Christianity departs from any kind of moralism. What is good news for Duch, is bad news for those who consider themselves too be good and righteous.

No one believes that they are capable of doing such things, but History teaches us that anyone, in the right circumstances, is capable of the same level of evil.

No one believes that they are capable of doing such things, but History teaches us that anyone, in the right circumstances, is capable of the same level of evil.

Forty years later, the leaders of the Khmer Rouge have for the first time been condemned for the part they played in the Cambodian genocide of 1975–1979.

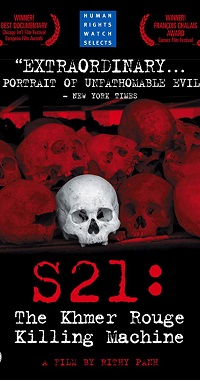

Pol Pot killed almost two million people – more than a quarter of the country’s population. He led a paranoid regime that saw enemies everywhere. The slightest whiff of dissent was enough to be incarcerated in Security Prison 21 (S-21), an old school converted into an extermination camp. The documentary “S-21: The Khmer Rouge Death Machine” talks about what happened in this prison through the accounts of the gaolers and survivors, who speak openly about this hellhole. It is a chilling but necessary testimony of Man’s capacity for evil.

The documentary S-21 refers to one of the prisons of the system.

The documentary S-21 refers to one of the prisons of the system.Before the war, Cambodia was an independent and neutral country, with a population of 7.7 million inhabitants. However, in 1970, Prince Sihanouk was ousted by a military coup. Cambodia became mixed up in the Vietnam War, suffering heavy US bombing and becoming embroiled in its own civil war, in which 600,000 people died. When the Khmer Rouge emerged victorious in 1975, many people were moved to the countryside under forced collectivization; the schools were shut, the currency abolished and religion prohibited. In came the work camps, surveillance, famine, terror and executions.

In those four years of terror, the Khmer Rouge destroyed the life of so many people that in Cambodia it is nowadays hard to find anyone whose family or friends were not victimized, tortured, imprisoned, raped or murdered. It was a period of terrible brutality that is seldom talked about, when compared to the other genocides of the twentieth century. What’s more, this all happened relatively recently.

ABSOLUTE TERROR

Rithy Pahn’s documentary opens our eyes to this terror. Prison S-21 was a human mincer, a foul hole, where people were overcrowded, imprisoned in infrahuman conditions, in a nightmare of privations and abuse. It is estimated that at least 14,000 people were imprisoned and murdered within its walls. Its interrogations were simply a way of getting people to denounce others and thus feed reports that endorsed the parody of Angkar’s revolutionary justice. The cruelty of the torturers knew no bounds. They promised their prisoners freedom, only to end up destroying them (not simply killing them as one of their victims says), treating them like animals, long before killing them with a blow to the head.

Pol Pot establishes a paranoid system that sees enemies everywhere.

Pol Pot establishes a paranoid system that sees enemies everywhere.This chronicle of total desolation opens up wounds that are still bleeding in a country that has remained in a state of devastation since the Vietnam War. The documentary sits both torturers and victims in front of the cameras, trying to make them engage in an impossible dialogue. Their conversations have a strange rhythm to them, violent in their silences, atonal and inexpressive. The aging torturers – who during the regime were only between 14 and 22 years old and were indoctrinated to kill savagely – explain with unperturbed expressions how they treated men, women and children, depersonalized as “enemies” and no longer considered as human beings.

Their account reaches the diabolic extreme of staging their actions at the exact location of the events (now housing the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum), in a theatre of unrepeatable cruelty. We get a glimpse of the horror suffered by those inmates, through their words and gestures in empty spaces, surrounded by reports and old black and white photographs of those who disappeared. We see how in those old cells – now eerily empty – the gaolers yelled, beat, hurled abuse and became the personification of their victims’ death. It is as if there were a strange naturally-activated mechanism in them that removed their supposed humanity, turning them into killing machines, not hesitating for one second or stopping to question themselves.

THE DANGER OF LOOKING OVER THE EDGE

If such a reality seems impossible to us it is because we are still ignorant of the real face of evil. When we see it painted like this, it seems so abominable and unbearable, that we wish we had never seen it. This story gives us a glimpse of what would appear to be the end of humanity. François Bizot, a scholar of Buddhism at the Sorbonne University in Paris and a former prisoner of the Khmer Rouge, recounts his experience in his book The Gate. He asks himself how it is possible that his gaoler was not a psychopath but a normal man, which makes it all the more awful.

