My greatest struggle is not my neighbor, coworker or family member. My greatest struggle isn’t even Satan. My greatest struggle is myself.

Photo: Adam Ool (Flickr)

Photo: Adam Ool (Flickr)

Chuck Colson tells the story of visiting a Baptist church in Florida when the pastor made a confession from the pulpit.

“The pastor stood up to preach on the parable of the Good Samaritan and said, ‘Let me start with an illustration. Do you remember last year when the Browns came forward to join the church?’ Everyone nodded.

The Browns were an attractive, middle-class family, friendly, outgoing, influential in the community. Sure, everyone knew the Browns.

Suddenly the pastor switched gears. ‘Well, the same morning a young man came forward,’ he said. ‘He gave his life to Christ that day.’

Surprised murmurs rippled through the sanctuary. No one remembered the young man. The pastor picked up his story. ‘Well, after that day we worked with the Browns, got them involved in the church, signed them onto committees.’

‘But the young man …,’ the pastor paused. ‘Well, we could tell he needed help. We gave him counseling, but then lost track of him.’

‘That is, until yesterday.’ Here the pastor held up a newspaper. ‘As I was preparing my message, I picked up this paper. And here was a photo of the young man. He was charged with killing an elderly woman.’

A hush fell over the congregation as the pastor continued: ‘I never followed up on that young man. And now I realize that I am the priest in the story of the Good Samaritan – the man who saw someone in trouble and crossed to the other side of the road.’

‘I am a hypocrite.’”

Colson comments, “In the silence that followed, we realized we were all guilty. We had acted exactly the way God warns against in the second chapter of James: We had welcomed the rich man and snubbed the poor man.”[1]

Just like this pastor, we all fail. At times we fail miserably. We don’t do what we wish we had done. We do what we wish we hadn’t done (Rom.7:15-20). We struggle with desires we wish we didn’t have. We struggle with ourselves.

The Bible’s Moral Law as a Mirror

When we look at what the Bible teaches, the high standard of holiness and love that the Lord calls us to, we should be overwhelmed by our own sin. Take for example Paul’s teaching in I Corinthians 13 about love. This is the most powerful statement on love in the entire history of mankind. Do you live out the full reality of love all the time? Are you always patient, kind and not easily angered? I’m not. Do you always forgive and persevere? I don’t. Do you feel convicted when you read and meditate on I Corinthians 13? I certainly do. God’s character reflected in the Bible’s moral law is a mirror to help us see ourselves.

This experience of conviction is simply being honest (a biblical word for humility) about who we are.

We are not who we should be. This is one of the crucial truths of the gospel. Luther and Calvin, and more importantly Paul, teach us that we only know ourselves as we know God. As we come to know the holy and loving God, and the moral law that reflects his character, we become more aware of how often, and how deeply, we fail to live as we ought. As Paul writes, “Through the law, we become conscious of sin” (Rom. 3:20).

Without this foundational truth, the atoning death of Jesus makes no sense. Without understanding the character of God, and thus comprehending how far we fall short of God’s holiness and love, we don’t need a savior or a gospel. But when we are faced with our sin, we realize our need for a savior; we repent and are born again.

But what then? We are forgiven, but we are still sinners. Unless one advocates the unbiblical idea of total sanctification, we still fail, both willfully and by omission. How do we deal with our sin after we have come to faith? Are we honest about how we struggle?

We each know our own weaknesses and sin, don’t we? You know yours. I know mine. We know how often we fall short in loving our families. We know our own lustful desires, the binges of self-pity and the surges of anger in which we indulge. When we see the truth clearly, it is like a mirror reflecting back the flaws and blemishes in our lives and character. We often feel like the pastor who stood in front of his congregation and said, “I’m a hypocrite.”

My Greatest Struggle is Myself

A friend described to me her stay as a missionary in Africa. As she was describing both the joys and sorrows of her experience, she suddenly stopped and looked stunned as she said, "You know, I took all my problems with me right into the jungle." Her greatest problems weren't others or even the trials of being a cross-cultural missionary; her greatest problems were in her very self. The character weaknesses and struggles she faced in her home country traveled with her to Africa.

Photo: Mike Belgard (Flickr)

Photo: Mike Belgard (Flickr)My greatest struggle as I have lived my life has been myself. I expect that it will remain so. I don't believe that this is pessimistic in the slightest, as I will try to explain.

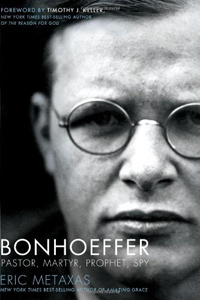

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German pastor, became world-renowned for his writings and his courageous stand against Hitler and the Nazis. While in prison, and before he was killed by the Nazis, he wrote a very honest poem:

Who am I? They often tell me

I stepped from my cell’s confinement

Calmly, cheerfully, firmly,

Like a squire from his country-house.

