We feel pressured to live and work as a salvation project where I’m the hero of my own story.

Some time ago, on my way to studies in Oxford, I landed at Gatwick Airport.

The usually distracted routine–have my passport controlled, get my bag, go through customs–was startled by these images.

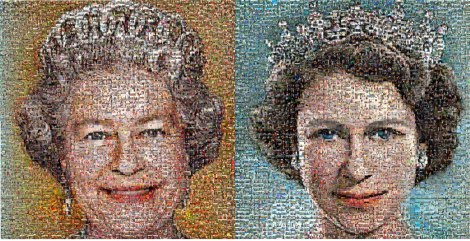

The twin mosaics, called The People’s Monarch, celebrate Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee. As I glimpsed them from afar, something felt odd. The colors and shapes seemed out of balance. As I approached the huge images, however, I realized that what had disturbed me was actually what rendered that work of art fascinating: it was composed by thousands of pictures of everyday people.

There were babies laughing, a girl and a rabbit, groups of friends at the beach. One image in particular, an elderly couple holding a red rose, caught my attention. It looked like a charged moment, like they were celebrating a special occasion. Their eyes brimmed with meaning.

Those sights somehow lingered in my mind. They looked like a fitting metaphor for a world where each of us lives our own little stories yet wonder what larger plot are we part of. If we could take some steps back and marvel at where our stories fit the larger narratives of our families, communities, nations, and humankind, what larger shape would emerge? Where would our single moments fit?

It is a crucial question for the way we live, as philosopher Alisdair MacIntyre points out in his classic After Virtue:

I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’ We enter human society, that is, with one or more imputed characters— roles into which we have been drafted—and we have to learn what they are in order to be able to understand how others respond to us and how our responses to them are apt to be construed. … Deprive children of stories and you leave them unscripted, anxious stutterers in their actions as in their words. Hence there is no way to give us an understanding of any society, including our own, except through the stock of stories which constitute its initial dramatic resources.

Today we are often exhorted to be unique, be special, write our own lives, don’t let anyone tell us who we should be. You be you, girl. But while there is a lot of value in individualism, it can become an anxious pursuit where the full weight of human meaning rests on our individual shoulders.

We feel pressured to live and work as a salvation project where I’m the hero of my own story and where, in a world deprived of greater meaning, my failures are pointless and my successes fleeting. We work desperately to prove our worth and justify our existence, a way of life responsible for much of our modern ills: stress, depression, overwork, fractured families, loneliness.

But to be aware of a larger plot – to see ourselves as characters whose failures count for something and whose successes have greater purpose – changes things. Even dark moments can compose a beautiful picture. Even the perfect day at the beach acquires new company.

The question, of course, is what story do we find ourselves in? Why are we here? What’s our purpose? If you’re willing to explore the mosaic some more, here’s a good place to start. Make that two.

And I’ll wonder some more about the meaning of the rose for that couple too.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o