No event can ultimately be tragic because, thanks to God’s undeserved grace, every experience in our life is ultimately for the good.

The film by Monzón takes us back to the days in Spain when certain districts were ruled by delinquents who saw all outsiders as the enemy.

The film by Monzón takes us back to the days in Spain when certain districts were ruled by delinquents who saw all outsiders as the enemy.

“We are so accustomed to disguise ourselves to others that, in the end, we become disguised to ourselves.” It is with this quotation of François de la Rochefoucauld that Javier Cercas start his novel Las Leyes de la Frontera (The border laws), which has now been turned into a film by Daniel Monzón.

I was very impressed by the novel. There are times when books that are “like a mirror, you do not read them, rather they read you”.

When I read the first reviews of the novel, it did not appeal to me particularly. I have always liked Cercas’ novels – not so much his articles, which get a bit lost down the political rabbit hole of the day – but his new book seemed to be another journalistic reconnoitre of the transition to democracy in Spain (1975–1982).

I thought that it was going to be too much like his previous book about the attempted coup d’état of 1981 (Anatomía de un instante). I was wrong.

Las leyes de la frontera is probably one of the most personal novels yet written by Javier Cercas. When I borrowed it from the library to give it a chance – I recommend doing this when one has misgivings about a book – I was hooked from the first page.

Returning to this Spain of the end of the 1970s brought back memories not only of my own generation – Cercas was born in 1962 and I in 1964 – but the book also spoke to fears of a present in which boundaries are more diluted than ever.

This is a book about the confusion of adolescence, a time when people try to set themselves apart from their family and get away from the monotony of life. It is the time of first loves, of awakening to sexuality, but especially of the loss of an innocence that we will never retrieve.

The book provides an alternative narrative of the official story of Spain’s transition to democracy, which forgets the trials and tribulations to concentrate only on an anaesthetized and mythologized version. It makes us face up to the dark side of its uncertainties and false truths.

Although Cercas is originally from the west of Spain – he was born in the town of Ibanhernando, in the province of Cáceres –, he moved to the Catalan city of Gerona at the age of 15, like the main character in his story. Franco had been dead for three years, but the country continued to be governed by his laws and nothing had changed.

Many Spanish cities then had what was called a barrio chino, literally a “Chinese district”, not because it was home to Asians but because it was where the marginals in society wound up, creating hotspots for crime and prostitution.

An elegant part of Girona today – full of fashionable restaurants and shops – the barrio chino was a “damp, desolate and dirty” area, in the heart of a city still reeling after the Spanish Civil War.

Cercas remembers it as “a dark and religious village, hemmed in on all sides by the countryside and covered in mist in the winter”. At that time, the city was surrounded by a belt of districts inhabited by immigrants who had arrived in Catalonia from all over Spain: “people who didn’t have a place to call their own and had made their way here to try to make a life for themselves”.

One of these districts was home to the famous young delinquent Juan Moreno Cuenca (1961–2003) – known as “El Vaquilla”. His lawyer, who knows Cercas, wrote a book about his life.

Cercas read it at around the same time as he visited an exhibition – held both in Madrid and Barcelona – about the “Quinquis of the 1980s”. A Quinqui – with parallels to “tinker” in English, a name taken from the Spanish word quincallero for scrap-metal dealer – is considered by Spanish gypsies as someone who is halfway between a gypsy and a payo (non-gypsy), but the word is used more generally just to refer to delinquents.

The expression was popularized by Eleuterio Sánchez, alias El Lute, a Spanish writer who began life literally a scrap-metal dealer before taking up theft as a living and becoming a famous Franco-era outlaw.

“For the first time in my life – Cercas says – I was at an exhibition that talked about me, about my own experience”. The exhibition contained pinball machines, film posters (this underworld spawned a whole cinema genre to which some Spanish directors like José Antonio del la Loma and Eloy de la Iglesia dedicated themselves full time, while others, like Carlos Saura – Deprisa, Deprisa – just dabbled in it) and boxes of albums by Los Chichos and Los Chungitos (two Spanish bands popular during the Movida Madrileña counter-cultural movement that took the Spanish capital by force in the 1980s).

