The coordinator of the project that published the first images of a black hole, speaks to us about his scientific work and how the Christian faith has influenced it.

![Heino Falcke, coordinator of the Event Horizon Telescope project, which in April 2019 presented the first image of a black hole. / Photo: Boris Breuer, [link]Heinofalcke.org[/link].](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/61a9ecfdca657_heinofalcke940bCropped.jpg) Heino Falcke, coordinator of the Event Horizon Telescope project, which in April 2019 presented the first image of a black hole. / Photo: Boris Breuer, [link]Heinofalcke.org[/link].

Heino Falcke, coordinator of the Event Horizon Telescope project, which in April 2019 presented the first image of a black hole. / Photo: Boris Breuer, [link]Heinofalcke.org[/link].

It is strange to look up at the sky again after seeing the image of the black hole at the centre of the M87, a galaxy 55 million light years away from us, surrounded by a ring of light a hundred billion kilometres in diameter.

This photograph, released on 10 April 2019, is the result of an international collaborative project with the Event Horizon Telescope, which was coordinated by a member of the Dutch Protestant Church.

The astrophysics researcher and professor at the Radboud University in Nijmegen, Heino Falcke (Cologne, 1966), described the process of working towards the image in his book Light in The Darkness. Black Holes, the Universe and Us.

Falcke also uses a great deal of space in his work to speak about the spiritual concerns that motivate and influence him as a scientist.

“When you really write about deep fundamental scientific questions, when you write about the Big Bang, or about the black holes... How can you not ask about what is underlying and where does it come from? How can you not ask about God?”, said Falcke in an exclusive interview with Spanish news website Protestante Digital.

The brilliance of his work, recognised with the prestigious Spinoza Prize in 2011, is complemented by a friendly and joking character in our interview. We spoke an autumn afternoon of 2021, when the stars still seemed as distant as usual, and our smallness went unnoticed in the face of the great immensity that surrounds us.

Question. What is life like after being the first person to take a picture of a black hole by coordinating a worldwide project?

Answer. There is a life before and after. It did change my life and that of many others. This picture was made by an entire collaboration. I was not the only one, but indeed, I was someone who inspired this work.

I had this dream 25 years ago, but in the end it was a big collaboration of many people. We went together to make this image happen in very turbulent times.

Before there is uncertainty, there is anxiety, there is expectation. There are dreams that suddenly became a reality. And then there was a transition phase where the dream was sort of real but it wasn’t yet shared. We had the image with ourselves for a little while. Then it was shared with the world, and was suddenly public and was everybody’s knowledge. That was the most emotional moment.

And now you see the picture quite often when a black hole comes up, when people illustrate black holes all over the world. First, we saw it in almost all the newspapers and news websites, and now in text books. It became an iconic picture.

Since I was the one revealing it in Brussels, I received some visibility also for myself, of course. Now I see that my role and my identity shifted a little bit. I’m now the one of that black hole picture. And that gives you opportunities, but also responsibilities.

People want to listen to what I say, they are interested, they read the book, they ask for lectures. In the Netherlands, the Protestant Church has asked me to give their annual lecture. They have a thematically lecture once a year and they ask it a prominent person to give. They had the prime minister last year, and now they ask a scientist to do it.

It means that suddenly I’m reaching a much broader audience than before but I am also being asked about a much broader range of topics than before. That is good. I think that my own background as a preacher helps because I have been talking about basic topics of life, faith, society before, and that was a good training as well.

[photo_footer]Image of the black hole at the centre of the M87 galaxy. / Event Horizon Telescope, Wikimedia Commons. [/photo_footer]

Q. What's the next 'celestial object' on your list?

A. We do have a clear plan. We still have a picture of the center of the Milky Way that we need to publish. We have the data. It’s going to be a very important work. Scientifically, maybe it’s more important than the other one because it’s the center of our Milky Way and it has been explicitly well studied. There is a clear prediction of what we need to see.

This is an important test of the theory of black holes and general relativity. We need to stand on two legs. For now we have one black hole, soon we have another one and then we will see if we stand or we fall. In science, the confirmation is as important as the first experiment, so we are very nervous about this one, waiting for it.

In the closer future, the next couple of years, the next ten year... we want to make movies. We have now one picture but we need many for the videos.

