Mursilis was unsure if the storm god was indeed the reason for the plague that happened between 1350-1325 BCE. He panicked because libations and offerings were about to cease.

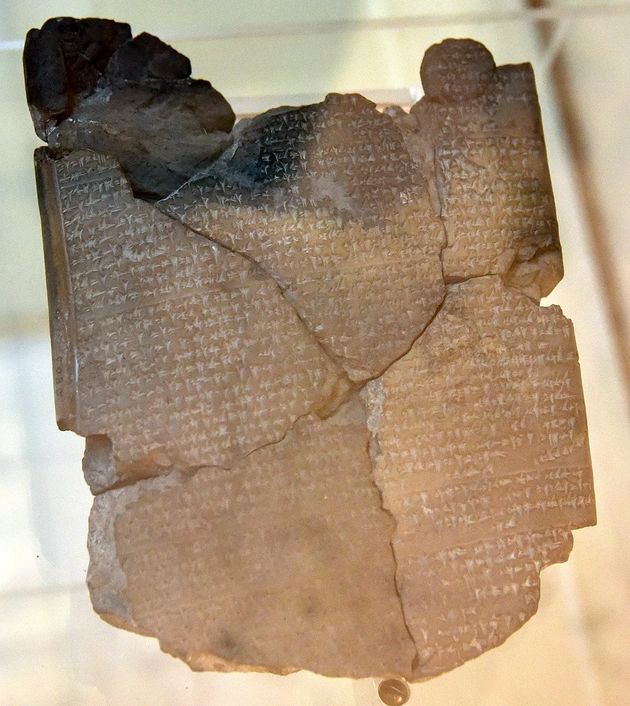

Plague Tablet of Mursilis II, Istanbul Archaeology Museum. / Osama Shukir

Plague Tablet of Mursilis II, Istanbul Archaeology Museum. / Osama Shukir

Among the many tablets discovered in Hattusa, the capital city of the Hittite empire now located in Turkey, the plague tablet of Mursilis II is worthy to be highlighted.

This tablet contains prayers to the Hittite gods for deliverance from a plague which had been ravaging the Hittite countryside for more than 20 years since the reign of Mursilis’ Father, Suppiluliumas II.

The plague in question happened sometime between 1350-1325 BCE and it resulted in many deaths, including the death of Mursilis’ brother Arunawanda.

The prayer begins with bewilderment as to the possible reason to the plague. Mursilis states “When I celebrated festivals, I worshipped all the gods, I never preferred one temple to another!” He then goes on to say that he asked for a sign or omen but the gods remained silent.

The situation got so bad that even the priests who were offering sacrificial loaves and libations began to die. It was at this point in time that through an oracle he learned of two lost tablets.

The first tablet dealt with offerings to the river Mala, which had been ignored since the day of his father. The second dealt with an oath that had been made in conjunction with the Hattian storm god Telipinu.

Apparently, a long time ago the Haitians of Kurustama had entered a conflict with the Egyptians. The conflict had been settled under an oath given to the storm god. It turns out that Mursilis’ father Suppiluliuma had not honored this oath by attacking the Egyptian territory of Amka; and when he brought back prisoners a plague spread (possibly from the prisoners themselves) and caused the land of Hatti to be infested.

Mursilis continues his prayer by humbling himself and crying out for mercy. He claims he has not sinned but understands that the sin of his father should fall upon him. He confesses his father’s sins and the sin of the nation.

In a poetic petition, he points out that a bird takes refuge in its nest, and the nest then saves its life. Similarly, if a servant repents and appeals to his lord, the lord will not punish him.

Despite all this, Mursilis is still quite unsure if the storm god is indeed the reason for the plague. He panics because libations and offerings are about to cease and cries out to the gods to send him a prophet, a sign or a dream.

The surrounding kingdoms have begun to attack Hatti. He pleads that the sun-goddess Arinna, a protective deity of the Hittites, should not bring her name into disrepute and that the gods should banish the “evil plague to [those other] countries”.

BIBLICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Hittites had various forms of prayer. In the arkuwar, the petitioner may confess his blame or displace responsibility as though he is being accused by a deity for a crime.

Presumably the god will then make a judgment. In the prayer called mugawar the petitioner calls on the mercy of God to abandon his hostility. It seems that Mursilis’ prayer uses both of these devices.

One of the defining characteristics in Mursilis’ prayer is also the principle of divine retribution. Man has sinned against the gods and deserves punishment. The nature of this sin however varies. It may be that the correct offerings weren’t made or that an oath wasn’t honored and therefore a specific god was insulted or offended.

The plague and punishment was then viewed as the retribution of the offended god. In a polytheistic culture, figuring out which god was offended was quite an ordeal. Kings often needed guidance from oracles and seers, but even then there was no guarantee that what they were doing was correct. Mursilis’ fear, insecurity and panic is quite palpable throughout the text.

In the Biblical worldview one observes that sin is explained in different terms. Sin is explained as a covenant breach or covenant unfaithfulness.

Hosea 6:6-7 explains: “For I desire mercy, not sacrifice, and acknowledgment of God rather than burnt offerings. As at Adam, they have broken the covenant; they were unfaithful to me there”.

Adam’s sin was one of rebellion and disobedience, he saw that the fruit could make him “as god” and he chose to eat it and become his own god. This act of hubris brought disaster not only to himself but all of creation.

Are plagues God’s punishment? Are they the result of humanity’s mismanagement of earth and the result of playing to be ‘god’? For the Biblical writers the answer to these questions are not necessarily mutually exclusive!

We should sway away from an image of a vindictive God. Vindictiveness is what we see in humans and in pagan deities, like the Hittite gods when their particular desires are not fulfilled. This is not the God of the Bible.

The God of the Bible is just. He doesn’t change. He sets covenants, and boundaries but humans may violate these in their responses, and different responses may have different consequences.

Mursilis’ prayer also bears some resemblance to the story of David’s plague found in 2.Samuel 24 and 1.Chronicles 21. Although one must say that it completely lacks the redemptive arch found in the Biblical story.

In the story David calls for a census, however we know from previous Biblical narratives that this was a prerogative that belonged to God and not David (Num 1:1-2). David in essence choses to play god.

God castigates David for his hubris with a 3 day plague over Israel. David intercedes on behalf of the people. The plague stops at the threshing floor of Araunah (also named Ornan) the Hittite. God commands David to redeem and buy the threshing floor, build an altar, and offer burnt offerings.

Following the offerings the threshing floor is consecrated and the plague ceases. We learn later, that it is in this very spot where Solomon’s temple, the dwelling place of Yahweh will be built.

Here we have a beautiful typology. We all have played to be god at one point or another. Our hubris is the cause of calamity in the world. We deserve judgement but God in his abounding grace and mercy does not act vindictively.

He sets boundaries to the plague. The plague ends in the place where God has chosen for his habitation. In the same way God chooses the church, Christ redeems it and through his sacrifice consecrates and protects it from the judgement that is to come to the world.

As the Apostle Paul eloquently puts it in 1.Cor. 15:22, “For as in Adam all die, so in Christ all will be made alive!”

Marc Madrigal is a Board member in the Istanbul Protestant Church Foundation in Turkey.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Bill T, Arnold; Bryan E. Beyer. Readings form the Ancient Near East. Baker Academic, 2002. p. 202-204.

- Winfred P. Lehmann and Jonathan Slocum. Hittite. University of Texas at Austin Linguistics Research Center. March 18, 2020.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o