Like many believers, Philip Roth feels bewildered at the relationship that the Bible establishes between plagues and God’s judgement. But can we apply this to epidemics nowadays?

Nemesis faces Dostoevsky's question of how a good and almighty God can allow the death of a child.

Nemesis faces Dostoevsky's question of how a good and almighty God can allow the death of a child.

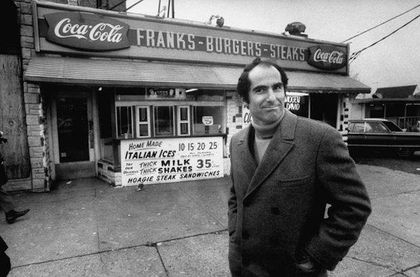

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, many people have been reminded of the last book by the North-American Jewish author Philip Roth (1933–2018), Nemesis.

In it he remembers the summer of the polio outbreak in 1944. The main character asks himself, as many of us are doing today: how can there be a good and almighty God that would permit this suffering?

Like many believers, he feels bewildered at the relationship that the Bible establishes between certain plagues and God’s judgement, but can we apply this to epidemics nowadays?

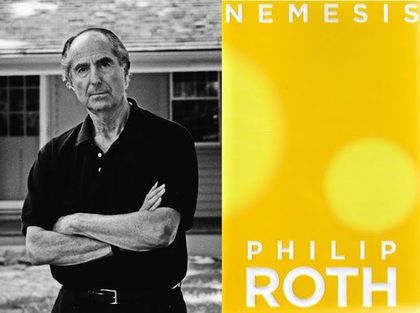

Realizing that life is coming to an end raises many questions in people. Before his death at the age of 85, Roth announced in an interview to the BBC that he was saying goodbye to literature.

He no longer appeared on TV or wrote anything, but he left us one last book that is “an artfully constructed suspense novel with a cunning twist towards the end”, as observed by the Nobel Prize winner J.M. Coetzee. It speaks of guilt and destiny, the mystery of God and the problem of evil.

Before he was accused of blasphemy, Roth was awarded an honorary doctorate by the conservative Jewish Theological Seminary of New York. His name came up every year as a candidate to the Nobel prize for literature, and he was awarded the Spanish Príncipe de Asturias prize in 2012 (he was not able to collect it in person as he was recovering from surgery). As he no longer wanted to write, he would reread his favourite novels.

Roth was born in 1933, to a Jewish family of Ukrainian origin. He published his first book, Goodbye, Columbus (1959) at the age of twenty-six, but he became famous when he moved to New York and published his fourth book, Portnoy’s complaint (1969), which tells the sexual obsessions of a neurotic Jewish boy and which was made into a film a couple of years later.

In all, he wrote more than thirty novels, studying the human soul – nine of them have the same main character, Nathan Zuckerman –all issuing the same word of warning: beware of goodness.

Until the 1990s, Roth worked as a university professor. He retired after marrying the British actress Claire Bloom – his first wife died in a car accident in 1968, shortly after they separated.

Over the course of that decade he tried, like so many others, to write “the great American novel”, in a series of books covering the period from the Great Depression until the present, by way of the Second World War, McCarthyism and the terrorism of the 1960s.

In his latest book, Roth returns to the coty of New Jersey where he was born, Newark.

In his latest book, Roth returns to the coty of New Jersey where he was born, Newark.

THE INVISIBLE THREAT

After exploring the theme of ageing in The Dying Animal, Roth faces up to death in the place where his own life started: Newark. In his last book, Nemesis, he goes back to the city in New Jersey where he was born to remember the stifling summer of 1944 when children like him died in the polio epidemic.

Bucky Cantor is a Jewish physical education teacher, who has not been allowed to go to war because of his poor eyesight. He is an orphan, having lost his mother at birth twenty-three years earlier.

“[B]ecause of the loving care that he received from his grandparents, it had always seemed to him that losing his mother at birth was something that was meant to happen to him and that his grandparents’ raising him was a natural consequence of her death. So too was his father’s being a gambler and a thief something that was meant to happen and that couldn’t have been otherwise. But now that he was no longer a child he was capable of understanding that why things couldn’t be otherwise was because of God. If not for God, if not for the nature of God, they would be otherwise”. (pp. 124–125).

That summer sees the outbreak of the polio epidemic, with devastating effects among his pupils. The death of so many of them makes him feel a mixture of stupor and rage.

“His anger provoked … not against whatever cause, however unlikely, people, in their fear and confusion, might advance to explain the epidemic, not even against the polio virus, but against the source, the creator – against God, who made the virus.” (p. 127).

Polio is a contagious virus that appears in early childhood and causes fever, headaches, a sore throat, nausea, rigidity in the neck and joint pain. By attacking the nervous system, it can cause paralysis and even death.

Good hygiene can reduce the risk, but it can be deathly. The development of a vaccine in the middle of the last century led to its eradication, but in 1944 there were 19,000 cases in the United States. The most famous patient was President Roosevelt.