[destacate]“We have the data of a picture of the center of the Milky Way ready. It’s going to be a very important work”[/destacate]Material is flouting around black holes and these are also able to shoot out material - not everything disappears in the black hole. Some of the material manages to escape before falling in the black hole and is seen as powerful plasma jets, just like science fiction.

These jets are shooting out of the center of the galaxies and that is something that we want to see in action. Eventually, we want to see a color movie of black holes.

And then, in the very far future, we may want to go to the space and build a telescope larger than the earth, so that we will get high resolution and movies of many black holes: throughout the entire universe. But all of this will require a lot of patience, discipline, hard work, collaboration and endurance.

Q. I cannot wait to see that movie.

A. It will be strange at first, as usual, but it will get better with time. We have already made a little spoiler. The first image was actually much better that even we had expected and we cannot always be so lucky.

Q. In your book you stress the importance of having achieved not only the image, but also creating a joint work project with many people from around the world. Do you think this project has set a precedent in the world of radio astronomy?

A. Global collaboration is becoming more and more important in science. We see that in particle physics.

What makes this one special is that it is really global. We have people form Asia, America, Europe but also some from Africa and Latin America. Almost the entire globe was involved in some way in this project. We needed that.

Some projects need global collaboration and it can work if we all have a common dream. Of course it’s not easy, because everybody has their own cultures and their own ambitions, and it’s not always 'one big happy family'.

If there is a specific challenge and if it’s really needed, people can pull together and make the seemingly impossible happen on a worldwide scale. But there is always a tension between collaborating and competing, so that I would call it a competitive collaboration. People want to be better than the others but they also need to work together. I think it produces a creative tension, but it can also be stressful sometimes.

Q. It is becoming less and less common in Europe to find books about God from general publishers. Why did you decide not to focus on just explaining your discovery of the black hole M87 but also to offer a precise reflection on your Christian faith?

A: There are two answers. First, I think a book is always more interesting if you learn something about the person behind it, and when I talk about my fascination of science it’s almost impossible for me to hide my fascination with God and with the big questions of the universe.

[destacate]“When I talk about my fascination of science it’s almost impossible for me to hide my fascination with God and the big questions of the universe”[/destacate]I was driven into science because I want to know what we don’t know and go to the limits of what we know. That is why I’m working on black holes, because they really represent a key limit of knowledge. And it is the same with my faith.

My faith draws me to the big mystery of God and where universe came from. I would rather say how can you not write about these questions? When you really write about deep fundamental scientific questions, when you write about the Big Bang, or about the black holes... How can you not ask about what is underlying and where does it come from? How can you not ask about God?

I think this is something that we have lost. Many of the scientists that we rely on today, who have contributed to the big results in science in the past, were driven by their faith as well. But we keep forgetting this. It was normal at that time, and that is why we forget it. We read our text books about Newton, Galileo, Keppler, Copernicus, and we don’t realise they all were deeply faithful people. For them, science and faith were very related.

My publisher in Germany also encouraged me to do it, because they were publishing the last book of Hawking and he answered the question of God in a very agnostic, or even atheistic, way, so that they asked me to present my view which maybe is sort of a counter view to Hawking.

My publisher thought this is what people want to hear. They know this book will generate interest in people and we have so many scientists who don’t talk about it. So, in that sense my view was a bit more refreshing and different.

I saw that people were really interested. So the short answer would be because people want to know. They ask. Why should we then keep quiet?

Q. You wrote the book with the help of the journalist Jörg Römer, who does not share your Christian worldview. How has this work process been?

A. We had a very good discussion about it. He, as a journalist, was very curious and made many questions. I think that if you are curious about each other and you inquire about it, and have an open mind, and you know and trust each other, there can be a constructive collaboration.

Maybe people should pursue this more. Maybe more pastors should write a book along with an atheist, because this tension can make them more accessible to others. You don’t just write for those who know everything already. You talk to a broader audience.