Who am I? They often tell me

I used to speak to my warders

Freely and friendly and clearly,

As though it were mine to command.

Who am I? They also tell me

I bore the days of misfortune

Equally, smilingly, proudly,

Like one accustomed to win.

Am I then really all that which other men tell of?

Or am I only what I myself know of myself?

Restless and longing and sick, like a bird in a cage,

Struggling for breath, as though hands were compressing my throat,

Yearning for colors, for flowers, for the voices of birds,

Thirsting for words of kindness, for neighborliness,

Tossing in expectation of great events,

Powerlessly trembling for friends at an infinite distance,

Weary and empty at praying, at thinking, at making,

Faint, and ready to say farewell to it all?

Who am I? This or the other?

Am I one person today and tomorrow another?

Am I both at once? A hypocrite before others,

And before myself a contemptibly woebegone weakling?

Or is something within me still like a beaten army,

Fleeing in disorder from victory already achieved?

Who am I? They mock me, these lonely questions of mine.

Whoever I am, Thou knowest, O God, I am Thine![2]

We see in Bonhoeffer’s poem someone who knows that the outward image of who he is does not completely match up with the inward reality. We see someone who is struggling between what he knows he should do and be and the tumultuous emotions he is experiencing as he waits to be murdered by the Nazis. We see someone who feels like a weakling and a hypocrite.

We see in Bonhoeffer’s experience the greatest struggle we all face. We feel broken. We feel weak. We feel like hypocrites.

One writer explained that many psychologists have observed this struggle: "It is not the outward storms and stresses of life that defeat and disrupt personality, but its inner conflicts and miseries."[3] This statement describes an internal pressure cooker of pain— a struggle with what we've done and what we haven't done; a struggle with who we are.

There are many sources of this pain. It comes from our failures, inconsistencies and hypocrisy. There is often a gap between our ideals and our behavior, between our expectations and our performance. As a result, we often produce an image of ourselves in order to impress others or to gain their approval. Yet, in this deception there is an inconsistency between the outward mask and the inward reality. This inconsistency leaves a gap in personhood, a void in being. One individual who went in for counseling described this reality: "I have the frightening feeling that deep inside me, no one is there."

The contemporary crisis in “identity” and “self-esteem” is really a crisis in self. Individuals feel broken because they are broken. But instead of admitting this reality, they complicate the problem by trying to deny it.

The Blindness of Narcissism

Photo: VisitSanAntonio (Flickr)

Photo: VisitSanAntonio (Flickr)We’ve all seen the movies where someone is in a room of mirrors, and yet they don’t know where they are. They see endless reflections of themselves, but ultimately they are lost in a maze. This is a picture of narcissism. Narcissism includes a lack of self awareness, a blindness to who one truly is. Self-absorption leads people to be self-deceived. Without healthy relationships that can reflect back one’s weaknesses and strengths and personality quirks, someone doesn’t see themselves accurately.

The blindness of narcissism adopts the spirit of the age; it indiscriminately welcomes the self and the self-orientation that our culture promotes. We are told that we need to love ourselves and to affirm ourselves – and we believe it. From this perspective, one's desires, feelings and choices are viewed as inherently good and proper.

But there is still an internal cognitive dissonance. We know that we don’t always live the ethical principles that we profess. We realize that we are selfish and are guilty of not living as we ought. Sometimes individuals can hide from a conscious awareness of this ethical failure. But even these individuals feel broken and incomplete and have a sense of guilt. They react to their brokenness by building up an area of gift or ability. This pride is a puffed-up response to insecurity. Thus, the basic root of the blindness of narcissism lies in pride. However, there is another equally devastating trap that the believer can fall into.

The Tar Pit of Despair

Many of the best-preserved dinosaur bones are found in old tar pits. Dinosaurs came to a water source to drink and were caught in the sticky tar. And the more they struggled to escape, the more they were engulfed in the tar. For many people, life can feel like a tar pit. The more they struggle, the more they fail. The tar pit is a place of depression and hopelessness.

Photo: Lorne Thomas (Flickr)

Photo: Lorne Thomas (Flickr)The tar pit of despair is the equal and opposite error to the blindness of narcissism. The tar pit of despair, as the name communicates, is as negative in its view of self as blindness of narcissism is positive. People who fall into the tar pit of despair see or feel their own brokenness and are self-consciously insecure. Their problem is with their very selves – they don’t like what they see when they look in the mirror.

On the foundational level, both forms of brokenness (the blindness of narcissism’s self-conscious pride and the tar pit of despair’s self-conscious insecurity) are symptoms of a larger problem— sin. The reason human beings feel broken is because they are broken. The reason people feel selfish is because they are selfish. We all are.

