In the Louvre Museum, Paris, there are several objects that will provide an interesting approach to biblical archaeology.

If someone is interested in knowing what evidence of biblical events archeology can provide, he would love to know that in the Louvre Museum, Paris, there are several objects that will provide an interesting starting point.

In this case we will focus on a limestone stele that commemorates a battle between the Sumerian kings Lagash and Umma, which took place approximately in 2450 BC.

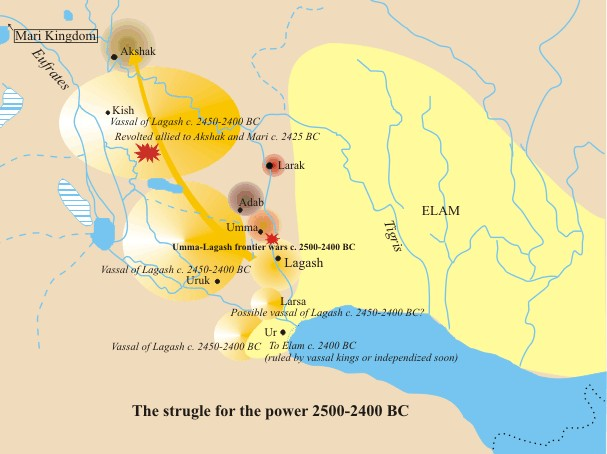

It is framed within the end of the archaic period and the beginning of the classical period. We find samples in 4 cities: Ur, Kis, Umma and Lagash, and which we place between 2990 and 2330 BC.

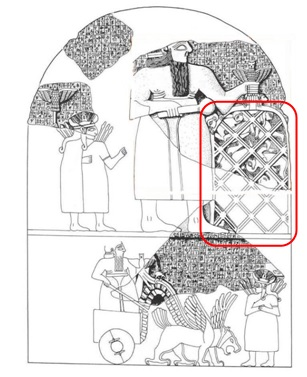

There are 7 fragments of this stele sculpted on both sides, which measured 180cm high, 130cm wide and 11cm deep, when it was complete. These show a low figurative relief that tells a battle and is divided into 2 horizontal records. On the top of one of the sides, we find a row of soldiers properly equipped with shields and spears. They are structured in phalanx formation, all of the same size, disposed behind King Eannatum, who is riding a cart and holds in his right hand a curved weapon formed by 3 metal bars joined together by rings. In this scene, the soldiers pass over the corpses of the army of the city of Umma, which they just defeated. While in the lower engraving, we find a series of soldiers placed diagonally and also armed with spears, which walk after their king.

In the illustration, the fishing net can be seen on the right side, held by the king.

In the illustration, the fishing net can be seen on the right side, held by the king.On the back of the stele appears an image of the warlike god Ninurta or Ningirsu, protector of the city of Lagash. He was worshiped as a warrior and demon eliminator god, as well as a hurricane god. In this stele, this god appears sculpted celebrating the capture of the inhabitants of Umma in a large fishing net.

And it is at this point that the story of this battle takes us to the first chapter of the book of the prophet Habakkuk, in verses 15 to 17, where we read the following:

He brings all of them up with a hook;

he drags them out with his net;

he gathers them in his dragnet;

so he rejoices and is glad.

Therefore he sacrifices to his net

and makes offerings to his dragnet;

for by them he lives in luxury,

and his food is rich.

Is he then to keep on emptying his net

and mercilessly killing nations forever?

In this text, the prophet is comparing the Chaldeans, also known as Babylonians, with a great fisherman. Habakkuk says that YHVH allows the empire to take whatever people he wants, and does not conceive how his God lets Babylon show off his weapons of conquest and his victories before his gods.

The key thing is that the figure of the net, both represented in the stele and used by Habakkuk, is a very appropriate idea for the entire Middle East. The net was a symbol of military power, and appears in other figures of Babylonian art where you can see how the gods collected their enemies. Habakkuk wonders if the invasion of Judah by a foreign empire would be the solution to punish the sin of God's people. He also wonders if it would be possible to reconcile the need for punishment with the character of God.

This question should lead us to rediscover the work of Jesus on the Cross and how He was a bridge between us in our sinful state and the perfect God that waits for us.

Gerson Hernández Arizo, teacher, graduated in history. Granada (Spain).

Bibliography

-Carroll, D., in Comentario Bíblico De Oseas a Malaquías. Ed. Mundo Hispano. El Paso, Texas. Vol. 13. Pag. 254-255.

-Garelli, P., (1974). Sumer. El Próximo Oriente asiático. Barcelona: Labor. ISBN 84-335-9310-2.

-Kramer, S.N., La historia empieza en Sumer.1974

-Margueron, Jean-Claude (2002). «La época del Dinástico Arcaico». Los mesopotámicos. Fuenlabrada: Cátedra. ISBN 84-376-1477-5.

-Parrot, A., Sumer. 1964.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o