With such division in our political leadership, is there any wonder that the tensions over Brexit remain so high?

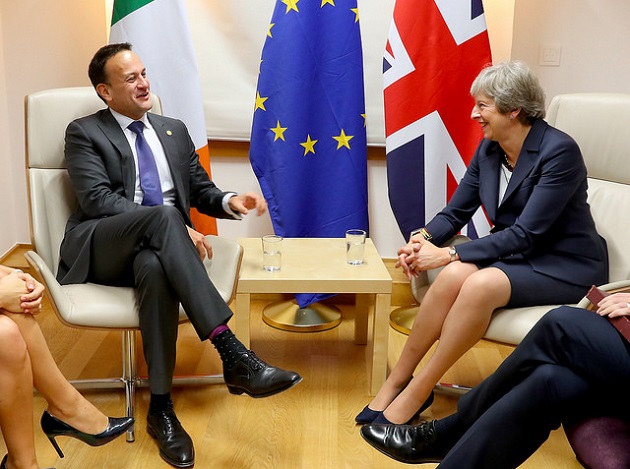

Prime Minister Theresa May visited Belgium to attend the EU Council. During her visit she held a bilateral meeting with Leo Eric Varadkar, Taoiseach of Ireland. / Number 10 (Flickr, CC)

Prime Minister Theresa May visited Belgium to attend the EU Council. During her visit she held a bilateral meeting with Leo Eric Varadkar, Taoiseach of Ireland. / Number 10 (Flickr, CC)

Theresa May came back from Brussels last week having failed to reach any breakthrough on the vexed issue of the Irish border backstop (how to ensure there will be no return to a hard border in the event that the UK and EU fail to agree a new trade deal within the transition period after Brexit next March).

Waiting for her return were members of her own party who had been arguing over how much say Parliament should have over the final deal on the terms of withdrawal. Some Conservative MPs had also reacted sharply to the PM’s suggestion to extend the transition period to allow more time to negotiate a trade deal that would prevent a hard Irish border.

One wonders which group Mrs May finds it easier to negotiate with: the leaders of the EU27 nations, or the factions within her own party. The problem is that a clear mandate is needed to negotiate well, and because she failed to secure that in the snap general election last year, the PM has a wafer thin majority in parliament. It’s a titanic struggle to get consensus in her cabinet, let alone in her party. With such division in our political leadership, is there any wonder that the tensions over Brexit remain so high?

The President of Lithuania hit the nail on the head on Wednesday when she said, ‘We do not know what [the UK government] want, they do not know themselves what they really want – that’s the problem.’ The EU Referendum was supposed to bring resolution to divided opinions about the value of EU membership – primarily in the Conservative Party – but since then the country has become more and more deeply divided over the issue.

The verse in the Bible that comes to mind is, ‘No house divided against itself can stand’ (Mark 3:25). This has been quoted many times in politics, one notable case being Abraham Lincoln in 1858. Before becoming US president, he declared that the government could not endure, divided as it was over slavery. He said the Union would cease in the end to be divided – but not by breaking up; it would have to become either all one thing or all the other. Tragically it took a four year civil war and the death of three-quarters of a million people to resolve the issue of slavery and keep the Union together.

Slavery had come to permeate every other political question in America in the late 1850s, and in a similar way, Brexit is the one overriding issue in Britain today. Of course, in most ways there is no comparison between these two situations, yet I can’t help but wonder whether the greater issue today is not Brexit per se, but, as it was in Lincoln’s time, our ability to remain united as a country. I’m not thinking primarily about the nations of the United Kingdom, but across our society more generally, the ability to hammer out differences and reach a consensus over the way forward.

The first-past-the-post system of British elections makes for adversarial politics; we accept the ‘winner-takes-all’ principle because there is always a time limit on any regrettable decision: the longest we have to put up with a government we dislike is 5 years. But with Brexit it’s different. For a generation immersed in the ethic of consumerism (if you don’t like something you’ve bought you can always take it back), it can be a struggle to accept the permanence of leaving the European Union. There is no easy going back – not without losing our hard fought exceptions and currency – which is why those marching on Saturday called for a second Referendum while there is still time, before the axe falls on 29th March next year.

Although I voted firmly to Remain, I believe that it’s quite possible for Britain to be a successful nation – in the long term – either in or out of the EU. The ‘prize’ of Brexit is the long term independence and sovereignty of the UK parliament, but no-one should fool us into thinking that extricating Britain from four decades of integrating our economy and institutions into the European Union is possible without a costly period of adjustment over a number of years.

But will that prize still be there if, through the fraught process of leaving the EU, the political fabric of our society becomes unravelled? Our ability to debate differences civilly, respect others with opposing views, accept a government we didn’t vote for, protest lawfully, uphold civil society and ultimately seek the common good are crucial to the freedom and prosperity of this country – and these values were formed over centuries of Christian influence.

The fight for EU membership will soon be over, but the struggle for British democracy is what matters more.

Jonathan Tame, Director of the Jubilee Centre (Cambridge, UK).

This article first appeared on the Jubilee Centre website and was republished with permission.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o