In responding to the individual brokenness we feel, there usually is a movement in one of these two directions. We move toward pride or toward self-conscious insecurity. As the titles suggest, blindness of narcissism and the tar pit of despair describe opposite responses to self-understanding.

Until individuals come to understand that they need forgiveness for their selfishness and healing for their brokenness, they are condemned to wallow in the tar pit of despair or continue the treadmill of the blindness of narcissism that endlessly searches for something that will make them feel better about themselves.

But biblical Christians also often struggle at exactly this point. They understand the need for forgiveness for their sin (justification by faith), but don’t understand how to grow in faith (sanctification). How do we become who we want to be and what the Bible teaches that we can grow toward? Part of what scripture gives us is a clear reflection of who we are.

There are three categories of a biblical worldview that are very helpful as we begin to think about this issue: creation, fall and redemption

Creation

How does God understand us?

We are made in God’s image (Gen. 1:26-7), and God sees us as inherently valuable. As human beings made in the image of God, we have the ability to choose, have relationships, create and work.

Think of Adam before the fall. God gave him the work of naming the animals (Gen. 2:19-20). He had the creativity of choice and responsibility. Before the fall, it was not good that he would be alone (Gen. 2:18). The importance of relationships is fundamental to what it means to be human. All of these dimensions are part of how God has created us in his image.

Rembrandt self-portrait. Photo: David Adams (Flickr)

Rembrandt self-portrait. Photo: David Adams (Flickr)When God made each one of us, he made a masterpiece. Imagine a gorgeous painting by Rembrandt that leaves its viewer with a sense of awe and wonder. From a biblical point of view, each human being was made to be just that— a masterpiece of beauty and splendor.

But we don’t feel like masterpieces, do we?

Why?

The Fall

The story line of the Bible is our story line as well. What happened after creation? The fall was not merely Adam and Eve’s problem; it is our problem. Our ancestors rebelled, and we now live in a fallen world. As Paul says in Romans,“For creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God” (Rom. 8:19). We have a broken relationship with God; we have broken relationships with other people; we are also broken in who we are – we are not who we want to be. We have multiple, conflicting desires.

Imagine the Rembrandt painting that I described above hanging in a beautiful museum. Then imagine an insane man coming in and slashing the painting with a razor knife. The horror of this desecration and senseless destruction is terrible.

What would we do in response? We would immediately seek to save the painting by initiating a process of restoration and bringing in a master craftsman who could lovingly repair this priceless treasure.

What does God do in response to our damage and brokenness? The same thing. God has initiated a restoration plan.

Redemption: God’s Mission to Rescue Us

Paul explains that “God demonstrates his own love toward us in this: while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). God, seeing our value and loving us, initiates a rescue mission in order to forgive and heal us.

The entire story line of the Bible is a record of how God has initiated a rescue mission to save us from our sin. But we are still inclined to sin; we are still sinners.

This sin causes a lack of peace with one's self, a feeling of disintegration. I would like to state very clearly that every person I have ever known has struggled intensely with these feelings and this experience. Every person is broken. And believers are no exception—they struggle with pride and insecurity just like everyone else.

How do we move from forgiveness to growth? How can we experience healing and hope? How do we become who the Lord wants us to be? The first step is to better understand who we are and how God made us, and this is the topic of next week's article.

[1] Chuck Colson. “Are you Impressed? Hypocrites and Good Samaritans Church Book Series, #4.” August 4, 1999. BreakPoint Commentaries. http://www.breakpoint.org/bpcommentaries/entry/13/10057

[2] Dietrich Bonhoeffer. “Who Am I?”Christianity and Crisis. (March 4, 1946). .

[3] J.B. Phillips. Your God is Too Small: A Guide for Believers and Skeptics Alike. (New York: Touchstone, 2004), 34.

Greg Pritchard earned his MA from Trinity School of Divinity before continuing on to finish his PhD at Northwestern University. The intersection of theology, history, philosophy and sociology is Greg’s primary focus both in teaching and writing. He has taught graduate-level courses on apologetics, theology, history, leadership, the New Testament, ethics, and Christian Thought at American, European, and Asian institutions of higher learning. His book, Willow Creek Seeker Services, has been published in four languages. In addition, Greg has worked as the COO at a Chicago investment firm. Currently, he serves as the President of the Forum of Christian Leaders and as the Director of the European Leadership Forum.

The Forum of Christian Leaders (FOCL) is the sponsor of the European Leadership Forum (ELF), which seeks to unite, mentor, and resource European evangelical leaders to renew the biblical church and re-evangelise Europe. This happens first at the ELF's annual meeting that occurs each May in Poland. In addition to the ELF, FOCL is host to an online media library and learning community for evangelical Christians. Learn more at foclonline.org and euroleadership.org; or join us on Twitter @FOCLonline and Facebook Forum of Christian Leaders.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o