Death for Ernest Hemingway was a release from the role that life seemed to have assigned to him.

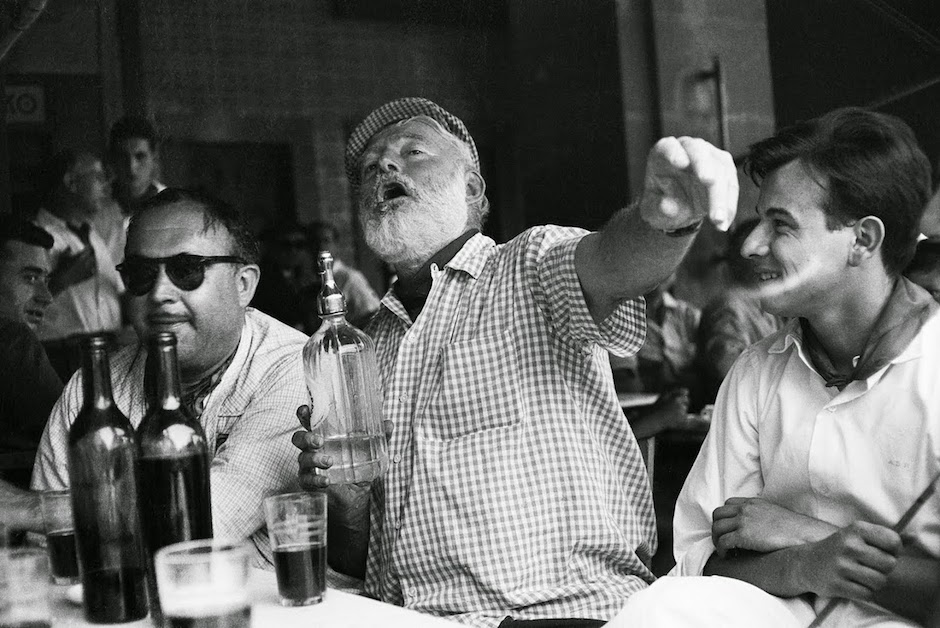

Behind Hemingway's virile exterior, there was someone profoundly self-destructive.

Behind Hemingway's virile exterior, there was someone profoundly self-destructive.

We all wear masks to hide the sides of us that we’d rather not show. Some people want to seem self-sufficient, others seek pity, others hide under a cloak of cold intellectualism, others under a certain look, while others still pretend indifference.

Some people take this as far as to develop such a high level of schizophrenia that they adopt different personalities depending on the place where, or the people with whom, they are.

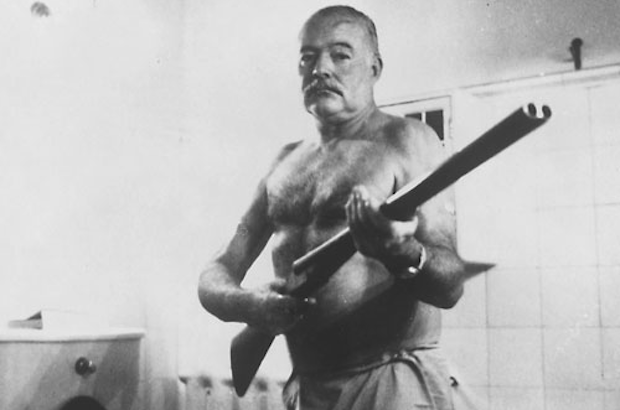

In a new biography of Ernest Hemingway, Venice in Autumn, Andrea di Robilant contrasts the myth of the author’s virility with the reality of his private life. In a previous biography, Mary Dearborn examined the sexual insecurity of the writer who would go on to shoot himself in the head at his home in Ketchum (Ohio) in 1961.

When he committed suicide, the general public could not believe that the brave winner of the Nobel literature prize would be capable of such a thing. The truth is that he thought about doing it all his life.

For him, death was a release from the role that life seemed to have assigned to him. Behind his virile exterior, hid someone profoundly self-destructive. The problem was that, often, his external persona got mixed up with whom he really was.

