After 36 years of pastoring churches in Turkey, Carlos Madrigal was labelled a threat to national order and is no longer allowed to enter the country. He and his wife Rosa share lessons to be learned about Christian work in non-Western countries.

Carlos Madrigal and Rosa María Orriols in Catalonia, after their departure from Turkey. / Courtesy of the author.

Carlos Madrigal and Rosa María Orriols in Catalonia, after their departure from Turkey. / Courtesy of the author.

Catalonia Square, the urban heart of Barcelona, seemed the right place to meet Carlos Madrigal and Rosa Maria Orriols after their return, now to stay, to Spain.

In a prayer letter shared in February, they reported that the Turkish authorities would not allow Madrigal to return to the country after 36 years living and serving there. “We guess they are basically accusing us of proselytising”, he explains.

Orriols can still enter and leave the country and has continued to travel to visit family and churches there.

With a judicial process underway that is already in the phase of an appeal to the Constitutional Court, and with the plan to go to the European Court of Human Rights, the couple looks at their current situation positively.

In an interview with Spanish news website Protestante Digital, Carlos and Rosa talked about the situation of the church in Turkey, as well as their ministerial perspectives now in Spain and the current state of the mission.

Question. How has it been to be forced to leave Turkey now, after so many years?

Carlos Madrigal: The authorities claim an unjustified reason, arguing that we are a danger to national order and security. A dossier from the Turkish intelligence centre says that, but neither we nor our lawyer are allowed to see it.

They sent the dossier to the foreigners' office and put me on a list with a code that means I can no longer re-enter the country from the moment I leave it.

There are 80 brothers and sisters in the faith who are in the same situation, and this affects many other people, because family members usually accompany those who have been expelled. It is a tacit way of expelling missionaries.

As we cannot see what it says in the dossier, there is no way to fight it either. But yes, we guess that they are basically accusing us of proselytising.

We also know that many people have been put on that list because they were attending an annual conference organised by the Evangelical Alliance of Turkey for the families of pastors.

As the meeting was held in hotels, they took the list of participants from there, entered their names in the registers and got rid of them.

Rosa Orriols: They have also denied nationality to the foreign wives of many Turkish Christians who are not even pastors, even though after being married for three years, according to Turkish law, a person has access to nationality. But they have claimed security concerns without giving any further explanation.

There are two such cases in our churches that are striking. An American young man who is married to a Turkish woman has now been denied citizenship because he is accused of engaging in proselytising activities between 2016 and 2018.

Another man, from one of our churches in Izmir, is married to a Kazakh woman, and she, after three attempts to apply for citizenship, has received a notice saying that it is denied because her husband is linked to Protestant churches. The situation is difficult.

C. M.: In general, Protestants in Turkey are seen as a danger to state security.

Q. You do not have any reservations about taking your case to the European Court of Human Rights

C. M.: Within the country there is no hope of winning legal proceedings. Not being able to see the dossier and the defencelessness that this entails is already a violation of a constitutional right and a human right.

In order to go to Strasbourg we have to finish the legal proceedings in the country and lose and then file an appeal that is accepted.

That is difficult in individual cases, but since there are already several cases, it becomes clear that this is not an isolated case of someone who has had an administrative problem, but a government strategy to expel foreign evangelicals from Turkey.

Of the 80 people who have been expelled, about 30 of us have started legal proceedings. All of us have lost the first trial in the ordinary court, except for two who are married to Turkish spouses.

Moreover, out of those 30, about 15 of us have also lost the appeal, so the next step is the Constitutional Court. There are already three or four people who have lost again.

We appealed over a year ago and are still waiting for the result. If we win, the trial would have to be reviewed again, but if we lose, the next step is the European Court of Human Rights.

They are very subtle, they don't ban me from entering the country, because then they would have to justify a deportation. It's a restriction of entry. In the lawsuit they claim that I could apply for a special visa at the consulate, because Spaniards don't need a visa to enter Turkey, but they denied it when I asked for it.

Therefore, another lawsuit is now also open in the name of our church, that is, in this case it is an "institution" and not a private person who is going to court.

All these battles involve a lot of money, even if we have known the lawyers for years and there is an evangelical human rights organisation in Europe that partly supports us.

It is a fight that we will win or lose, but at some point it will also help to create a precedent for those who may face a similar situation in the future.