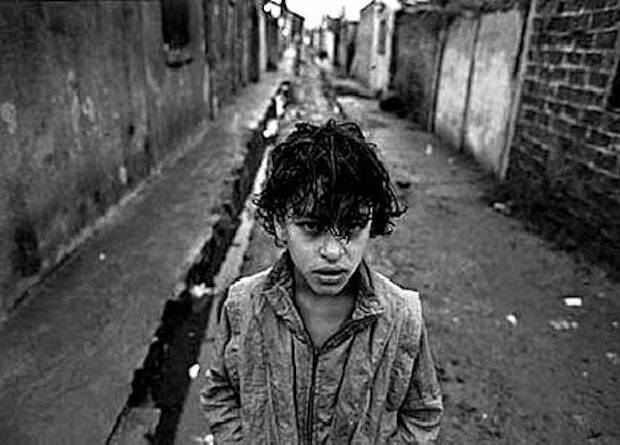

At the end of the exhibition a room displayed large black and white portraits of boys who grew up at that time. They were all dead. Cercas asked himself: “How come I am not one of them?”.

That is the origin of his story, whose main character is not a quinqui, but a middle-class adolescent like Cercas. Ignacio Cañas, the protagonist, meets El Zarco – a character based on the infamous El Vaquilla – in the summer of 1978 when he is 16 and he is immediately given the alias “Gafitas” (four-eyes).

What gets a boy from a good family mixed in petty crime and drug addiction? Our parents taught us about the importance of steering away from bad company.

[photo_footer]Cercas says that his character did not take drugs to fit in but because he liked it. [/photo_footer]

In her book The Nurture Assumption (1998), the psychologist Judith Rich Harris, reinforces this message when she says that friendship groups have a greater influence on children’s upbringing than their parents.

The process of generational assimilation means that we seek to adopt the fashion, hair styles and ideas of our friends. From an early age, we want to be like others. What varies is the understanding or frustration of the parents witnessing the changes that follow.

What is interesting about the film is that the main character is a loner who is bullied at school. Children can be cruel, but for Gafitas, “the main feeling of adolescence is fear”.

At school someone starts making fun of him. They call him “Dumbo”. They laugh at his awkwardness with girls and his boffin glasses. Soon words are not enough. They start hitting him and he tries to retaliate in jest. But soon any laughter turns to tears and the desire to escape.

“Going to school every day became an ordeal”, Cañas recalls. “For months, I went to bed crying and I woke up crying. I was angry, resentful and felt totally humiliated. I felt trapped. I wanted to die”.

He takes refuge at home, where he spends his time reading and watching television. He loves the Japanese series The Water Margin, which the Spanish national television broadcast at the end of the 1970s – a kind of oriental version of Robin Hood. That is where the title of the book and the final conclusion of the story comes from.

What happens in the summer of 1978 is that, however low or intimidated one may be feeling, a sixteen-year-old can’t stay at home all day. Cañas visits pool clubs – the kind of places that were later turned into gaming arcades in the 1980s.

The clubs had table footballs and pinball machines that teenagers could play on. That is where Cañas meets El Zarco and Tere. Until then he had always been a good boy but that moment marks the start of his walk on the wild side.

There was a pool club like that opposite the evangelical school that I attended at the end of the 1970s. The school then had a lot of boarders who came from problematic families.

Some of the children were particularly violent. I don’t have many good memories from those years. I only felt happy on the days that I didn’t have to go to school. Like Gafitas (Cañas), all I did was read and watch television – that is, until the confusing years of adolescence arrived.

The only way of surviving those years was, like Gafitas, by finding a protector. I had a good friend who was tougher than me. He loved football – which I never have – but he didn’t have many friends. He lived with his single mother in a working-class neighbourhood of Madrid.

I remember going to his house once. The feeling of fear in the street was palpable. The quinquis were everywhere, death-staring all outsiders.

After I finished middle school, I was sent to high school in the centre of Madrid. I have found newspaper articles from the time describing the “unsustainable situation of altercations and violence” that reigned at the San Mateo School.

I remember policemen running up the stairs; students launching benches and plant pots out of the window; far-right groups brandishing sticks at the gate, beating up anyone with long hair.

[photo_footer]Until he met El Zarco and Tere in a gaming arcade, Gafitas was a good boy.[/photo_footer]

It is no wonder that the school was closed down and remained closed until 2011 when it was reopened as a high-school for advanced students. I used to spend my days there on the benches of the park across the street, getting used to the smell of the weed that my classmates smoked.

