The last novel by Javier Marias Asi empieza lo malo (“This is where it all goes wrong”) is about the fear of our lives being destroyed by those secrets which could cause earthquakes at a moment’s notice.

Javier Marias´ last novel reveals the secrets of a miserable marriage before the Spanish Divorce Law.

Javier Marias´ last novel reveals the secrets of a miserable marriage before the Spanish Divorce Law.

Looks can be deceiving. We sometimes think that we know someone until they suddenly reveal a double life that we would never have imagined. We all have secrets, things that we keep hidden. One day, they will be brought to light, but in the meantime they are kept covered up by a blanket of untruths and pretence. The last novel by Javier Marias Así empieza lo malo, asks whether it is better to live a lie, rather than face up to humans’ incapacity to forgive.

There are certain authors with whom a special relationship grows up. We no longer read their books because of their literary worth, but due to an emotional bond which prevents us from analysing their work at its true value, but which give us access to a world which is as personal as one’s own memories. This is what happens to me with the so-called “eighties generation” in Spain, including writers like Javier Marias, Antonio Muñoz Molina, and Javier Cercas, whose last titles take us back to Spain during the “Transition” period.

Back then, I would see Javier in the bus that I took in the afternoons to the Faculty of Philology of the Complutense University in Madrid, where he taught theory of translation, having returned from Venice to live with his father, the philosopher Julian Marías. I was doing a Dutch class in the afternoons, after trying to fit German into my Journalism studies. As neither of us had learnt how to drive – following a family tradition, as I suppose that our parents didn’t drive either –, we would catch a bus that left from near where we both lived.

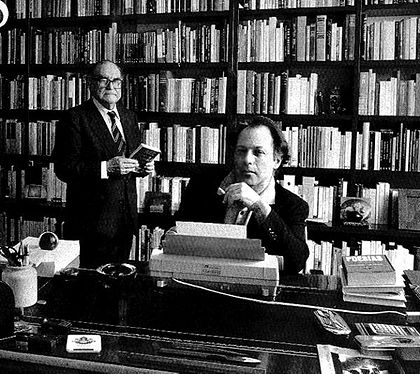

Javier and Julián in the apartment they shared in the eighties.

Javier and Julián in the apartment they shared in the eighties.It is impossible to conceive of the narrator in this story without recalling “the young Marías”, as Juan Benet called him when Javier started to write at the age of 17. The relationship between the main character (Juan De Vere) and a film director and his wife (Eduardo Muriel and Beatriz Noguera), are reminiscent of the anglophile engineer who changed Spanish literature in the twentieth century – Benet, according to Marías –, and the time that he spent in Paris with his uncle Jess – his mother’s brother, who made porn and horror films, together with his partner Lina Romay–. This is a novel of initiation, what the Germans call “bildungsroman”, a story of education and learning in life.

THE EIGHTIES

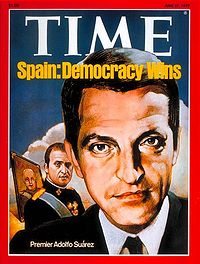

The Spanish Transition was organized by former Franco supporters, who became democrats.

The Spanish Transition was organized by former Franco supporters, who became democrats.At the beginning of the eighties, Spain was still in the period of transition to democracy. People buried their memories of the civil war and a series of changes began which would bring about laws on issues such as divorce – promoted by the Union of the Democratic Centre party of Fernández Ordóñez–. The history of this unfortunate couple is incomprehensible without understanding that before that people would get married forever. The story is moreover told by Javier Marías, who is a bachelor but whose parents were very close – although his mother died young–.

The Transition was a time of “coat turning”, where dyed-in-the-wool Franquists presented themselves as democrats. This was so much so that some, who had gone so far as to report others for not being sufficiently supportive of the regime, congratulated themselves at the end of the dictatorship and assumed liberal ideas – as in the case of Camilo José Cela–. Javier’s father was accused of right-wing tendencies, even though Franco had put him in prison on false accusations which branded him as a republican. That is why, when Javier declined the National Novel Prize in 2012 for “The Infatuations” he said that, “if my father didn’t deserve the National Prize, neither do I”.

This is the reason why the paediatrician Van Vechten hides his dreadful conduct during the Franco regime, pretending that he helped the victims of the dictatorship. The rapid conversion of various biographies not only manages to cover up the past, under an imposed silence, but also invents supposed anti-regime heroic acts. Accordingly, in El Impostor (The Impostor), Javier Cercas asks how Enric Marco not only claimed to have been a survivor of a Nazi concentration camp, but also managed to become the secretary general of an anarchist trade union at the end of the seventies, owing to his imagined activities against the dictatorship. The whole country seemed to have accepted this imposture.