R. O.: There will be elections in Turkey soon and there could be a change of government, even if this does not mean a change of mentality. But it would be very important if those court cases were won, because perhaps a new, more open government could accept the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights. This would give a new vision.

Now, since the problem with Andrew Brunson (who was accused of espionage and imprisoned in Turkey for two years), Protestants are seen as those who are against the government.

Q: Does the problem start with that case?

R. O.: It's been going on for a long time, but this case was an explosion. Before, Protestants were frowned upon, as if they were CIA spies going to Turkey to undermine the country, but after Brunson it has been taken to such an extreme that this view seems to be the law.

C. M.: Furthermore, Andrew Brunson lost his trial. He was accused of being a spy, a conspirator and a supporter of terrorism, and he lost in court. He was released under pressure from the United States, but that does not mean that his record has been cleared.

R. O.: For them, he was involved in terrorism and the rest of us Protestants are also part of the same thing. But if we win those trials in Strasbourg, and if there is a change of government, the decisions will be accepted and, in a way, this image will be cleaned up.

C. M.: You say in Turkey that you are evangelical and the first thing they do is connect you with the extreme right in the United States, that is why we prefer to call ourselves Protestants, because the term is seen differently.

For a Turk to tell his family or the media that he is an evangelical is like us saying in New York that we are Al Qaeda members. That's the perception, they really think so.

Ten years ago, in the first church we started, there was a complaint that there was an arsenal. A special operations police group showed up in the middle of the service to search the premises for weapons.

R. O.: Before, when we went to court as Protestants, we could win because there was a separation between state and religion, and the judges understood that it was a matter of conscience and religious freedom. That's why it's very important to win these trials today.

C. M.: In fact, proselytising, understood as the propagation of your faith, is not only not banned in Turkey, but protected by the Constitution.

R. O.: But now there is another unwritten law that prevails. And when a judge doesn't understand it that way, he is replaced.

Q. After so much wear, what are your chances of a positive ruling from Strasbourg?

C. M.: I think the outcome will be positive in Strasbourg. If in Turkey, where the mentality towards foreigners remains the same, they are already beginning to see irregularities at the judicial level, I think that in Strasbourg it will be more evident.

The concern is not to lose in Strasbourg, but that Turkey will then follow the European ruling.

R. O.: It's not a wear. The last times I have travelled to Turkey on my own, there have been three rounds of baptisms and I have been able to attend all of them. I visit the pastors and they are encouraged.

Other ministry opportunities arise here as well. Since we have been here in Spain, in the last few months several people with whom we have had contact and to whom we have spoken have been converted.

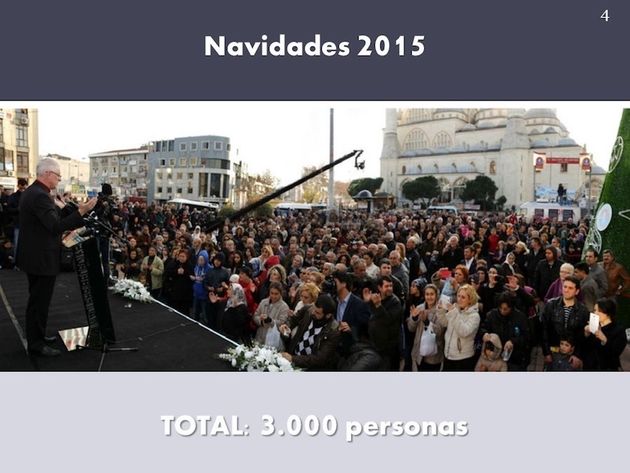

[photo_footer]Despite the rejection of Protestants, during all these years Madrigal has been able to share his testimony in several Turkish televisions. / Courtesy of the author.[/photo_footer]

Q. Then, are we talking about a new stage in Spain?

C. M.: We were already considering rotating between Spain and Turkey, so that the churches there would take more responsibility and be able to work more autonomously. The only difference is that I was planning to visit often, but in this situation I can't. We are still in contact with the pastors.

I continue to give some classes from the distance. Sometimes I also preach, the bond has not been broken and this is forcing more to take responsibility. There are new converts and new churches, who are learning and facing new situations in pastoral ministry.

I have been prevented from going to Turkey, but we have not been cut off from the work in the country.

