Experts on spirituality and youth in Spain stress the need for a more concise analysis to understand current Generation Z trends.

![Photo: [link]Nicolas Lobos[/link], Unsplash CC0.](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/68fb7755d6296_Maryou.jpg) Photo: [link]Nicolas Lobos[/link], Unsplash CC0.

Photo: [link]Nicolas Lobos[/link], Unsplash CC0.

Several international media outlets have recently reported on a change in people's beliefs.

“The march of secularism has stopped”, reported The Economist last July, emphasising the return to faith among young people.

Even platforms such as Teen Vogue talk about how younger generations are “redefining and rethinking religion". But to what extent are such concepts stil valid?

One of the leading voices on this issue is Óscar Salguero Montaño, who holds a doctorate in Social and Cultural Anthropology with honours and specialises in the study of religions.

Professor Salguero, in Spain, emphasises the importance of post-secularisation, which is a dominant paradigm in the theoretical framework of religious studies.

“Post-secularisation seeks to retain all the advances of secularising modernity, but integrate them into a set of religious beliefs”, he says.

In a 2022 article on post-secularisation, sociologist Rafael Ruiz Andrés pointed out that “the debate on religion, both at academic and political levels and in the media, has become more important and visible in recent decades”.

Three years later, this remains the case, as the media's focus on evangelicalism, debates such as the Italian Educational World Jubilee, and the growing interest in undergraduate and graduate Religious Studies programmes show.

The Centre for Sociological Research (CIS) and other organisations, such as the Youth Institute (INJUVE), include a question about the religiosity of those surveyed in each study they carry out. But how is that question asked?

The question templates include the options practising Catholic, non-practising Catholic, believer of another religion, agnostic, indifferent, non-believer or atheist.

However, the distinction between practising and non-practising Catholics, which had been included in the survey since 1978, was removed in 1994 when the atheist category was included for the first time.

It reappeared in 2019 when the CIS added the option of 'agnostic' for the first time, and merged the categories of 'non-believer' and 'indifferent'.

According to Salguero, “it seems that the way surveys are conducted still has vestiges of the past, with a Catholic perspective viewing other religions as an anomaly. When the question is reworded, the figures will probably be very different because I believe that Islam and evangelical Christianity are invisible in the current CIS figures”.

“To avoid sensitivities and biased positions, I believe that including as a response option all religious denominations listed in the Register of Religious Entities, would be a good starting point for measuring reality”, he adds.

Other ways to learn about religious attitudes in Spain include the directory of places of worship, and specific studies promoted by the Observatory of Religious Pluralism in Spain.

When it comes to the situation of young people specifically, the most widely consulted data is that provided by INJUVE.

Every four years, this organisation publishes a Youth Report which includes the question, “How would you define yourself in religious terms?”, offering the same options as the CIS.

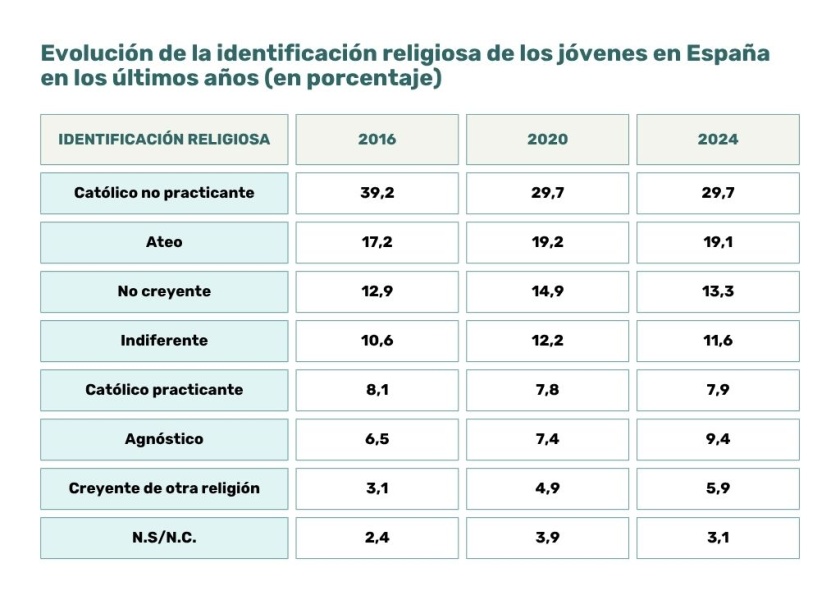

Cross-sectional analysis of data from the 2016, 2020 and 2024 reports shows a sharp decline in non-practising young Catholics (almost 10% in the last eight years) and slight fluctuations in practising Catholics. The 10% decline in non-practising Catholics has been fairly evenly distributed among the other options.

