Remei Oliva tells in a book how she fled to France and ended up in a centre run by Elisabeth Eidenbenz, the daughter of a pastor. “Without her, I would have died”, says the son.

View of the landscape around the Elna Maternity Hospital from Eidenbenz's room / Pilar de nou 999, Wikimedia Commons.

View of the landscape around the Elna Maternity Hospital from Eidenbenz's room / Pilar de nou 999, Wikimedia Commons.

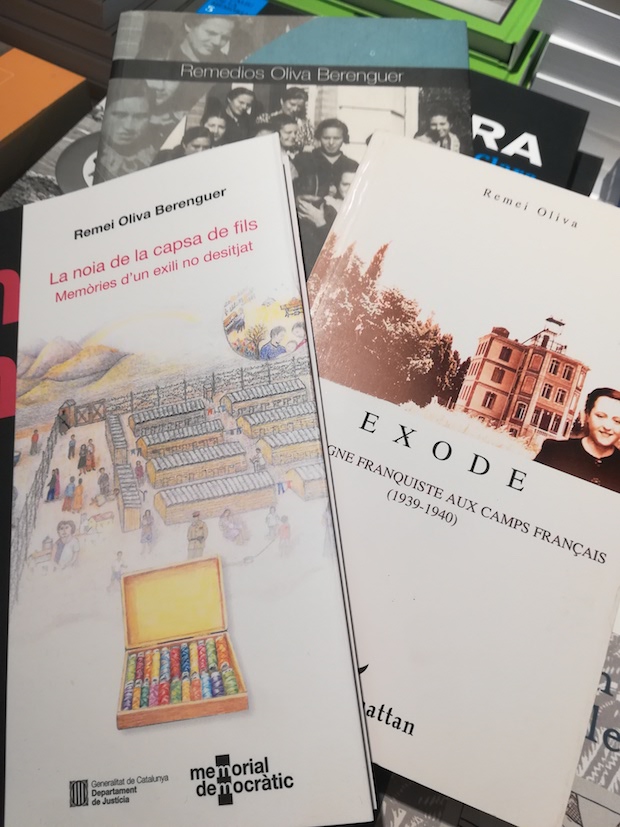

The book La noia de la capsa de fils: memòries d’un exili no desitjat (The girl of the box of threads: Memoirs of an unwanted exile), published by the regional government of Catalonia, recounts the personal testimony of Remei Oliva, during the last days of the Spanish Civil War.

Oliva, now 104 years old, fled to France at the age of 20 as a seamstress, escaping the devastating consequences of the military uprising in Spain.

Once on French soil, along with her parents and her husband Joan, she took refuge first in the Argelès camp, and then in the Saint Cyprien camp.

“The first days after the end of the war, they announced over the loudspeakers that anyone who wanted could return to Spain, but we were afraid of reprisals”, explains Oliva in an excerpt from the book.

At a time when UNHCR is talking about over 100 million displaced people worldwide, Oliva's account recalls the harshness of this situation.

“We had the impression that we were treated like lambs in a flock [...] All those changes without any explanation humiliated us greatly”, says Oliva when she talks about the process in which her relatives were moved back to Algerès and she, pregnant with her first child, was taken to the Maternity Hospital of the neraby municipality of Elne.

This would later become a renowned institution for saving around 800 children and their mothers during the Spanish Civil War and later, the World War II.

Oliva describes Elna as a “majestic” place in appearance, but with an even more remarkable “human touch”.

“If we had left our miserable camp and suddenly found ourselves in a luxurious place, we might have felt uncomfortable, but here it was different. The house was magnificent, but because it had been rented empty, there were only the basics”, she underlines.

A fire to keep warm, a good coffee with daily bread for breakfast or washing facilities were part of the relief that mothers like Remei found in Elne Maternity Hospital at a time of desperation and urgency.

“We were still refugees; our life would be different for a month, but after giving birth we would return to the camp with our child, and then it was even harder”, points out Oliva in the book.

It was at that “improvised maternity hospital”, where, during the course of her journey, she found “a little comfort and, above all, a human warmth that I will never forget”.

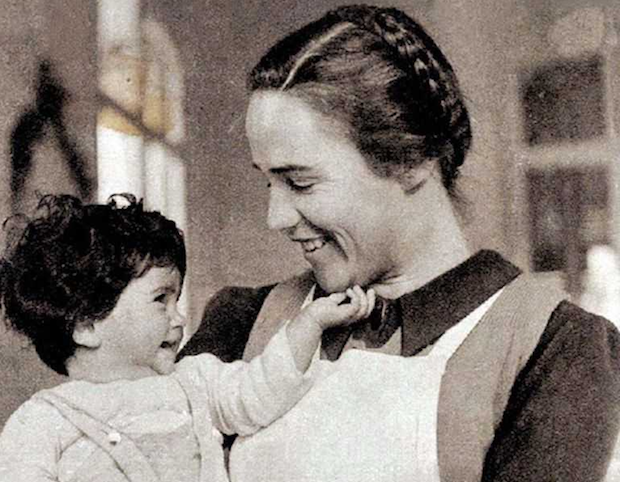

Oliva recalls that “we called Elisabeth Eidenbenz: Miss Isabel”. “She was young and felt pity for everything that was happening in Spain. It wasn't political, she wanted to help. She didn't look at whether [the person] was white, black or Jewish, because she was a Protestant, the daughter of a pastor”, she tells in the video interviews she has done.

In her memoirs, Oliva remembers her with tenderness and as a support in communicating with her husband and parents, who were in Algerès.

Even speaking of her mother, who at that time was ill with pneumonia and had to be transferred to Perpignan, Oliva explains that “I spoke to the director and she offered to go with me to the hospital to visit her. Elne is not far away, but I would not have been able to go alone and without resources, and I was very grateful for her generosity”.

Eidenbenz was one of the key figures in the founding of the Elne Maternity.

The daughter of a Swiss Protestant pastor, she did a unique work at a time when the number of displaced people in Europe was at its highest, until the recent migration crisis.

Eidenbenz died in 2011, aged 97, and her recognition came belatedly. In 2002, she received the Righteous Among the Nations medal, awarded by the state of Israel to people who risked their lives to help Jews during World War II and the Holocaust.

In 2021, the Catalan municipality of Caldes de Montbui dedicated a lookout point to her.

[photo_footer]Remei Oliva today. /Memorial Democràtic, Generalitat de Catalunya [/photo_footer]

Her son Rubèn, born in Elne, takes over Oliva's memory at the end of the book, with some truly moving lines.

“I am the child”, he says. “My mother has written down events far from what should have been 'a normal life', as she used to say; she has done it with simplicity, spontaneity and the authenticity of lived events”.

Reflecting on the different people involved in the development of the story his mother tells, Rubén points outs that he “owes his life to those who acted with such generosity in a time of war and massacre”.

“I am sure that, without Elisabet Eidenbenz, I would have died in the sand of the refugee camp like so many other forgotten babies”, he adds.

History is lived in the small stories and details that even for so long have gone unnoticed.

Those personal testimonies that have been touched by a smile in desperation, by a kind word in the warmth of a fire, by a well-prepared coffee after days on the road, are the ones that “thread” together our common story.

[donate]

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o