If that body was really gone, if Jesus had come back to life, then the matrix of reality is altered; tragedy is not the final result of goodness.

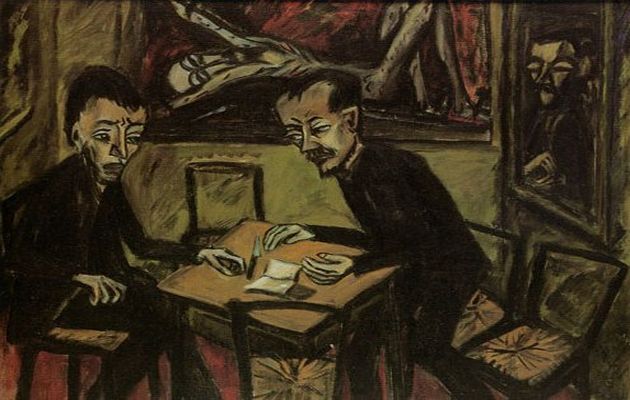

Two men at the table, by Erich Heckel.

Two men at the table, by Erich Heckel.

Is goodness feasible in an evil world?

Can we maintain innocence as we seek to enter and influence the tough dynamics of the marketplace, politics and society? Can we sustain love and generosity for people who disdain and even abuse us?

Or, to put it in biblical language, is it possible to follow Christ through a path that does not lead to a cross? For anyone who has really attempted it, the practicalities of goodness are no small challenge.

A painting got me thinking about these things – actually, a painting based on a novel. Erich Heckel’s Two Men at the Table uses spectral colors and pointed lines to convey a tortured scene of anguish and tension.

We see two men around a table in a claustrophobic little room; a piece of paper and a knife between them; a portrait which seems to haunt the encounter; and a crude picture of Jesus on the cross, surrounded by a bloodied atmosphere.

The older man leans forward, apparently challenging or menacing the younger man, who does not know what to do, oppressed by faces and colors alike.

Heckel drew inspiration for this scene from Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, and subtitled the painting, “To Dostoyevsky.”

In this novel, the Russian writer crafts the story of Prince Myshkin, a “completely beautiful human being,” as Dostoyevsky described in a letter: a generous, kind, loving, forgiving, innocent young man, who enters St. Petersburg’s corrupt society and seeks to love people, only to be dismissed and manipulated in return.

Myshkin is like a figure of Christ in an un-Christian world, and he disputes the love of a beautiful woman with brutal Rogozhin, who attempts to kill Myshkin and who has at home a portrait of Christ taken down from the cross as a dead body without life, without hint of a possible resurrection.

Beautiful Nastassya oscilates between the innocent goodness of Myshkin and the harsh character of Rogozhin, until she decides for the worse man, who kills her in the end.

Heckel’s painting seems to portray this last encounter between the two men at Rogozhin’s house, where they spent a tense night veiling over Nastassya’s dead body.

Dostoyevsky’s experiment to place a good man in an evil world highlights Myshkin’s tragic fate. People don’t know what to do with him; his purity is misunderstood and abused.

A scholar described that Myshkin is a “more riddling and more tragic figure of lost absolutes. In a world where God is simply dead flesh, a good man becomes simply an idiot.”[1]

We may question at several points how much Myshkin resembles Jesus’ actual example, and notice that he lacks the fiber and force of the Jesus he represents, for instance.

But Myshkin reminds us still of the upper hand of evil which seemed to hover over Jesus’ last hours: Jesus facing false accusations silently, beaten and spit at, at the hands of traitors and hypocrites who take his life at the end, and who mock his final prayer, “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.”[2]

Yet, even as we sense the upper hand of evil seemingly everywhere, and wonder if we can emulate Jesus’ graceful endurance of mistreatment, we can also remember that the painting hanging on Rogozhin’s wall is not the end of the story.

Jesus was lowered from the cross crumbled and broken, and the friends who had not fled could only weep that Friday afternoon. But Sunday was still to come, with news that would change everything: that broken body, and all the tragic human fate it sums up and represents, was gone.

We may believe it or be wondering about it still, but the news of resurrection carried by the beams and airs of dawn electrified people with a cosmic kind of possibility: if that body was really gone, if Jesus had come back to life, then the matrix of reality is altered; tragedy is not the final result of goodness, nor is realism synonymous with pessimism.

Evil may appear to have the upper hand, and goodness may lead to a painful cross, but there is life beyond pain, and hope beyond tragedy, and the model of one whose victory over evil changes the outcomes for us all.

[1] A. S. Byatt, Prince of Fools, at The Guardian

[2] Luke 23:34

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o