[photo_footer] Trends in religious identification among young people in Spain. / Author's work based on INJUVE data from 2016, 2020 and 2024. [/photo_footer]

According to INJUVE, 44% of young Spaniards do not identify as believers, whether atheists, indifferent or non-believers.

Agnostics (9.4%) say that 'knowing the divine is inaccessible to human understanding', while 7.9% identify as practising Catholics and 5.9% follow other religions.

Meanwhile, 29.7% fall into the indeterminate category of 'non-practising Catholic', which Adolfo Ivorra, a Catholic priest and doctor of liturgical theology, described as “a way of softening the blow, of creating a necessary fiction: the apostasy of the masses”.

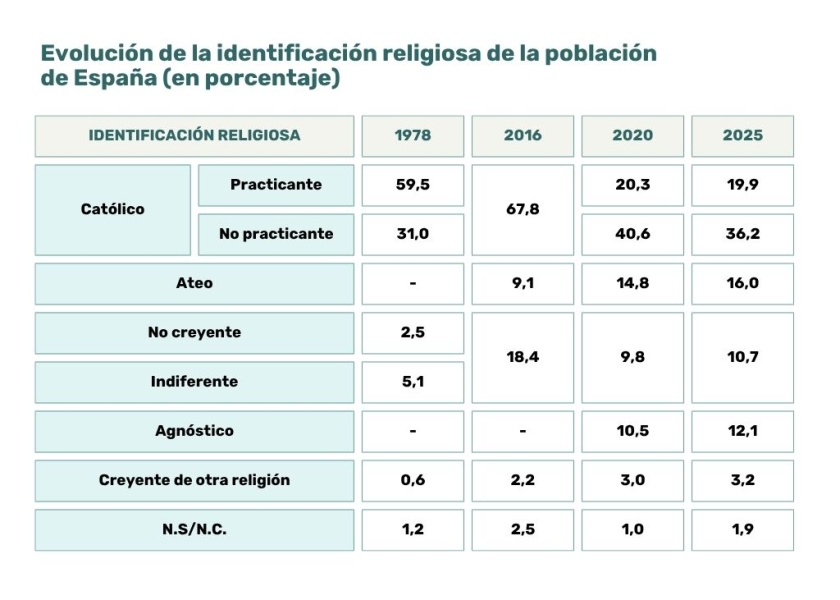

However, this trend does not only apply to young people. Surveys show that the Spanish population is no longer identifying as Catholic, with a striking decline in non-practising Catholics in recent years.

[photo_footer] Trends in religious identification among Spanish population. / Author's work based on INJUVE data from 2016, 2020 and 2024. [/photo_footer]

Although there has been a long-standing theoretical debate in academia about whether religion, religiosity and spirituality are the same thing, with little consensus, Salguero told Spanish news website Protestante Digital: “We also have to learn to look at the street” .

“Taking off my anthropologist's glasses", he jokes, “I use the term religion for more institutionalised manifestations, whereas spirituality perhaps refers to more subjective manifestations with vaguer structures and little institutionalisation”.

This distinction is most common among young people. “I don't really like the word religion because I don't adhere to any. However, I consider myself a very spiritual person because I understand that not everything has a rational explanation”, my friend Mark told me.

“I find the concept of 'spiritual' to be much more intimate and personal. It's not so much about doing or participating in something; rather, it's about having a certain way of living and behaving towards others and yourself”, said my friend Paula.

“When I think of the term religion, I think of a much more distant divinity, as if you had to go through certain procedures to connect with it”.

For Juan Pablo Serrano, the national coordinator of University Bible Groups (IFES Spain), “it's not so much an approach to religion as an approach to spirituality”.

“The type of talks that people are looking for now are not so much an academic apologetic approach, but rather an apologetic approach to the heart. People want to hear about experiences and are looking for a more emotional dimension”.

Salguero, with nine years of experience as a lecturer in the Bachelor's and Master's degrees in Religious Studies, recalls that “my first graduating classes did have a much more 'secular' outlook (agnostics, atheists...), whereas now I find people who either belong to a religious denomination—as original as Hellenism—or who, increasingly, practise a more individualised and personal spirituality”.