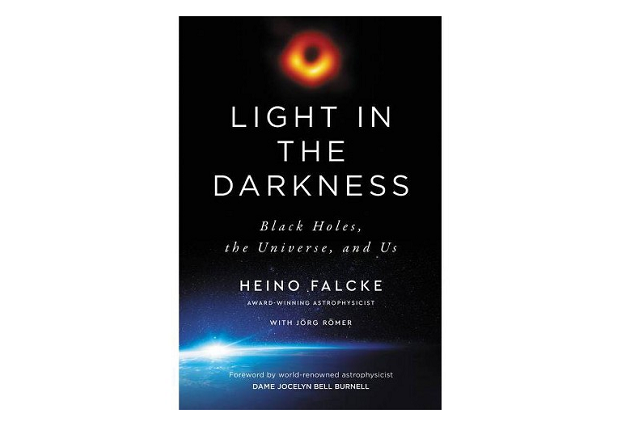

[photo_footer]Book cover of Light in The Darkness, by Heino Falcke.[/photo_footer] Q. What are some of the most curious comments and interactions you have received after publishing the book?

A. Amazon Germany rated it very high and many people appreciated it. But there are some who don’t like the book at all. One person complained I talk too much about my “Catholic worldview” and my “Catholic dogmas”. Actually, I’m Protestant and I just included a few Biblical verses in the book. Only the final few pages really talk about God. For some people even that little bit was too much.

But there are also moving experiences. A nine year old girl who was on primary school told me she had read my book twice and she was so fascinated that she decided to be an astronomer and she wanted to take the book to school to present it to others. But the teacher told her that it was too advanced for primary school. Later she came to one of my public lectures and had brilliant questions about black holes. By then she had read the book four times.

Another reader was a ninety year old retired physics teacher. He had read the book and wrote to the publisher because he want to have the picture of the black hole. He said that this was the last thing he wanted to see.

Many pastors and Christians were also very happy that I was naturally talking about my faith and for them the book was a sort of relief.

Q. In the book you say that the secret of the image is not in its ring, but in its shadow. What thoughts about the human being has brought this conclusion?

A. In the case of black holes, it is the absence of light that defines what it is. When you look at it and you understand the physics and the story behind it, you literally are drawn into it like the light is drawn into this darkness.

[destacate]“Technology allows us to look at this gorgeous universe, but it also tells us that we never will be able to conquer it”[/destacate]It’s a scary place because this is sort of the ultimate destruction, the ultimate prison that you never get out. It does remind you of death, of destruction.

That's why I use the example that we are figuratively looking at the “gates of hell”. This came from an artist that I met twenty years ago before the image was made. She was painting pictures of astronomy based on a presentation I had previously given. When I talked to her about black holes, I asked if she would make pictures of them. She said she could not because they reminded her of hell.

I think it's good for people to look at the beginning and the end, to see and face the end. For Christians there is no reason to be scared because we naturally think about Alpha and Omega, the beginning and end of the world. We think about life and death regularly and we are ultimately not afraid of it because we know everything is in God hands. That is why I think we can look at everything in the universe.

Of course, sometimes we are afraid if we are standing in a dark valley, but ultimately deep down we do not fear because we have the feeling that we are in God's hands, even in death. Or in a black hole.

That is also why Christians should fear science. It’s part of God's creation. We have to engage with science and not see it as an enemy. It is something which has been given to us by God, and God can also speak through his creation. Just look at Psalm 19:1 - even the heavens declare the glory of God.

Q. You also say that expansion means that we cannot even think about seeing most of the universe. For someone who has worked so hard to show the world that image of the black hole, what does this make you feel? Why is there such a large and and yet unknowable cosmos?

A. I think it makes you humble. We can look at all this beautiful and gorgeous universe, but the same technology tells us that we never will be able to conquer it entirely. We will never be able to personally go there or to see every bit of the universe. There are limits of what we can see and experience. The science that gives us that almost almighty power, also limits our power and tells us that there is something much bigger out there.

From a Christian perspective, it’s God letting us see some of his glory but also telling us we never reach even a tiny bit of that great grandness, beauty, and glory. I think it’s a big grace that we are allowed to see this. Maybe it is a taste of heaven. We are allowed to see a bit of the universe, but we don’t own it.

Q. We are now seeing a competition between tycoons to reconquer space by establishing the first colonies outside the Earth. Does this seem realistic to you?

A. I am in favor of human exploration of space. I think we have been sent into all areas of the world and it is a natural extension that we as humans go into space. However, I’m very sceptical of the ideas of people like Elon Musk who say that our destiny and our salvation is in the outer space.

It almost has a religious feeling and sounds like we have messed up earth, so that now we have to find our salvation in outer space. I think that is complete nonsense. As one of my colleagues said, living underground after nuclear war or a climate catastrophe on earth still has to be much more pleasant than having to live on Mars as a society.