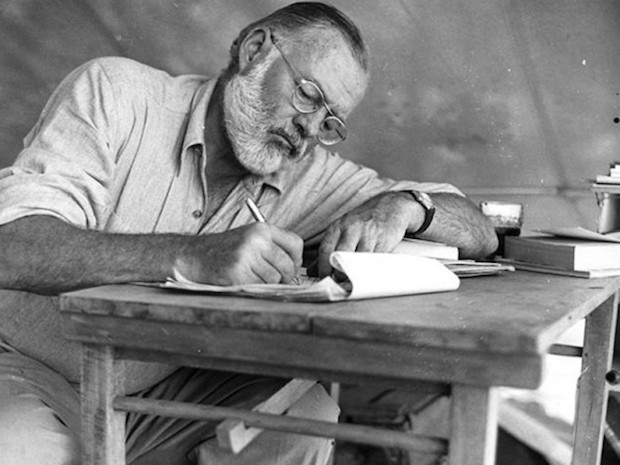

The first time I heard about Hemingway must have been from my teacher Juan Simarro – who taught me literature at the El Porvenir school in Madrid in the 1970s. I was so fascinated by his merger of literature and life that I borrowed all his books from the library.

It wasn’t long before I wrote an article about him, which was published in the first issue of a literary review called Aura. I don’t know if it’s the first thing that I ever published, but from then on I decided that I wanted to be a writer and journalist. I bought this book by Andrea di Robilant in London, just before the outbreak of the pandemic. It plays to various of my obsessions: Venice, Hemingway and finding love late in life.

Oak Park – the village, near Chicago, where Hemingway was born in 1899 – used to have almost as many churches as streets – all Protestant. The author grew up in a congregational, or independent, church. When he was little, the day began at home with reading the Bible and devotional notes.

Hemingway recalled that they would all kneel down on the carpet and his grandfather would pray to God, talking to him as if he were a friend. His grandfather had been an infantry commander in an African-American regiment, before entering ministry among young Christians in Chicago, where he worked with the famous evangelist Dwight L. Moody.

His grandfather's evangelical zeal became, however, a frustrating legalism with his father., Doctor Hemingway. The latter’s strict discipline probably revealed insecurity at not feeling adequate, neither as a husband, nor as a father.

When he used to hit his son for misbehaving, he would then make him kneel down and ask for God’s forgiveness. It was probably his way of asking for forgiveness too, in his own awareness of failure.

The year that Hemingway was born a new pastor started working at the family’s church. According to Kenneth Lynn’s monumental biography he embodied how church historian H. Richard Niebuhr would later describe liberal Protestantism, where “A God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a cross”.

So it was heavy on moralism, but light on the Gospel. It is therefore not surprising that one of Hemmingway’s characters referred to “Our nada who art in nada”, following the model of the prayer that Jesus taught us.

Hemmingway’s mother had not had the same puritanical upbringing as her husband, but she was so authoritarian that she made her son’s life very difficult, to the point of traumatizing him. Her name, Grace, could not have been more inappropriate.

Her domineering character was mixed in with frustrated expectations, having wanted to be an opera singer. She was very close to one of her pupils, with whom she built a house, where biographers suspect that they entered into a lesbian relationship.

When he started working for a newspaper in Kansas City, he stopped going to church, despite his mother’s recriminations. He started to write short stories and he enjoyed fishing, but he was obsessed with his virility – always questioned by his mother who dressed him as a girl, as if he were his sister Marcelline’s twin, while at the same time emasculating her own husband.

Hemingway tried to distance himself from her but when he ran into difficulties he kept on going back to her to ask for help, as he did with other maternal figures throughout his life.

During the First World War, he left for Italy as a volunteer with the Red Cross. There he was disappointed in love with a nurse in a hospital in Milan – inspiring characters in A Farewell to Arms –, when he was hospitalized with a shrapnel wound.

At home, he was welcomed back as a hero, but he exaggerated what happened to him so much that it became hard to distinguish between the truth and the lies. He soon left Oak Park, but Oak Park never left him…

People have said that it was a Protestantism without a cross that at times attracted Hemingway to Catholicism. Already, during the war in Italy he had met a priest who murmured some words by way of baptism as he lay injured.