DO WE “LIE MORE THAN WE TALK”?

Javier Cerca shows Spain´s imposture during the Transition, as a reflection of our full of lies life.

Javier Cerca shows Spain´s imposture during the Transition, as a reflection of our full of lies life.If the Transition was based on concealment and lies, it is because our lives feed on self-deceit based on lies that have so often been repeated that we start to believe that they are the truth. What an author like Cercas discovers is that “fiction saves, while reality condemns”. It is as if “we needed fiction in order to continue living”; “everyone here has invented an anti-Franco past”, like Marco’s “to be able to stand themselves”, since “he is, in a way, what we all are”.

Stories like El impostor and Así empieza lo malo, speak of “our insatiable and humiliating need to be loved, accepted, admired”, says Cercas. “We all play some kind of role”, since we “are all narrators of our own lives”. As a literal translation of a Spanish saying goes, “we lie more than we talk” and we offer others an image that is not always true. The problem is that, at “in the end, the truth will out”.

When Muñoz Molina tries to understand the murderer of Martin Luther King, he returns to Lisbon of the eighties, where the criminal at the centre of his novel Como la sombra que se va (Waning shadows) stayed, and where he also lived when he wrote his book Invierno en Lisboa (Winter in Lisboa). What he discovers is his own guilt, his lies to his wife and the distance he feels towards his new-born son, seeking to escape from a reality which appears anodyne, the weight of family responsibility, which make him wish for a different life.

WHO ARE WE TRYING TO FOOL?

Molina thus identifies himself with King himself, with his clandestine lover, Georgia Davis, who follows him from city to city and is also with him on his last night at the Lorraine Motel. This is something that, as Christians, we prefer not to hear, because the honesty of these books, contradicts the pretensions we hold of being better than others and free of infidelity. We believe that our spiritual language can hide who we really are, while the Word of Truth reveals our imposture.

Muñoz Molina identifies with King´s muederer, coming back from his experience in Lisbon in the eighties.

Muñoz Molina identifies with King´s muederer, coming back from his experience in Lisbon in the eighties.

God’s law is like a mirror (James 1:23), which shows us who we are. The temptation is to look away and pretend that we are not as bad as others, but in the eyes of God, we have all been found wanting (Romans 3:20). We can’t pull the wool over his eyes. He knows what we do, think and say…

The wretched couple in Marías’ novel, hides a past that can’t be erased, even though it has not yet been made public. As in life itself, everything starts with an interest which immediately entraps you, leading to a reiterative monotony, but as in Cercas’ work, the ending is full of surprises.

Just when the story has become predictable, full of empty dialogues and trivial questions, the truth appears. This is a truth that is held ransom to spurious interests, hidden for legitimate reasons of self-protection, and hushed up out of prudence against the consequences of revealing it, and the resentment unleashed at not having known it earlier...

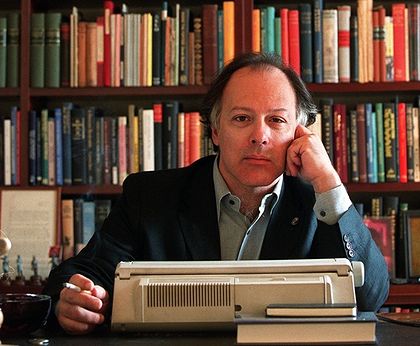

Marías is known for his technology loathing, he does not drive, or use the mobile, and he still writes with the typewriter.

Marías is known for his technology loathing, he does not drive, or use the mobile, and he still writes with the typewriter.HE WHO SEES EVERYTHING

Jesus says that “there is nothing hidden that will not be disclosed, and nothing concealed that will not be known or brought out into the open.” (Luke 8:17). This is a novel about truth and lies, secrets and their revelation, the dilemma between knowing them and revealing them, or knowing them and hiding them. It is about the fear of our lives being destroyed by those secrets which could cause earthquakes at a moment’s notice

Are we who we say we are? Why do we do the things we do? “God will bring every deed into judgment, including every hidden thing, whether it is good or evil (Ecclesiastes 12:14). He knows what is in our hearts (1 Samuel 16:17) and he hears our words (Matthew 12:36). He hears and sees everything. We are not alone with our secrets.

“There are many things in my life that I do not want to put under the gaze of Christ – says R.C. Sproul– Yet I know there is nothing hidden from Him. He knows me better than my wife knows me. And yet He loves me. This is the most amazing thing of all about God’s grace. It would be one thing for Him to love us if we could fool Him into thinking that we were better than we actually are. But He knows better. He knows all there is to know about us, including those things that could destroy our reputation. He is minutely and accurately aware of every skeleton in every closet. And He loves us.”

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o