Next year is the centenary of the creation of the Republic of Turkey and President Erdogan has always said that he is working on his project for the year 2023.

The rumours say it is to establish a sultanate. Not openly, but de facto they are already doing so, and if that takes on a more formal and official aspect, Turkish believers will be in trouble.

Q. How are minorities in Turkey affected by this shift towards religion by a state that until a few years ago was based on secular principles?

C. M.: Turkey is secular by definition, but it is strange for a secular state to have a Sunni Islamic Ministry of Religion.

There was an awareness of secularism in jurisprudence, but in practice the subject of religion is compulsory. One third of public schools have become Koranic schools and have direct access to university. There has been a whole investment in “Islamicising” the mind of the country.

Q. How is the relationship between the government and the minority faiths in the country?

C. M.: Minorities have no say in Turkey. Moreover, those who disagree are not even allowed to protest on the streets because it is considered a betrayal of the state.

Q: How has the pandemic affected the churches in Turkey?

C. M.: It has affected them much less than here. There have not been so many restrictions or such severe lockdowns. The problem was that for the first year and a half, the lockdowns in Turkey were at weekends to prevent people from travelling.

R. O.: But we were able to hold our weekly services. Since the mosques were not closed, if they could, we could. We had a special permission to worship.

C. M.: There has not been very exhaustive monitoring by the authorities or the media either. Here there was a daily flood of information and during that time we held online meetings, but now it is back to normal.

However, there have been many deaths in the country. It affected us because we were in a situation of uncertainty an we could not move between provinces.

Q: Has the war in Ukraine had an impact?

R. O.: The economic crisis, yes. There is a very high inflation, prices are on the rise but they are trying to keep the currency down. As a result, a country that used to be much cheaper than Spain, now the shopping basket is more expensive than here.

C. M.: Turkey was much more affected by the conflict in Syria. Firstly because it has interests in Syria and many refugees have ended up in Turkey, but also because it is a neighbouring Muslim country, while Ukraine only shares a maritime border.

On the other hand, Europe has ignored the problem in Syria. Ukraine seems to be the first war to break out. Everybody has supported Ukraine because it is a Western, Caucasian, Christian country that wants to be part of the European Union.

Here in Spain it is affecting economically, but Turkey is not fighting against Putin and is not supporting Ukraine militarily, so that it doesn't affect it as much as it does here.

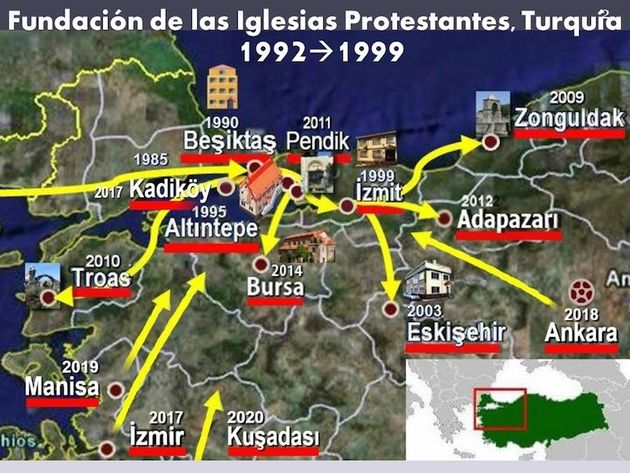

[photo_footer]Map showing the churches that Carlos and Rosa have established in the northwest part of Turkey during their ministry in the country. / Courtesy of the author.[/photo_footer]

Q. Without forgetting the bond with Turkey, what is your ministerial perspective from now on?

C. M.: We are already quite established. I collaborate in our church in Barcelona, and also visit other congregations, not only to preach and share our ministry, but also to promote the missionary vision.

I am part of the Spanish Missions platform, launched by the Spanish Evangelical Alliance with the aim of encouraging the commitment of the church in Spain to missions.

I also teach several courses, especially for people focused on the Islamic world, both here and by distance learning, in Latin America. In fact, I have been invited to missionary and pastors' conferences in other countries.

I am in contact with the Arab church here and I am writing some material. I have some materials written in Turkish and I would like to translate them into Spanish.

We are witnessing and discipling people we know. But our heart, apart from continuing with the bonds and supporting the church in Turkey, and even if it is possible to raise support from Spain, is to promote the missionary vision.