[photo_footer] Hakuna Group Music, a group of young Roman Catholics, performing for 25,000 people in Madrid. / Alfa y Omega [/photo_footer]

“The most vital contemporary forms of religion grow in the context of the global market”, explains the British sociologist Linda Woodhead. "In religion, one size can no longer fit all [...] there is diversification into market niches that often run across nations or even continents”.

“New-style religion is more like a business enterprise or many start-up firms. It draws on the unregulated energies of women and men, who often act individually and unaccountably, taking advantage of the low start-up costs of religious enterprises and of opportunities provided by processes of globalisation and new media”, she adds.

In that market, unaffiliated spiritualities seem to be the highest bidders.

In a study on this type of spirituality, Spanish anthropologist Mónica Cornejo Valle stated that this concept refers to what academic literature has historically called 'new forms of spirituality', 'New Age' spiritualities, or 'subjective spiritualities'.

Therefore, these spiritualities share the belief that there is a universal, generally impersonal, supernatural force that manifests itself in material reality and personal entities, such as gods and spirits.

As Cornejo points out, these beliefs have grown to “occupy the space between the major religions and anti-religion”.

In 2017, 16.8% of people in Spain identified as spiritual but not as followers of a specific religion.

This data illustrates the ineffectiveness of the CIS question on religiosity — how can so many 'spiritual' people be completely invisible in traditional figures? — and proves that, contrary to popular belief, this reality existed before the COVD-19 crisis.

In a CIS survey conducted in September 2021 on the effects of the pandemic, 9.6% of respondents in Spain said they had become more religious or spiritual.

Similar figures were observed in countries such as the United States, where 10% of adults believe that the pandemic had a positive impact on their spiritual or religious life.

However, the data is insufficient to conclude that the pandemic has motivated young people (or the general population) to become more spiritual.

However, the statistics do reveal that due to the coronavirus, 51% said they had been paying more attention to social media, a figure that rises to 73.8% and 67.2% among 18–24 and 25–34 year olds, respectively.

Hashtags such as #witchy, #horoscope and #spiritualawakening already have millions of results on social media.

Likewise, the emergence of accounts and influencers offering content related to unaffiliated spiritualities is striking.

“To say outright that social media and the pandemic have clearly affected young people's religion could imply that they have no critical judgement and consume everything that comes across their screens, without any kind of filter. And nothing could be further from the truth”, underlines Salguero.

There is a clear trend among young people, but also the Spanish population in general, to break away from what might be called 'cultural Catholicism' in order to explore other religious options.

In a globalised world where social media plays a dominant role in communication, new ways of relating to 'the sacred' have gained ground, moving away from the way religion has been understood in Spain over the last century.

The National Catholicism of dictator Francisco Franco's regime, which exploited ecclesiastical structures and elites to serve the dictatorship and rejected religious diversity, left a negative mark on the way religion is perceived by Spaniards.

That is why, after forty years of a religion imposed in order to 'be a good Spaniard', there is a suspicious view of faith among those who were born and lived during Franco's time or immediately afterwards.

However, Generation Z has a different perspective on religion. Young people in general show a more sensitive attitude towards religion because they were born and raised in a democracy, surrounded by plurality and diversity.

This new way of understanding and relating to religion cannot be captured by a general question in a survey; rather, it requires reports and studies that ask the right questions.

[analysis]

[title]How can the evangelical church respond? [/title]

[text]Based on my interpretation of the data, I believe the figures show people's desire to move away from an inherited or cultural faith, a 'dead' faith.

Young and not-so-young people alike share a desire to relate personally to 'the sacred', whether to engage with it, question it or reject it, but in search of their own answers.

That curiosity places us before a kind of 'global market' with countless religious options. What makes the difference is the way in which each religion understands, relates to, moves around and communicates in that market.

That is why, as Rafael Ruiz pointed out, a major post-secular challenge is “the creation of a truly dialogical context in which all voices, religious and non-religious, have their place and can interact freely and openly, without prejudice, at different levels”.

How do we engage in that dialogue? Jesus should be our only role model. He approached people, asked questions and engaged in dialogue, setting an example of listening, love and truth, even with those whom society rejected.

The compassion with which Jesus looked at the crowds stood out above any fatigue, discomfort or hunger they might have felt.

Where do we speak from? Do we listen with the same interest with which we speak? Do we have a dialogue or a monologue?[/text]

[/analysis]

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o