This was at the time of the arrival to power of the socialist government in Spain and of the start of the Movida Madrileña. This was also during the term as mayor of Madrid of the Professor Tierno Galvan, who famously encouraged the spectators of a rock concert to “get high”. Wild times.

As the exhibition showed, the myths that grew up around delinquents like El Vaquilla were not invented by people, but rather by the media, by songs and films.

In 1980 the Spanish singer Joaquin Sabina sang a song to José Joaquín Sánchez Frutos, alias El Jaro, a year after that delinquent’s death at the age of 16, shot in the act of carrying out a robbery.

Around the same time the director Eloy de la Iglesia was making Navajeros, a film about the same person starring José Luis Manzano. At the end of that decade, both actor and director were addicted to heroin and soon after a stint in prison in the early 1990s, Manzano appeared dead from an overdose at the director’s home.

In Cerca’s novel, the character of the director Fernando Bermúdez is a mixture of De la Iglesia and another Spanish director, José Antonio de la Loma, who made a film about El Vaquilla.

One of those films gave Cercas the inspiration for the character of Gafitas – a timid middle-class adolescent who wises up when he enters El Zarco’s gang, prepared almost to betray the leader in a struggle for power and for his girl. Gafitas acts as bait – with his studious priest-school look and his Catalan – for the gang’s heists.

They break into cars and target old ladies with handbags. In the end, he is the only one to get away.

And fiction fed real life: El Jaro admitted that he had been schooled by the film Perros callejeros (1977) by José Antonio de la Loma. The actor playing El Vaquilla in that film, Ángel Fernández Franco (1960–91), became the real-life criminal El Torete.

He made three more films with De la Loma, together with his brother, who died in 1995. In the fourth, he played El Vaquilla’s lawyer – like Cañas’ character in Leyes de la Frontera – shortly before dying from AIDS.

The main character is one of the few survivors. Raúl García Losada left cinema after playing El Vaquilla. Now he is an evangelical preacher at a church in a working-class neighbourhood in Madrid.

Faced with the sociological and psychological determinism blamed for these lives of crime, Cercas is amazed by the mystery of life : “From the end of the 1970s until the end of the 1980s Spain had spawned hundreds of uprooted youngsters like El Zarco, and the large majority of them had died of heroin addiction, AIDS, violence or were simply locked up in prison. But that wasn’t me.

The same could have happened to me, but it didn’t. I had done well. I wasn’t in prison. I hadn’t tried heroin. I hadn’t got AIDS. I had never even been arrested”.

[photo_footer]It is galling to think that most of the boys of that lost generation are now dead.[/photo_footer]

“Adolescents – as Cercas says – find no greater satisfaction than in being able to put all the blame for their troubles on someone else”. Cañas blames his parents, when he starts to get home in the early hours of the morning after a night out on the town.

“For any young boy of that age, until he gets locked up himself, prison is more or less equivalent to death: something that happens to other people”.

He took “chocolate” and pills, but not heroin or cocaine. “I didn’t take drugs to be accepted; but because I liked them” says Gafitas. “You could say that I began taking them out of some kind of obligation and it ended up being a pleasure, or a vice”.

Cercas builds his novel around a writer’s interviews with the characters in this story. This creates ambiguity and a sense of unease, reflecting the imperfections of life.

I’m part of the baby boomer generation which experienced the youth unemployment of the 1980s – we had gone through schools that were too small for us and even the military service couldn’t absorb our great number.

In this context, drugs reaped havoc and HIV had people dropping like flies, from one day to the next, without knowing what had hit them. The question that Gafitas – now a lawyer – asks himself is the key to this story: why them and not me?

Gafitas, who has become a Cañas the lawyer, comes across El Zarco again at the eve of the new millennium. “He was no longer the same. He had had time to create and destroy his own myth. At the beginning of the 1970s, he was in some ways a precursor, but at the end of the 1990s he had almost become an anacronym”– all in the space of 20 years.

“A shipwreck from another time. It was all in the past: the country had changed completely. The dark years of juvenile delinquency were seen as the death rattle of economic depression, repression and the lack of freedom under Franco. After twenty years of democracy, the dictatorship seemed long gone and we all lived in an inebriated state of never-ending optimism and prosperity”.

