysis]

[title]One more year[/title]

[photo][/photo]

[text]At Evangelical Focus, we have a sustainability challenge ahead. We invite you to join those across Europe and beyond who are committed with our mission. Together, we will ensure the continuity of Evangelical Focus and Protestante Digital (Spanish) in 2024.

Learn all about our #OneMoreYearEF campaign here (English).

[/text][/analysis]

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.