Within the Spanish Mission platform our desire is to help churches to understand that mission is not something else, nor something that for a long time has been given to us from outside, but rather it is the very DNA of the church.

Mission does not diminish the church, it does not take away resources or strength, but rather it adds to it. The goal is to create mechanisms so that those who would like to go out in the future can prepare themselves, have support and pastoral care. We are working hard to lay the foundations.

We visit the churches that call us. It is good to see there is a new era in Spain related to missions to other cultures.

Q. You have been in Turkey for 36 years. How did you find the situation of the mission in Spain?

R. O.: Before we went to Turkey we found receptive people. After we left, as time went on, every time we came back, we found that the people were not receptive to the gospel at all.

Now, this last time, we have found that people are receptive and we can talk about the gospel. In a short time, we have seen four people converted, including one Moroccan. Covid-19 has encouraged that scenario because, in a way, people have felt very lonely.

I don't think people are closed. There is a great opportunity for evangelism, and since there are people from many cultures, many cultures can be evangelised. Ideally, the church in Spain would take advantage of this opportunity.

C. M.: In Turkey, the culture is very relational, whereas here life is more compartmentalised. On Sundays we go to church and during the week we are at work.

But we have found a lot of passion for the missions, which didn't exist when we left. It is true that now there is secularisation and some ideological agendas that make us self-conscious, but when we left, the church in Spain had a bit of a ghetto complex, and in a way it still does.

In Turkey, the church is very aware of the problems and threats it faces, but it doesn't have a ghetto complex, it is more outspoken.

It seems that in Spain, the churches live in their evangelical subculture. In Turkey, because evangelicals are not accepted by society, they live more in a symbiosis, people are not enclosed in their own religious life and feel that the world is outside.

We should talk about our experience as believers in a natural way, not go hunting. We don't talk about a set of religious precepts, but share our relationship with Jesus.

Everyone is aware of the faults we have, and obviously it must be made clear that there is a problem called sin, but now we must stress that we are not complete without Jesus. Jesus met with tax collectors and sinners, the ones he told most clearly to repent or they would perish for their sins were the religious.

There are issues that have had a lot of weight and importance in our European culture, but we are stuck with the agenda of how to explain the gospel of the past. That is not wrong, but perhaps we should not start from there. Jesus' way of approaching people was very versatile and flexible.

R. O.: We are not saying that you should not tell people that they have to repent of their sins, otherwise they cannot be converted. But before that you have to make a process so that people can come to Jesus and see that he is real; in fact, that is what they need, because everybody has problems and lives with misery.

Q. How have you dealt with the cliché of the foreign missionary arriving in another country?

C. M.: Turkey is a very nationalistic country and the population always emphasises the differences between the locals and the foreigners, not so much because they are evangelicals.

One of the keys is obviously the language, but the other is with whom the missionary forms his circle.

The problem with some missionaries is that they have their circle of relationships with other missionaries and understand ministry as their working hours, in a very compartmentalised way, creating isolation themselves.

When I talk about a circle, I don't just mean relationships within the church. We used to go on holidays with Turkish people, our friends were Turkish, our children have studied in Turkish universities. I remember that while we were in Turkey we did not celebrate any typical Spanish holiday.

The missionary cannot simply be present and remain attached to the culture of his country. Unfortunately, there are some who have the desire and the will to serve like that, but they are unable to do so because culturally they have not been structured to know how to assimilate other things.

[photo_footer]Carlos and Rosa, during their farewell to Turkey, with a portrait of the founder of modern secular Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, behind them./ Courtesy of the author.[/photo_footer]

Q. How has the missionary scene changed since you started?

C. M.: When we started, missions were met with indifference or, rather, disbelief. Today it is welcomed wherever it comes from. That is something that has changed.

However, the church at this point needs to become aware and create connections, rather than structures, which are already formed. Ties between all the churches and groups that are working in missions so that people can go out.

The mission is not just a matter of taking the plunge and leaving, there is a whole process that requires knowing how to arrive in a country, obtaining a residence permit, learning the language, adapting to the culture and having a background on how to deal with another religious reality.

Moreover, it is also necessary to know how to care for, sustain and support the mission. It is necessary to articulate all that.