What is true is that one summer day in 1920 he went into a Catholic church with his girlfriend at the time – Katy, the sister of his best friend from childhood, who would later marry the writer Dos Passos – to pray.

It was through the failure of his first marriage that Hemingway took an interest in Catholicism again. Although he had married Hadley Richardson and had his son baptized in an episcopal church in Paris, he didn’t otherwise set foot in a church until he met Pauline – who was to become his second wife.

She was working as a fashion journalist at the time and came from a Catholic family – her mother was so Catholic that she even had a chapel at home. He admired her so much that he soon felt that his heart was divided.

At Christmas 1925, while in Austria, he felt so confused by his sentimental dilemma that he thought of killing himself. He needed forgiveness for his feelings of guilt, but the crossless Christianity of Liberal Protestantism in which he had been educated could not give that to him.

Pauline encouraged him to find consolation in Catholic prayers. This is reflected when the main character in Fiesta goes into the Cathedral in Pamplona to pray but nothing happens. After visiting various Catholic churches in Paris, Hemingway finally gave up on religion altogether.

Hemingway believed that there was no hope in life; if God existed, he was indifferent; and the cosmos was like a machine that moved without rhyme or reason throughout eternity.

According to Lynn, when he set himself up in Cuba at Finca Vigía with his third wife – the journalist Martha Gellhorn, who lived with him during the Spanish Civil War – at the end of the 1940s, it was already “the beginning of the end”.

His whole world came crashing down on the day that his father shot himself in the head with a revolver that he kept in his desk. He started to have trouble sleeping, drank heavily and had recurring suicidal thoughts.

From 1957 until he finally killed himself in 1961, all his life and his work constituted a long debate about self-destruction. His behaviour increasingly resembled that of his father, although he believed that suicide was a cowardly act. He was particularly worried about the example that he would set for his children...

The first, John – who they called Bumby – was born from his first marriage but he was declared a bastard in order to allow Hemingway to marry Pauline in the Catholic Church. John nevertheless managed to have a family life, although one of his daughters – the actress Margaux Hemingway, who appeared in a number of films in the 1980s, including “Manhattan” by Woody Allen – is thought to have also committed suicide.

His sons with Pauline – Patrick and Gregory – lived trying to emulate their father’s example, among other things, going on safaris. Gregory died in the early 2000s in a women’s prison in Miami – having become transsexual. He had previously married his father’s secretary and lost his medical license due to alcoholism.

Hemingway was looking for that liberating love that we all wish for. The problem is that, like him, we aren’t brave enough to leave everything behind to pursue it because it would show us what we really are. But we don’t want to give up on our dreams.

We want to be free, but we are enslaved by so many things that our freedom is nothing but a mirage – like jumping off a cliff while trying to fly.

Jesus tells a story of a man who leaves his home in search of freedom (Luke 15:13). He wants the things that his father can give him, but not his father. He demands his inheritance and moves far away. His father is dead to him. However, one day, when he realizes that he is lost, he feels hunger and misses home (v. 17).

Our quest in life leads us towards that ultimate goal of a deep and meaningful relationship that will make us truly free. But the only one who can give meaning to our lives is He who has created us.

The atheist philosopher Sartre said: “That God does not exist, I cannot deny; that my whole being cries out for God, I cannot forget”. When we recognize that we are lost, we realize who we really are. And that is the first step to discovering the truth that will make us free and which Jesus taught us.

No one wants to recognize their guilt, but by wanting to live outside God’s rules, we are not failing to observe a series of impersonal dictates, but we are offending Him who loves us so much that He gave up what He most loved for us: His own Son.

That is the mystery of the cross, something as strange as that father who ran out onto the road, full of love and compassion, for the son that had broken his heart (Luke 15: 20). His open arms of unconditional acceptance offer us the freedom of never again having to pretend to be that which we are not.

That is how the Father accepts us in His family and at His party, when we present ourselves just as we are. And, to our surprise, He isn’t going to make us pay for everything we have done – as in a similar story told by Buddha – but Christ receives us in His mercy, giving us the life and the justice that we do not have, as an undeserved gift.

Our freedom has a price, but the good news is that Someone has already paid it for us.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o