A child with SPD may have reactions which can be difficult to understand. Their body is automatically reacting to what is around them by being in a ‘fight’ or ‘flight’ mode, and this can be wrongly interpreted as bad behaviour.

Photo: Kelly Sikkoma (Unsplash, CC0)

Photo: Kelly Sikkoma (Unsplash, CC0)

What is a sensory processing disorder? Occupational Therapist Sheilagh Blyth explains…

Sensory processing (sometimes called sensory integration or SI) is a term that refers to the way the body receives and interprets messages from the senses. Humans have a multitude of senses that help them to gather information about the world around them and people process this information through the nervous system.

This tells an individual to react either with a motor or a behavioural response. For example, if a butterfly touches someone’s arm, the brain would receive a message that they could either feel or see that butterfly. How a person reacts to that sensation is dependent on how their body interprets sensations. They could brush the butterfly to one side, scream, wave their hands in the air or stand still in fright. Everyone’s reaction can be different.

Sensory integration usually occurs automatically and unconsciously without any effort. Someone with a difficulty may have a sensory processing disorder (SPD).

A child with SPD may have reactions which can be difficult to understand and explain. Their body is automatically reacting to what is around them by being in a ‘fight’ or ‘flight’ mode, and this can be wrongly interpreted as bad behaviour. Every day these children may feel overwhelmed, anxious, depressed, or appear aggressive.

Adults will often describe these children as being a fussy eater, emotional, stubborn, fearful, disruptive and uncooperative. These children may find it difficult to make friends, to sit still in class, or to work as part of a group. They may appear disorganised, or find certain clothing or clothing labels difficult to wear.

“Hi. My name is Harry and I have sensory processing difficulties. Some people call it SPD and others call it sensory integration difficulties. Seeing, hearing, touching and smelling tell us about the world around us. Movement, muscles senses, stretch and touch on our inside tells us about how our body is working and moving. Senses help us to know where we are, to know what to do and how to do it. For me those messages get in a muddle. This makes it tricky to pay attention, do my school work and even play with my friends. To me it can be annoying, but there are ways that I can make life easier and more fun.”

“I sometimes feel like my senses are crowding in on me and sound is too loud, touch is too scratchy, and lights are too bright. This makes me feel stressed. I just want to go somewhere quiet and not talk to anyone. My sister is called Anna. She has some sensory processing difficulties too. She misses what people say or her hands don’t tell her what they are touching or holding. Teachers can get cross because they think she is not listening when she is really trying. She has to look at her hands to know what they are doing. It helps us both to do warm-up exercises (like bouncing on a mini-trampoline) before we have to pay attention, do school work or even get dressed or go to sleep.”

Children usually present with three different types of responses to sensations: under-react, sensory seeking and over-react.

- Children who appear to under-react may appear withdrawn or be difficult to engage in an activity, they are watchful children.

- Sensory seekers need to activate their senses any way possible. This may be by wandering around the room (appearing to be uncertain and bored), swinging their feet or tapping their fingers, twirling their hair, biting their nails, tapping their pencil, or clicking their pen.

- Children who over-react may appear to be excessively emotional in response to events.

With (at least) eight different senses, three different ways of reacting, and every child’s response being unique, there is no one solution. Parents/carers or leaders can help by noticing if a child needs a quiet place to go to if there is too much noise. If a child gives firm bear hugs, this would suggest they like to feel deep muscle pressure. In that case a light touch or tap on this child’s shoulder to get in line at school or church could be an unpleasant sensation and could scare them into an overreaction. If a child is constantly fiddling, fiddle/fidget toys could help their concentration and focus.

Everybody’s sensory preferences are unique to them. No one else can tell you how you feel inside but your nonverbal communication will give other people clues. First of all, think about how you look and feel when you are happy and relaxed, or stressed or angry. Then think about how you recognise that in other people and your child/the child you’re working with. Practice reading those clues and thinking what the sensory qualities of that experience or environment are.

Understand – All of us have different sensory preferences and tolerance levels for sensory information. Sensory processing difficulties cause stress to children and to their families. They make the things that we do every day more challenging. They will impact on children’s learning styles. They are hard for other people to see and understand. Games that involve only visual demonstration (e.g. copying a sequence of movements) or only verbal instructions (e.g. ‘Simon Says’) will give you a starting point to identify their preferred or best learning strategies. Encourage children to be aware of what works best for them but also practice different strategies.

A busy environment can be overwhelming for children with sensory processing difficulties. Those who over-respond to sensory information are likely to have increasing difficulty as the session/class progresses, showing signs of tiredness or stress. Look out for children who demonstrate ‘fight’ or ‘flight’ responses to sound, visual, touch or even movement stimuli. This may include covering ears or hiding when a bell goes, or hitting out when brushed against by other children. They may avoid sports, especially when feet are away from the ground or where backwards and rotational movement is required. Under-responders appear switched off or do not appear to notice stimuli; they may not notice that clothes are twisted on their body, or food is on their face, or balance may be a challenge. These children are most often missed, as they are seen as well behaved, but they can also make the most progress when offered the right sensory input.