Ignacio Cañas (Gafitas) works at the best law firm in town. Now in his fifties, his parents have died but he feels like “now everyone wants to be forever young”.

Married and divorced, “when I had got the money and the position that I had spent years working for, I was overwhelmed with a feeling of uselessness; the feeling that I had done everything that I was destined to do, and that all that was left for me were the dregs of life, an insipid extra time, or perhaps the feeling that the life that I led was a mistake, a borrowed life, as if at some point I had taken the wrong turn or it had all been some big misunderstanding”.

Antonio Gamillo, alias El Zarco, has spent more than 25 years in prison or on the run. Put on trial fourteen times, he is accused on nearly six-hundred counts.

He has been wounded on six occasions in clashes with the police and another ten times in street or prison fights. On two occasions he has been tried for homicide, but has been absolved in both.

He has been through seven juvenile detention centres and sixteen prisons. He has managed to escape from all the detention centres and from many of the prisons.

He has organized various riots and has started two hunger strikes. And yet the Director General of Penitentiary Services believes in his rehabilitation. “A daily mass-going catholic, he is full of good intentions and believes in the natural goodness of man. In short, a dangerous individual.”

El Zarco has become proud and petulant. Cañas is shocked by his arrogance and his contemptuous impatience, but he is also described with the fatuity of a person who has known success too early in life. His arrogance covers up his fragility.

The lawyer orchestrates and operation to get him out of prison under the subterfuge of his marriage, playing on the heartstrings of the media to move public opinion and get from Catalonian conservative nationalism what they haven’t yet achieved from the leftist centralists in Madrid.

The problem is that El Zarco’s fiancée takes control of the story to snatch the limelight in the sensationalist press – a mediapath just like her supposed husband to be.

[photo_footer]This film shows how life has a dark side to it that we cannot understand. [/photo_footer]

Las leyes de la frontera is, above all, a love story. It is out of his love for Tere that, in the summer of 1978, Gafitas becomes part of El Zarco’s band. He happens to abandon his life of delinquency at just the right time, not knowing what happens to the other member of the band and always wondering what relationship

Tere had with El Zarco. He believes that El Zarco saved his life but he is afraid that, now in prison, he will betray him. When they are thrown together again, a secret relationship develops with Tere; they listen to old music as he tries to understand the past.

When Tere disappears again, he suspects that they have been using her to get back at him. The meeting reveals many misunderstandings, but also leaves us with a lot of questions.

The Bible reveals to us a God that cares about us. The small details and the direction of our life do not escape his control. He delivers us from many evils, but he also allows us to experience seemingly senseless tragedy and death.

Some events in our life seem providential, even though he also oversees those that we don’t even notice (Matthew 10:29 –31). When the people in the Bible look back, they discover apparently trivial events in their life that contributed to accomplishing the plan that God had prepared for them. God guides them, even when they are not aware of it.

Life has an inscrutable dark side. God weaves pain, loss and distress with pleasure and joy as he works out his will in us. When Paul says that “in all things God works for the good” (Romans 8:28), he is referring to the unsurpassable power and wisdom of God. He is capable of getting things done in spite of our weakness.

Christians know that God loves and cares for them, even in the midst of adversity. We do not get everything we want, but we trust in Him who knows not only our desires, but is also aware of our needs.

The theologian Paul Helm, former professor at King’s College London, said that “The Bible does not, it seems, promise that a person’s life will form a discernible pattern with a beginning, a middle, and an end. … It would be completely false to Scripture to suppose that in order for people to be assured that the events of their lives are ordered by providence for a good end, they should be able to discern some overall pattern or ‘story’ in their lives. The pressing need to discern such a pattern can often lead to unnecessary frustration and heartache”.

According to Scripture all experiences in life have value or “are for the good”. The problem is that until all the events in a person’s life have taken place, any kind of pattern will necessarily be retrospective.

In that sense, in his study on Providence, Helm concludes that the meaning of a life stands outside that life. As Job says, “Though he slay me, yet will I hope in him” (13:15).

What then happens when a life seems to lack meaning, marked by monotony, loss or adversity? No event can ultimately be tragic, because thanks to God’s undeserved grace every experience in our life is ultimately for the good.

Luck is just a word to pinpoint our ignorance. Whoever has Christ, has everything they need in life.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o