We at the Spanish Mission platform do not seek to create structures that do this, but to be catalysts, to get in contact with all those who are involved in mission programmes and to make ourselves available to the people of God by showing them what can be done.

In our case, we speak from experience because we have been able to carry out the work in a difficult country. We left under difficult conditions, but the Lord has done much more than we could have imagined.

Q. The 'emptied Spain', immigration of Islamic origin, etc. With the missionary challenges here, why would you think of going abroad?

R. O.: That is the question they asked us when we left. And the answer is still that there is more need in Turkey than in Spain. We went to Turkey because then it was the largest and least evangelised country in the world, and it still is.

C. M.: When we arrived in Turkey, there were 30 Protestants out of 62 million inhabitants. In Spain there were 36 million people, and it was said that there were between 250,000 and 400,000 evangelicals.

R. O.: In Spain, maybe others can meet those needs, but not everyone can go to Turkey. The Lord called us to go to Turkey.

C. M.: Whoever is really concerned to bring the gospel to the other cultures here, to his neighbours or to the emptied Spain, will have a heart to which the Lord will also speak of the needs of others.

Q. What role has discipleship played in your missionary development?

C. M.: Sadly, in the evangelical world, discipleship is seen as a series of intellectual, doctrinal and academic teachings in a church or seminary setting.

But discipleship is a formation of character, values, principles and patterns of behaviour. And that is not done through teaching programmes, but by living day to day with the person, encouraging and correcting them and also providing a biblical education, obviously.

In Turkey we have noticed that within the missionary movement there is academic discipleship, but there is a great lack of character discipleship.

We have done this by giving as much academic and doctrinal equipping as the people have been able to take in, but above all we have lived their situations on a day-to-day basis. We have mentored and taught them in such matters as economic stewardship, moral purity, criticism and spiritual disciplines.

That is what Jesus did with his disciples. Discipleship is more than a programme, it is forming the mind of Christ in the person. It is not fighting to know when Jesus will return, but reconciling with one's brother (for example).

R. O.: I think it is a little easier in Turkey than here because there is a very home culture there. People meet and visit each other in their homes and the relationship is much more personal, so it becomes a natural process. Here it seems to require more effort.

Q. The so-called 'Global South' has been gaining weight on the mission scene. To what extent can there be a reversal of the typical 'West to the rest of the world' framework?

C. M.: There is certainly a movement of the Holy Spirit and of God's people in all countries towards other countries.

Latin Americans, Africans, Asians, in general, when they go to another country where Christianity is already established, they end up establishing ethnic churches, partly because they may feel displaced, like for example the Korean church in Turkey.

But when they go to countries where Christianity is not established, they form a general church. We need to take advantage of a movement like this to reach out to the unreached countries, which is where they are going to fit in better and where they have more to bring, rather than going to Canada or the United States, for example.

Another very serious problem, which almost nobody tackles, is that the Global South depends financially on a very high percentage of the Global North, which is why the Global South is reproducing the patterns, vices and defects of the Global North when it comes to carrying the gospel.

We have to fight hard to break those bonds of dependency, or establish them in other terms.

The Global North seeks methodologies, while the South seeks relationships. Therefore, since the North, in general, does not know how to build relationships, it needs methods, and when one method does not work, they look for another method.

I have heard people praying for revival in Turkey, but for there to be revival, there must first be a dormant Christian culture. People say that because in the countries that are heirs of the Reformation the gospel has spread through revivals, but they forget that in countries that have no Christian background, the gospel has spread through evangelism and missions.

We can spend our lives praying for revival, but if we do not preach the gospel, we have nothing. It is good to pray for a harvest, but he who prays for a harvest must sow.

R. O.: There are countries like Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan or the territory of Sinkiang [China] where there is a large Muslim population, but they are very open people. They have Turkey as a reference, I hope that God will raise up people to go there.

C. M.: But in order to do that, first you don't have to do what the mainly Anglo-Saxon or Scandinavian missionaries have done in Spanish-speaking countries. They formed a leadership with the vision to reach the countries they went to serve, but they did not pass on to the national leaders they trained the vision that brought them to those countries.

That is why in Latin countries we have had to re-discover or re-invent the wheel. There is no culture of missions.

We have to be very careful not to make that same mistake in countries like Turkey.

[donate]

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o