I think we can live there like we can do it in Antarctica. Nobody wants to live in Antarctica for their entire life. We have a telescope in Antarctica and people were there for half a year. It was an adventure but I haven’t found a colleague yet who says there is where he wants to be and raise his family.

Maybe there will be some colonies on Mars or on the Moon eventually, for some very special types of people. But this is not for the world as such. Moreover, right now it’s for rich people and they determine who goes and who doesn’t. That is not the world we should strive for.

[destacate] “We don’t know if there is more life out there. It is a privilege that we are allowed to live on this planet[/destacate]Q. Many voices have referred to the universe as ‘dark’ or ‘bleak’. How do you see the reflection of the God of the Bible observing the universe? A. The universe is vast. It’s indeed mainly dark but there are islands of light and life. We are on one of those islands. For the believer, the greatness of the universe is a symbol of an even greater God.

I think the darkness, and all of these planets, remind us how special and rare life is. We don’t know if there is more life out there. It is a privilege that we are allowed to live here, on this planet. It makes me thankful for what we have.

Q. You wrote your book based on conclusions that still raise debate among some Christians, such as the age of the universe, the way it was created or the idea of expansion. How do you perceive these debates within the Christian context?

A. At least in Germany, even in the church, this is not a big question. This is more an anglophone thing. I have talked with Baptist ministers in Germany and many of them accept an old world. I think that is backed up by the reading of Genesis.

I think the problem was that around few hundred years ago, people applied the scientific and the mathematics method to the Bible and tried to extract the age of the universe from the Bible. We have to make some assumptions about this. We even know that one day in God’s view are thousand years for us. We are constantly warned in the Bible that we should be careful with mixing God’s size and times with ours.

That’s why I think that using the Bible to draw scientific conclusions from it is the wrong approach, unless you are God. This is not what it was written for. We cannot use the Bible to build an airplane. If the only book that an engineer has read in his entire life is the Bible, I would not fly on that airplane.

The Bible is an amazing book, but God has written a second ‘book’, his creation. And we can read this book and look into it. It reveals certain truth that we can use to do science and to learn something about God himself. You will understand the Book of the Word much better, the better you understand the book of creation.

This is in line with the prophets, who said that the children of Abraham will be more than the stars in the sky and the sand in the sea. It speaks of a countless vast universe. It seems to me that prophets knew about this greatness and the fact that this goes beyond anything we can imagine. We should not put the universe into small boxes.

A six thousands years universe is a small universe, a human universe. It is not a Godly universe. I think the universe tells us that God’s creation is much more bigger.

[destacate]“Because I trust God, I believe that the world I see is also trustworthy”[/destacate]When a scientist looks at the stars and measure these things, it’s obvious for him that the universe is old and big. We have measured the distance between Andromeda and the Milky Way, and it’s 2.4 millions of light years. We know how far away it is and how fast light is, we know that the light we see must come from millions of light years old.

The only way that this could not be the case is that God would purposely mislead us, that he made a universe that looks old but isn’t. I hear this from some physicists. They think that, in fact, our universe is not real, it is just a simulation, like a computer game. They say God made a universe 6.000 years ago and we can not disprove it scientifically.

The only reason why I cannot believe this is because I trust God. I believe that he is a trustworthy God that is not lying. Because I trust him, I believe that the world I see, that he made, is also trustworthy.

Q. You write: “A personal God does not seem irrational to me”. How has this idea influenced your work as a radio astronomer?

A. This belief that God is someone comes from my life experience. Not as a scientist, but as someone who seeks God. Of course, it is based on a tradition of reading the Bible and realizing that the Bible actually contains a lot of truth and experiences that people have had.

It is beautiful to see that today I can still share the same spiritual experience of a personal God with people from the history. Some of their stories are written in the Bible. That means that when I look at the universe, I think I never forget the people in this universe.

Scientists sometimes forget the human or spiritual aspects because we talk about the earth and the universe and on this scale human become insignificant. Particles don’t have feelings.

My faith reminds me what it means to be human. My science sometimes does not. That is an important correction to have. And it is also important to know that in the end all that matters is my relation to God and Jesus. Is not the success in science that makes my life successful, but my relation to God.

[donate]

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o