Never-before-showcased clay tablets documenting the first diaspora go on display at Jerusalem’s Bible Lands Museum.

Bible Lands Museum Jerusalem

Bible Lands Museum Jerusalem

We know they sat on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates, and that they wept. But a new exhibit at Jerusalem’s Bible Lands Museum puts faces and names to the Judean exiles in ancient Babylonia 2,500 years ago.

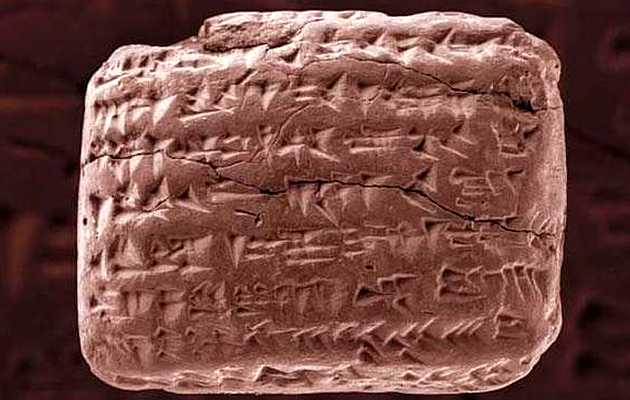

“By the Rivers of Babylon” showcases a collection of about 100 rare clay tablets from 6th century Mesopotamia that detail the lives of exiled Judeans living in the heartland of the Babylonian Empire. Through these mundane Akkadian legal documents written in cuneiform, scholars have breathed life back into generations of Judeans who lived in Babylon but whose names and traditions speak of a longing for Zion.

The Al-Yahudu tablets are part of a private collection that has never before gone on public display. Their provenance is unknown; they likely turned up somewhere in southern Iraq, but no one knows when. After decades on the antiquities market they ended up in the hands of a private collector, David Sofer, who offered to loan them to the Bible Lands Museum. After two years of labor, the exhibit is opening to the public on Sunday.

“It puts a face on the real people who went through these fateful events,” Dr. Filip Vukosavovi?, curator of the exhibit, told The Times of Israel. The tablets preserve a wealth of Judean names — including the familiar Natanyahu — of the exilic community, and even include a handful of Aramaic inscriptions

The exhibit takes visitors through the final days of Jerusalem before its destruction by Nebuchadnezzar in 586 BCE, and transports them to Mesopotamia, where the deportees were resettled. At the center of the gallery is a model of a Mesopotamian village, animated to show light shimmering on the canals at night and farmers plowing the field at midday, similar to those in which Judeans made their home.

Before the Al-Yahudu texts were found and studied, scholars only had an outline of life for Judeans in Babylon, said Dr. Wayne Horowitz, Hebrew University’s professor of Assyriology, who helped prepare the exhibition and the corresponding academic literature.

“We had before this an outline, a tradition, but as historians we couldn’t prove it. And now we’re actually seeing the community living its life, really fleshed out.”

He compared the experience of the exiled Judeans to that of new immigrants to Israel in the early years of the state. They were settled in a region of southern Babylon that had been ravaged by years of war and forced to rebuilt infrastructure and dig canals — the rivers by which they wept when they remembered Zion.

“Once they had built the infrastructure they were allowed to settle and build their lives,” Horowitz explained. Within a short while, the community became more prosperous and secure, a fact documented in the financial documents preserved in clay.

“It’s impossible to exaggerate when it comes to the importance and the amount” of information gleaned from the tablets, Vukosavovi? said. He called the Babylonian exile the “most important event in the history of the Jewish people.”

Each document catalogs when and where it was written and by whom, providing scholars with an unprecedented view into the day-to-day life of Judean exiles in Babylonia, as well as a geography of where the refugees were resettled. The earliest in the collection, from 572 BCE, mentions the town of Al-Yahudu — “Jerusalem” — a village of transplants from Judea.

“Finally through these tablets we get to meet these people, we get to know their names, where they lived and when they lived, what they did,” Vukosavovi? said.

The texts help dispel the misconception that the Judeans in Babylon were second-class citizens of the empire, living in ghettos and pressed into hard labor. While some toiled in base drudgery, others thrived, owned property, plantations and slaves, and became part of the Babylonian bureaucratic hierarchy.

“It teaches us that we weren’t slaves, like we were slaves to the Pharaoh,” Vukosavovi? said. “It teaches us that we were simply free people in Babylon, living not only in Al-Yahudu, but also in a dozen other cities where Jews either lived or did their business.”

Employing a variety of media — animated videos, antiquities from the destruction of Jerusalem, illuminated manuscripts, and illustrations to complement conventional text — the gallery culminates with the clay tablets accompanied by iPad tablets replete with information to better understand the cuneiform texts.

“One of the challenges of creating this show was to make it accessible [to the general public],” museum director Amanda Weiss said. “We had to create a way that would entice all ages to relate to this information.”

“This is an amazing collection. It is truly the world premiere of this archive on display,” said Weiss. “It’s never been published, it’s never been displayed until now.”

She said the museum admits thousands of schoolchildren each year, and she hopes that the exhibition will “supplement or inspire learning” of biblical history, “to take it away from the boring or the difficult.”

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o