God created life in His image and likeness, and granted them the creativity to sculpt and the ability to love.

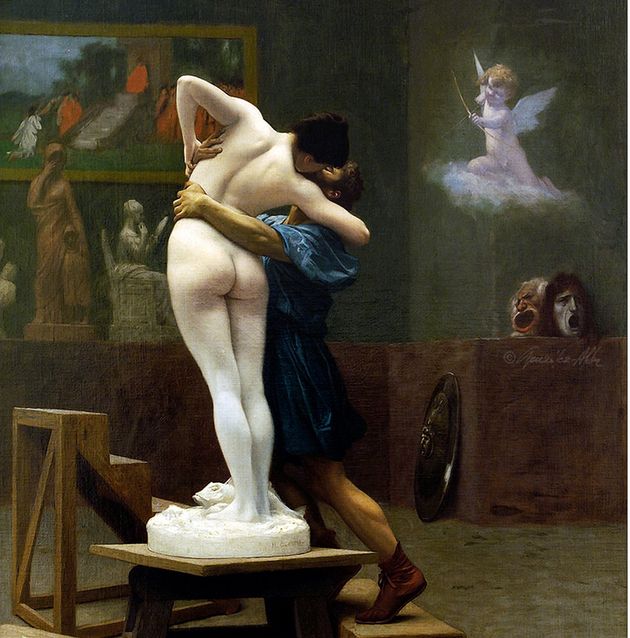

Detail of Pygmalion and Galatea, by Jean-Léon Gérôme. / WikimediaCommons.

Detail of Pygmalion and Galatea, by Jean-Léon Gérôme. / WikimediaCommons.

One of the most celebrated stories of ancient times is the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea.

An inspiration to numerous later works – from The Phantom of the Opera to Pinocchio, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to Shakespeare’s Winter Tales – this tale tells the story of a sculptor who falls in love with his ivory creation.

As Ovid narrates it in his Metamorphoses, Pygmalion fashions the figure of a woman out of snow-white ivory. Entranced by the beauty of his work, he runs his hand over Galatea, uncertain if it he feels skin or ivory.

Then he kisses it, and almost thinks his kisses are returned. The goddess of love, Venus, notices Pygmalion’s unfulfilled passion and grants his wish:

When he returned, he sought out the image of his girl, and leaning over the couch, kissed her. She felt warm: he pressed his lips to her again, and also touched her breast with his hand. The ivory yielded to his touch, and lost its hardness, altering under his fingers…. The lover is stupefied, and joyful, but uncertain, and afraid he is wrong, reaffirms the fulfillment of his wishes, with his hand, again, and again.

This moment of passion was the subject of a moving nineteenth-century painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme. Following the classical dictates of the Académie des Beaux-Arts,the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts of Paris, Gérôme’s painting doesn’t lack dramatic effect.

The three wooden platforms on the floor move our eyes in an upward diagonal line, which are then caught by Galatea’s body until, after Pygmalion’s embrace, she turns unexpectedly to the right, bending to kiss and wrap her arm around Pygmalion, in elegant intensity.

Her ivory legs gain color progressively, as the enlivening effect of their passionate kiss turns her from ivory to human flesh, so Galatea can marry Pygmalion and be his life-long beloved.

In the same year Jean-Jacque Rousseau crafted his The Social Contract, he wrote also his own rendering of the story of Pygmalion and Galatea.

One of the first melodramas in the history of theatre, Rousseau’s play is also a secularized version of Ovid’s myth, for now it is Pygmalion’s own love, instead of the intervention of Venus, which infuses Galatea with life.

She awakens as Pygmalion strikes his chisel for the last time, touches herself, and says, “me.” As her eyes gain vision and are inundated with colors, she touches another statue and says, “not me.” Then she turns to Pygmalion and says, “Me again.”

In a story with curious parallels, Genesis narrates that when God saw that Adam was alone, he sculpted a woman – the first woman – for him.

Then he breathed life into Eve, and Adam erupts in passionate poetry, and calls her “bones from my bones and flesh from my flesh,” probably feeling her skin as Pygmalion felt Galatea’s.

Modern translations cannot capture all of Adam’s lyric Hebrew poetry: previously he was naming animals, and now he calls Eve in the Hebrew isha, woman, for she came out of man, ish.

The biblical account of creation involves also a sculptor, the animation of inanimate matter, and a romantic encounter; the difference is that now God is the artist. He sculpts and he breathes life.

Adam was looking at the animals, and saying, “not me.” He looks at Eve, and says, “me again”.

And, seeing the thrill of mutual encounter, of identification and transformation, of feeling one another’s body, of being energized by passion, I imagine God must have sighed from a distance, observing this scene of love, and said, “me again” too.

He created life in his image and likeness, and granted them the creativity to sculpt and the ability to love. Humanity would flourish, would create masterpieces and fall in love at each generation, following the flow of that first breath of life.

And I guess God sighs still, when he sees us in workshops or on park benches, in moments of work or of passion. He cherishes our joys, and repeats it also when he sees us saying, “me again”.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o