According to archaeologist Douglas Petrovich, inscriptions in stone slabs from Egypt contain an early form of Hebrew, with references to figures from the Bible.

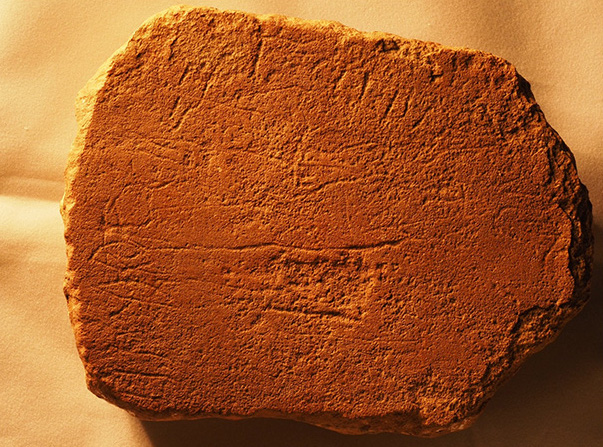

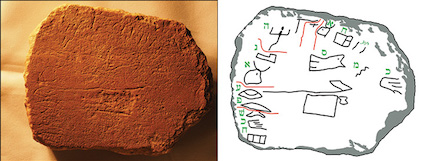

One of the 16 pieces, dated to 1834 B.C., translated by Petrovich.

One of the 16 pieces, dated to 1834 B.C., translated by Petrovich.

Douglas Petrovich, archaeologist and epigrapher of the Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo (Canada), is proposing an innovative reading of several inscriptions on Egyptian slabs from the 18th to 14th centuries BC. These slabs could be the first "alphabet" in the world, an early form of Hebrew with data that coincides with some contents of the early books of the Bible.

On November 17, at the annual meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR), Petrovich stated that Israelites living in Egypt transformed the civilization’s hieroglyphics into "Hebrew 1.0". That would have happened more than 3,800 years ago, at a time when the Old Testament describes Jews living in Egypt.

Hebrew speakers, seeking a way to communicate in writing with other Egyptian Jews, simplified the pharaohs’ complex hieroglyphic writing system into 22 alphabetic letters.

“There is a connection between ancient Egyptian texts and preserved alphabets”, Petrovich said.

An inscription, dated to 1834 B.C., translated as Wine is more abundant than the daylight, than the baker, than a nobleman. The inscription across the top says: The overseer of minerals, Ahisamach.

An inscription, dated to 1834 B.C., translated as Wine is more abundant than the daylight, than the baker, than a nobleman. The inscription across the top says: The overseer of minerals, Ahisamach.Petrovich's thesis allowed him to translate some inscriptions that until now had no interpretation. He combined previous identifications of some letters in the ancient alphabet with his own identifications of disputed letters, to peg the script as Hebrew. Then, armed with the entire alphabet, he translated 18 Hebrew inscriptions from three Egyptian sites.

Several biblical figures turn up in the translated inscriptions, including Joseph’s wife Asenath and Moses, who led the Israelites out of Egypt. In the inscriptions across the top “The overseer of minerals, Ahisamach” is also mentioned. Joseph only appears in ME (Middle Egyptian) inscriptions.

Douglas Petrovich.

Douglas Petrovich.An inscription, dated to 1834 B.C., is translated as “Wine is more abundant than the daylight, than the baker, than a nobleman.” This statement probably meant that, at that time or shortly before, drink was plentiful, but food was scarce, Petrovich suspects. Israelites, including Joseph and his family, likely moved to Egypt during a time of famine, when Egyptians were building silos to store food.

Petrovich is aware that his study will be controversial. Many specialists argue that, despite what is said in the Old Testament, the Israelites did not live in Egypt as soon as Petrovich proposes it. The biblical dates for the Israelites' stay in Egypt are not reliable, they say.

A book that Petrovich promoted through a crowdfunding project (detailing his analyses of the ancient inscriptions) will be published within the next few months. Petrovich says the book definitively shows that only an early version of Hebrew can make sense of the Egyptian inscriptions.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o