Wes Craven, who recently passed away, was brought up in a strict Baptist church. He received a Christian education, which he rebelled against in his youth.

Craven had a strict Baptist education, he was not allowed to go to cinema.

Craven had a strict Baptist education, he was not allowed to go to cinema.

The director of horror films, Wes Craven, who recently passed away, is probably one of the most famous graduates of the evangelical university of Wheaton College, alongside Billy Graham and John Piper. The author of “A Nightmare on Elm Street” and the “Scream” saga grew up in a Baptist family that was so strict that his parents wouldn’t let him watch films.

Born in Cleveland (Ohio, 1939), Craven grew up going to a church where smoking, drinking, playing cards, dancing or going to the cinema were strongly frowned upon. When Wes was just five years old, his father died while working as a docker for a company that constructed aeroplane parts. He drank and had recently abandoned his family. Craven’s mother threw all her energy into educating her children fuelled by a strong suspicion that the world outside the family home was full of chaos and sin.

Caroline Craven ran her house like a totalitarian state where the flow of information was closely monitored. Order was based on severe rules, and obedience was ensured through threats of punishment. Wesley was the youngest and there was nothing that he feared more than his mother’s disapproval. That fear was to haunt him for the whole of his life, even when he was married and had his own children.

Fighting sin was an all consuming battle for the Cravens, requiring constant vigilance. Everything was full of danger, but the greatest taboo was the one surrounding sex, which like any adolescent, fascinated Wes. He went to church almost every day and he also went to a Christian school. He was the only son to be able to go to University. His sister’s boyfriend studied at Wheaton College, but his mother thought that it was too liberal. It was only after many arguments that he ended up going there.

WHEATON COLLEGE

Craven studied at Wheaton College from 1957 to 1963. He lived in a student residence that had just been named after the missionary Nate Saint, a Wheaton alumnus who had been murdered the year before by the huaoranis – then known as the aucas – in the jungle of Ecuador. This was, by the way, the home country of the theologian René Padilla, who was another of Craven’s contemporaries at Wheaton. John Piper enrolled a year later. At the end of his time there, he shared a house on the Dean’s street, where people were always playing the guitar.

Wes majored in literature and psychology. He was the editor of Wheaton’s literary magazine, Kodon, until he got into trouble in 1962 for publishing a story about a love story between a white man and a black woman, and another story about an unmarried pregnant girl. As he said in an interview with the magazine People in 1989, the Dean of the university went as far as to denounce him from the pulpit. In answer to this, he starting editing another magazine outside campus entitled Courageous Sons.

At Wheaton, one of the many things that were not allowed was going to the cinema. In his last year of university, Craven went to another city to see Robert Mulligan’s amazing “To Kill a Mocking Bird” (1962), based on the book by Harper Lee. According to his interview with the Times in 2010, he could have risked expulsion, but he was in the midst of his rebellious stage.

The rules at Wheaton did not change until 2003. Nowadays some dances are allowed, as well as the private consumption of alcohol and tobacco by the staff, teachers and post-graduate students. However, this is not a sign that it has become any more liberal, but is rather the result of an Illinois State law which it has been obliged to apply, following various appeals. In 1991 the right to privacy was recognized outside working hours, preventing the College from continuing to issue a “declaration of responsibility”, which has been replaced by a “community pact”.

PROFESSOR OF LITERATURE

During his first year at Wheaton, he suffered serious damage to his spine, which paralysed him temporarily from the waist down. He spent two months in hospital. There he met a red-headed nurse, Bonnie Boecker, who had also been brought up in a strict evangelical environment. When he graduated from Wheaton, they started going out while he studied literature at the John Hopkins University, together with a Baptist deacon called Elliot Coleman, who encouraged him to write but also to break up with Bonnie. However, after years of obeying their parents and avoiding sin, the couple decided to elope.

In 1964, Craven found work as assistant to a literature professor in the small city of Pennsylvania. Work would later take him to Clarkson College of Technology in Potsdam, New York, where he discovered the films of Bergman and Fellini, the plays of Becket and the folk music revival. He directed a performance of Sartre’s play No Exit, in which the characters are locked in a room, forever.