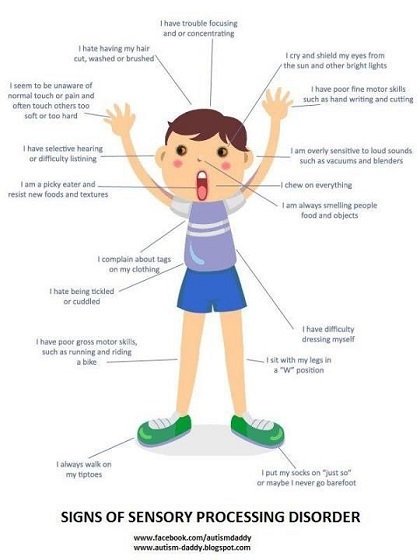

Source: autismdaddy.blogspot.com

Source: autismdaddy.blogspot.comTo help a child manage their sensory processing disorder both at home and in school or church look at the activity, the environment, and the individuals around them. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Would this activity result in the child under-reacting, seeking out sensations, or over reacting? Is it calming or stimulating? If so, can it be changed? Sometimes 10 minutes on a trampoline can calm one child but over-excite another.

- Is the environment set up to help that child? Or can they opt out if they need to? A time-out card shown discreetly to a leader can help a child to leave the activity, or be offered an opt-out option while maintaining their dignity. If a child becomes scared by too much noise, is it possible to create a den or quiet reading corner in the same room so that the child can still join in but from a “safe place”? Or maybe provide ear defenders for the same reasons?

- Perhaps a child who under-reacts may benefit from sitting on a wobble cushion or exercise ball to reawaken their senses. A wobble cushion or exercise ball can also help a child who is sensory seeking to concentrate by providing the movement they are seeking.

- Are you dressed appropriately? Some children find patterned clothing, dazzling jewellery or bright lipstick too visually stimulating. Others may find the smell of perfume or aftershave too overpowering causing them to be distracted from what they need to do or learn.

Change (light) – Is the lighting comfortable for everyone? Lights that flicker can cause stress, for example halogen lighting may be preferable to fluorescent strip lighting. Can you decrease or increase lighting levels according to the activity level required? Visual movement or seeing people move while you are trying to pay attention is particularly disruptive to some children. This may also be as simple as a tree blowing in the wind seen through the window, so ask the children to sit with their backs to the window. You may wish to think about layout so that children who struggle with visual attention do not have to deal with others walking in front of them. Visually busy walls (with lots of pictures or posters) can also be very visually distracting. You might want to think about keeping one wall blank.

Change (sound) – Sound absorbing materials or quiet spaces can help over-responders. Also consider background noise and where possible consider reducing it when focussed attention on instructions is required. Under-responders will benefit from cueing-in to the need to listen, for example by simply speaking their name before each instruction that you need them to follow. You might also want to mark transitions, for example, with the use of colour on a screen or gesture cues

Change (smell) – What does the room smell like? Are any of the children bothered by the smell? Look for scrunched-up noses! Then look to clear the air in the room where possible. Smells may be from an over ripe banana in the bin, glue sticks from the craft table, or markers from the white board. Children may be distracted in seeking out the smell or distracted by the smell being too strong for their senses.

Change (activity) – Remember to take some ‘activity breaks’ e.g. jumping on the spot, pushing down on a chair or table, star jumps, or handshakes to increase body awareness (proprioception). This helps focus attention and organise body movement. A good time for strategies like these are before sitting, writing or listening. Have ‘activity breaks’ regularly throughout the session, rather than as crisis management when a child “needs to move now!”

As a child becomes older, sensory diets can be a powerful behavioural tool in helping children to respond appropriately to their senses. A sensory diet is a personalised activity plan, designed to provide the sensory input they need to stay focused and organised throughout the day. The clue is in the word ‘diet’ rather than ‘crisis management’.

Done well, it should help with attention, concentration, sensory reactions and self-regulation. The concept is that the child rates their body in relation to a car engine, if it is going too fast then you need to look at the activity to see why. The aim is to have the engine running ‘just right’.

An Occupational Therapist (OT) with training in sensory processing disorders can help to devise a sensory diet and offer advice which needs to be specific to an individual child. The aim of any OT treatment is to help a child manage their own responses appropriately. For their carers, it is developing an understanding of how sensory processing disorder can affect a child, their functioning and their behaviour. This is a key part of an OT’s role; to ensure that all those working with the child understand their SPD and its impact. There are many adults who have sensory difficulties, however they have learnt to manage their responses. With help and understanding these children can learn how to play with friends and enjoy school, church etc.

Sheilagh Blyth is a children’s Occupational Therapist and founder of the ‘Enable Me Method’ which provides books, resources and courses to educators. Her article on Sensory Processing Disorder was originally published on ‘The Good Schools Guide’.

Article adapted from the original to fit this guide, along with additional content from Steff Shepherd, qualified Occupational Therapist and children’s worker, and with excerpts included from Sue Allen’s book, ‘Can I tell you about Sensory Processing Difficulties?’, highlighted above in Italics.

Mark Arnold, Director of Additional Needs Ministry at Urban Saints. Arnold blogs at The Additional Needs Blogfather. This article was re-published with permission.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o