Forty years later, two leaders of the regime have been condemned in the courts.

Forty years later, two leaders of the regime have been condemned in the courts.“The heart is deceitful above all things”, says the prophet Jeremiah. It is “beyond all cure. Who can understand it?” (17:9). No one believes that they are capable of doing such things, but History teaches us that anyone, in the right circumstances, is capable of the same level of evil. Many people believe that they have a heart of gold, but it’s frightening to realize what one is capable of in certain situations. It is dangerous to look over the edge... The capacity for cruelty – even for the most peaceful-minded individuals –, is unimaginable, as these events show. These mild people suddenly gave way to an outbreak of violence without precedent.

Where does this evil come from? “It would be wonderful if Hitler and his paranoid cabinet had been aliens”, observes the Spanish writer Javier Cercas, “because we would be saved”. But “it is not possible. The disease wasn’t in Germany but in the soul”. European enlightened society has been telling us for centuries that Man is naturally good, but it is still incapable of explaining the mystery of evil.

A NEW DUCH?

Until now no one had been condemned for this genocide, which killed two million people some forty years ago. The main torturer of the Khmer Rouge, Kaing Guek Eav, is known by the nickname Duch. He was the person in charge of the S-21 prison. At the age of 76, Duch now admits that he is guilty of the crimes for which he is accused: war crimes, torture and homicide. After having heard the evidence given by some of his victims, he asked through tears to be given the “most severe punishment possible”, which, in his case, was life imprisonment.

Duch, the main torturer of the Khmer Rouge, converted from Budhism to Christianity through a Cambodian evangelical pastor.

Duch, the main torturer of the Khmer Rouge, converted from Budhism to Christianity through a Cambodian evangelical pastor.After the fall of the Khmer Rouge, Duch escaped to China, where he worked as a language teacher. When he returned to Cambodia, he taught mathematics under a different identity. Journalists of the Far Eastern Economic Review found him in 1999, after twenty years anonymity. He was working as a medical assistant in a US refugee camp in the North of Cambodia. In the report published at that time, he already recognized his participation in torture and murders. Now he has admitted to it publicly, with tears in his eyes, before the International Court that is handling his case, following the evidence given by a woman who lost her husband and four sons at the Choeung Ek concentration camp, just outside the capital.

After his wife was murdered by a group of bandits in 1995, it is reported that Duch converted from Buddhism to evangelical Christianity through a Cambodian pastor who had lived in the United States but was working as a missionary in Battambang for the Golden Christian West Church. His doesn’t appear to be an isolated case. According to The Observer, two thousand Khmer Rouge had accepted Jesus as their saviour by 2004.

WHEN “SORRY” JUST ISN’T ENOUGH

Christian conversion is based seeking forgiveness and faith, but “what is there to forgive, if the person isn’t guilty of anything”, says one of the survivors in the documentary. The logic behind this is indisputable: “We are told to forget it; that it’s the past, but how are we to forgive them if they don’t recognize their guilt”.

The Khmer Rouge killed almost 2 million people, a quarter of the whole population.

The Khmer Rouge killed almost 2 million people, a quarter of the whole population.There is much more to seeking forgiveness than saying “sorry”. Talking about forgiveness in historical memory, without facing up to the mistakes of the past, is to dodge reality. You can’t experience the joy of forgiveness before feeling the weight of guilt. Christian hope teaches us to be amazed by God’s grace when we stop making excuses for ourselves and face up to the evil in us, as Duch does.

It isn’t a cheap form of grace. It is immensely precious: The cross of Jesus Christ! How can the righteous judge declare the unjust to be just? That is the Apostle Paul’s question when he writes to the Romans: Does God justify evil? This idea makes us indignant, but that is the scandal of the gospel. Through the justice and the punishment meted out to another, God “justifies the ungodly, their faith is credited as righteousness” (4:5).

For those who justify themselves, this is intolerable, but for those who recognize the evil within them, there is no better news than this: If God provides salvation in Christ, we are saved by and through him, in spite of the things that we have done. This is where Christianity departs from any kind of moralism. What is good news for Duch, is bad news for those who consider themselves to be good and righteous. Those of us who recognize the darkness in our hearts, hold on to that cross and are amazed by the wonder of His grace.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o