Craven is one of Wheaton's most prominent graduates, alongside Billy Graham and John Piper.

Craven is one of Wheaton's most prominent graduates, alongside Billy Graham and John Piper. When trying to seek out his identity, Wes found himself married with two children, while his friends were bohemian students with no responsibilities. His mother would visit him regularly, bringing him food, cleaning his house and washing his shirts. He wanted to make her happy, but he rejected everything that she stood for. He felt increasingly confused and depressed, full of anger and resentment. “When you're raised to be within such rigid confines of thought and conduct, what that does to a person is you think you are terrible if you violate the rules”, he told Jason Zinoman for his book Shock Value.

At one point, Craven decided that he wanted to live in an abandoned house but, when Bonnie refused, he took off for a week and decided to travel across the country on a motorbike. This was the time of “Easy Rider”, the film that epitomized the new Hollywood of the 1960s. When he returned home, he left his job and in the summer of 1969 he moved to New York, where he faced serious economic difficulties. He started working as a taxi driver and gave classes at a high school, but he was unable to support his family, which he ended up abandoning. He no longer had his mother’s faith, but hell appeared closer than ever.

PORNOGRAPHY PIONEER

The following spring, his life took a roundabout turn when he started producing pornographic films under a pseudonym. At the end of the sixties, pornography was screened in small semi-clandestine cinemas. It was under President Nixon that the industry developed, forging links with the mafia, and enabling the screening of hard porn in normal cinemas – as seen in the film Taxi Driver –, and the creation of a network of studios. Everything began with the introduction of a series of fake documentaries which, in the name of sex education, introduced explicit sex scenes in commercial films.

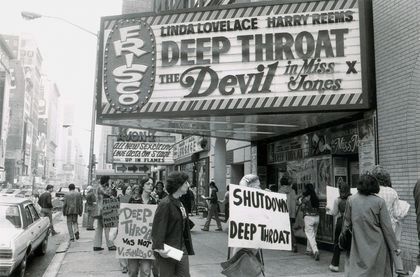

Craven was introduced to this world by his friend Sean Cunningham, who would go on to direct the film “Friday the 13th”. Before turning their hand to horror films they both worked in the pornography industry. Wes participated in the film which created the greatest scandal in those years, “Deep throat”. He talks about it in a documentary that analyses the series of legal cases brought against the film after its legal screening in New York in 1972, and the obscenity rulings handed down by many States.

The director participated in the production of controversial movie Deep Throat (1972).

The director participated in the production of controversial movie Deep Throat (1972).The main actor in “Deep Throat”, Harry Reams (1947 – 2013) had previously acted in an evangelical film, “The Cross and the Switchblade” (1970). Arrested by the FBI in 1974, Reems became the first person to be brought before a federal court for appearing in a film. He left the pornography industry in the 1980s and, after many years of drug addiction, he converted from Judaism to evangelical Christianity. Using his real name, he worked as a real-estate agent to support his family, becoming a faithful member of a small church that knew nothing about his past.

His partner in the film, Linda Lovelace (1949 – 2002), also rebuilt her life following her conversion. In the 1980s she was a mother who took a stand against the pornography industry. She said that she had participated in the film at gun point – which as not true, although she was abused by her husband. She later turned against feminism, saying that she had been used. She had health problems and her second marriage fell apart, later dying in a car accident. Oddly enough, her last pornographic film in 1975, involved a couple who founded various churches in California, after being involved in various Billy Graham films.

THE SAVAGE SIDE

After discovering the porn star, Marilyn Chambers (1952 – 2009), Craven and Cunningham were approached by Hallmark, a small “exploitation” film company – basically focusing on sex and violence –, which dished up dirt and brutality for the double programme of a network of cinemas in Boston. It produced lower-quality, B-movies known as “grindhouse”, watched at drive-ins and in grimy projection rooms with sticky floors. Aside from its production line, Hallmark also imported Italian films known as “Giallo” films, a thriller and horror film sub-genre that had a strong influence on the new generation of film makers in the 1970s.

