Alice in Wonderland, which is turning 150, shows how children’s literature can raise some of the fundamental questions regarding our existence.

Alice in Wonderland turns 150.

Alice in Wonderland turns 150.

C.S. Lewis said that, “no book is really worth reading at the age of ten which is not equally, and often far more, worth reading at the age of fifty and beyond.” Having reached my own half-century, I have decided to go back to the books that have shaped my life. One of them is, of course, Alice, which is 150 years old this year.

Gil de Biedma says that nothing important happens to us after the age of 12, or at least nothing as important as anything that has gone before it. In many ways, the stories we heard as children made us face up to the fundamental questions regarding our existence. There are books which guide us, enlighten us, make us stronger, even if we don’t know how or why.

The stories that captivate us either in literature or cinema, always have some kind of dream-like quality to them, which makes it difficult to distinguish between dreams and reality. The world of Alice has a hypnotic power, playing on the secret recesses of the readers’ minds, allowing them to recognize a situation immediately, more by instinct than by their intelligence. Its scenes, rather than places, are emotional situations, which provoke a strange feeling of déjà-vu.

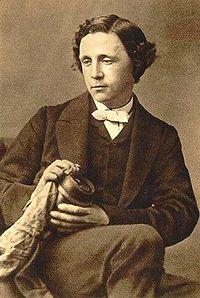

The book was written by a pastor who teached maths in Oxford: Charles Lutwidge Dodgson.

The book was written by a pastor who teached maths in Oxford: Charles Lutwidge Dodgson.A PASTOR’S STORY

On a summer afternoon in 1862, the pastor and mathematics professor at Trinity College, Oxford, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, accompanied his colleague, the reverend Duckworth, on a boat excursion on the Thames. They took with them the three daughters of the Dean of Christ Church, Lorina, Alice and Edith Liddell. The girls were bored and they asked to hear one of Dodgson’s weird and wonderful stories. He chose Alice, who had just celebrated her tenth birthday, as the main character of his story.

On listening to the story, pastor Duckworth asked him whether he was improvising. Dodgson said that he was making it up as he went along, more as something to say, rather than as a story. The original story was called “Alice’s adventures underground”. The little girl asked Dodgson to write it down and, the following Christmas, he presented it to her, copied out in his own handwriting and illustrated with his own drawings.

Three years later, he published it under the name of Lewis Carroll.

150 years ago, no one would have thought that this children’s story would achieve such success. In a way, the book has abandoned its author and has become independent of his original motives. Accordingly, his friendship with that little girl is now of little importance. His work has taken its own course. The revised text, published by MacMillan in 1865 – omitting a few personal references and adding other additional stories – together with the illustrations by John Tenniel, was entitled “Alice in Wonderland”. It was followed by another book, published in 1871 and entitled “Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There”.

A MAD TEA PARTY

The Cuban novelist, Cabrera Infante, once said that “that modest clergyman was almost singlehandedly responsible for inventing all the literature of our century”. Before Kafka had written a single line, Alice’s Queen of Hearts has already shouted out “No, no! Sentence first, verdict afterwards”. Parallels have often been drawn between Carroll’s work and “The Castle”, and “The Trial”, but where the world of the Jewish writer from Prague is oppressive and depressing, Alice’s world is tremendously revolutionary.

Alicia faces a topsy-turvy world.

Alicia faces a topsy-turvy world.In Carroll’s world, the absurd joins the tragic, as in life itself. However – as Alberto Manguel observes – the Alice books, rather than teach, mock the rituals of teaching. When she is examined by the Red and White Queens (“What’s the French for fiddle-de-dee?”), she replies with her nonsense “Fiddle-de-dee’s not English”, exasperating of the Red Queen (“Who ever said it was?”). In this way, she denounces the injustice of the sentence given by the King’s Messenger and the greed and despotism of the Queen (“The rule is: jam tomorrow and jam yesterday, but never jam today”).

Alice is confronted by the apparent folly of this world (talking to the Cheshire Cat, Alice says, “But I don’t want to go among mad people”. To which he replies, “Oh, you can’t help that […] we’re all mad here.”). As the story’s Spanish translator, Jaime Ojeda, observes, “the world of the soul is complex and unpredictable, and life forces us into circumstances that are no less complex and ungovernable”. That is how “everyone tries to find their own way in that labyrinthine dichotomy between one’s own self and life”. We thus go from the, amazement and fear of childhood, to the indignation that we feel towards stupidity and hypocrisy in adolescence, later highlighting, as adults, our own lies and failures.

SOMETHING TO BELIEVE IN

‘Let’s consider your age to begin with — how old are you?’

‘I’m seven and a half exactly.’

‘You needn’t say “exactly,”’ the Queen remarked: ‘I can believe it without that. Now I’ll give you something to believe. I’m just one hundred and one, five months and a day.’

‘I can’t believe that!’ said Alice.

‘Can’t you?’ the Queen said in a pitying tone. ‘Try again: draw a long breath, and shut your eyes.’

Alice laughed. ‘There’s no use trying,’ she said: ‘one can’t believe impossible things.’

‘I daresay you haven’t had much practice,’ said the Queen. ‘When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.’

Why can some people believe things that seem incredible to others? In the topsy-turvy world of the White Queen, faith is only a question of effort. On the other side of the mirror, we, like Alice, don’t see it quite so clearly. Faith is not the same thing as that which we would like to believe. Not seeing the difference is confusing reality with fantasy.

We can take a deep breath and close our eyes, but that isn’t faith. That is making ourselves believe something. By definition, something that you have to make an effort to believe, cannot be true because truth is self-evident. Christians believe extraordinary things: God, made man, walked on earth! However, they do not seem to have to make an effort to believe the impossible. Or are they more ingenuous than others? There is no doubt that some of them are, but credulity is not the same thing as faith.

THE ENIGMA OF FAITH

What is the enigma of faith? Why do some have it and not others? What is it that non-believers are not able to believe? Why are we able to believe it? Faith is based on the revelation of a truth that we can trust in. As the Spanish writer and theologian José Grau used to say, the question is not whether we believe in God or not, but in which God do we believe….

'When I use a word,' Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, 'it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.'

'The question is,' said Alice, 'whether you can make words mean so many different things.'

'The question is,' said Humpty Dumpty, 'which is to be master — that's all.'

If salvation depended on our capacity to believe, those with more imagination would be in with a head start. God is the one that gives us our assurance. It is not a question of making an effort. Otherwise, some of us would continue to think, like Alice, “one can’t believe impossible things”.

Faith is not a question of overcoming our own limitations, but of divine grace: “No one can come to me unless the Father who sent me draws them” (John 6:44). It is His voice that calls us. And it comes with His own authority.

That “effectual calling” that theology talks about, is the means by which God gives faith to men and women, not with the cruelty of a tyrant, but with the attraction of a lover. He does it by shedding light on His Word, by opening our understanding, touching our heart and freeing our will. It is therefore by faith that we embrace He whose word is truth. Even if it seems to good to be true…

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o