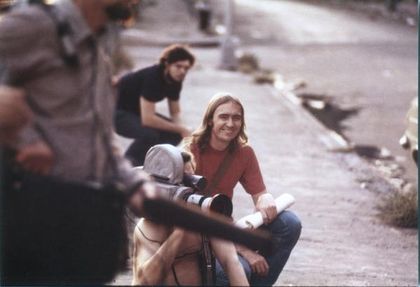

Craven filming his first terror movie, in 1972.

Craven filming his first terror movie, in 1972.Many of these companies had clear links to the mafia. In New York, where Craven was working, they were all based around Time Square – this provides the subject of an upcoming HBO TV series directed by the author of The Wire and starring James Franco–. In other cases, such as the Mitchell brothers in San Francisco, the rights were later obtained by the mafia through extortion – as in the case of “Behind the Green Door” (1972), the film which made Chambers famous, after being discovered by Craven–. All these cases ended up in a spiral of drugs and violence, which in the case of the Mitchel brothers, led to one brother murdering the other, and Chambers appearing one day dead at her home.

The mainstream success of these films was spectacular and it was partly the result of the comments they aroused, even on television – in shows such as the Johnny Carson show–. The expression “deep throat” was even used as the pseudonym given to the secret Watergate informant. This led to the coining of the terms “porno chic” and “the golden age of porn”. It has nothing to do with the horror films which Cunningham and Craven started to make, beginning with “The last house on the left” (1971), a story of love and violence, inspired by Bergman’s classic, “The Virgin Spring”. The difference is that the film by the son of a Swedish Lutheran pastor is written by a Christian, Ulla Jakobson, who ends the story with a miracle and a message of redemption.

As Zinoman says in his book on the generation that changed horror films in the 1970s, “there is no such miracle. In a godless world without redemption, it includes no struggle with faith. Instead the senseless evil inspires just more senseless evil, adding up to a nihilism that invites no happy endings”, but creating “moral ambiguity”. People who watch those films, looking for entertainment, discover that it is not easy to enjoy them without feeling guilty. In fact, they seem to be conceived to repel. According to Craven, “revenge was evidence that we all have a savage side and there was nothing to learn from that but that violence begets more violence”.

THE ULTIMATE APOLOGETICS

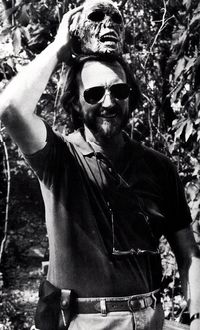

Family and religion where the sources of Craven's nightmares.

Family and religion where the sources of Craven's nightmares. If there are two recurrent themes in his career, they have got to be religion and family, which come together in films like “Deadly Blessings”(1981) or “The People Under the Stairs” (1991). The author of “A Nightmare on Elm Street” (1984) insisted that the key to his success was an understanding that what Americans fear the most is guilt, pain and shame, and that these things are the reason for their nightmares. These are the “disturbed dreams of a society”. If Freddy Krueger manages to upset us, twenty years after his murder at the hands of parents seeking revenge for his torturing and killing of their adolescent children, it is because the sins of the fathers are visited on the children, until the point of insomnia.

The most famous graduate of Wheaton College, along with Billy Graham, didn’t just have bad memories of his evangelical upbringing. In his last year of college, he was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome. He spent almost a year without being able to go to class and became very depressed. Speaking in an interview in 1997, he said that “People I didn’t know came to visit, to pray for my recovery. To me, their thoughts and prayers represented the best side of Christianity. I’ll never forget that side of Wheaton College. Never.”.

Before he died, Francis Schaeffer carried out an in-depth and self-critical review of his own work on apologetics. He called it The Great Evangelical Disaster. In these notes he considers his fundamentalist background in the quest for “sound doctrine”, which led to the creation of the Presbyterian denomination that sent him to Europe as a missionary. There, he came up against a faith crisis, which led him to open the L’Abri organization and to his writing about the God who is there and is not silent. In his meditations on John 17:20-23, he comes to the realization that it is through our love of others that the world will believe that Jesus is the Son of God. This is the “final apologetic”, the only one that can wake us from our nightmares.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o