These epidemics produce a psychopathology in affected groups which, as in the AIDS outbreak, do not understand how it is transmitted. Many people suffer from panic attacks and feelings of desperation.

In his Journal of a Plague Year, Daniel Defoe imagined the experience of a survivor of the bubonic plague that laid London low in 1665. Albert Camus took inspiration from this book during the Second World War to write The Plague, which, in an interview in 2008, Roth said he was reading.

He thus comes up against an invisible, inscrutable and deadly force, which some have related to the post 9/11 syndrome, but which the author repeatedly denied.

THE PROBLEM OF GUILT

The surprising thing about Roth’s book, is that it addresses the problem of guilt. First, because the main character, Bucky, is ashamed that he did not go to war, while his friends are on the front.

He tries to pay for it by providing children with a healthy activity and giving them all his care and attention. This makes the children love him. Bucky is a sensible and honest person, with a strong sense of duty and honour.

In the midst of the general panic, he remains calm, creating stability, while internally is railing against the cruelty of a God who kills innocent children.

Bucky has a girlfriend called Marcia, the daughter of a doctor that he admires. In the summer she works in a summer camp in the mountains of Pennsylvania. She pressures him to leave the infected city to join her in her seclusion.

He refuses, believing that extraordinary situations call for extraordinary sacrifices. One day, however, his principles inexplicably give way. He abandons the children to save himself, thus placing a weight on his conscience: “How could he have done what he’d just done?”

Roth's work not only faces the problem of pain, but also guilt.

Roth's work not only faces the problem of pain, but also guilt.I won’t reveal the main reason for his guilt, so as not to spoil the ending. However, what I can say is that he comes face to face with the problem of the cosmic justice of the “God who created the virus”, and of the responsibility for the “human plague”.

As a good Jew, he cannot conceive of an impotent God. Accordingly, “[e]ither it’s terrible God who is accountable”, spending “too much time killing children”, or “it’s terrible Bucky Cantor who is accountable”.

Faced with this dilemma, Marcia declares that “in fact, accountability belongs to neither”. She thinks that his “attitude towards God – it’s juvenile, it’s just plain silly”. She believes that he has “no idea of what God is! , because No one does or can!”.

This is a very typical belief in modern Judaism, which tends to be pretty agnostic. Coetzee interprets this attitude as “God is not accountable because God is above accountability, above mere human reckoning”. Marcia thus “echoes the God of the book of Job, and the scorn expressed there for the puniness of the human intellect”.

JUST PUNISHMENT?

The title Nemesis, however, poses this question about cosmic justice in Greek terms, referring – as Coetzee points out – to Sophocles’ Oedipus. Nemesis in Greek means righteous anger.

In Latin it is translated by the word indignatio, from which we get “indignation”, referring to unjust acts and just feelings of anger in the face of such actions. The tale of Oedipus centres around the question: how does the logic of justice work when universal forces intersect the trajectories of individual human lives?

The idea of fair punishment permeates Greek tragedy like a feared force that governs human affairs, behaving in an underhand, evil, cruel, selfish and relentless way.

In the face of this mentality, which was adopted by Judaism during Jesus’ time, the Gospel of John presents us with a man who is blind from birth, of whom the disciples ask Jesus: “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” (9:2).

Jesus’ answer is entirely unexpected: “Neither this man nor his parents sinned, but that the works of God should be revealed in him” (9:3).

American Jewish writer Philip Roth died at the age of 85.

American Jewish writer Philip Roth died at the age of 85.There are no easy answers when it comes to human suffering. The Gospel does not teach us that Christians have a right to health, nor that illness is a necessary consequence of personal sin.

Although the Bible does link some disasters and epidemics to divine retribution on a particular individual or nation, there is no basis to claim that we suffer divine punishments when our sins are particularly bad, or when we persist in committing a given sin.

The Bible says this of certain people or nations in specific moments in time, but we can’t apply it to everything we go through in our day-to-day lives, as if we had a divine explanation for specific instances of suffering.

Many believers suffer from what the Spanish theologian Pablo Martinez calls “cudgel theology”, in other words, the idea that God is waiting for us to fall, in order to mete out the punishment we deserve.

If we stop to think, we will realize that experience teaches us the opposite: God does not treat us as we deserve. Full of grace and mercy, he is patient with all of us.

THE ORIGIN OF EVIL

The origin of evil has been referred to as the “Achilles heel” of Christianity, being the subject of much speculation and criticism. John Stuart Mill observed that

“[i]f God desires there to be evil in the world, then He is not good. If He does not desire there to be evil, yet evil exists, then He is not omnipotent. Thus, if evil exists God is either not loving or not all-powerful”.

In the face of the many philosophical theories that believers advance on the subject of free will, theology has made various attempts to develop theodicies, or rational justifications for how God can be just and, nevertheless, allow evil in the world.

Many have thus converted evil into good. They claim, on the basis of Romans 8:28, that evil is temporary, but goodness is eternal. Does Paul mean that “all things are good”? No, but that “all things work together for good to those who love God”.

We cannot deny the reality of evil. That is what Isaiah is warning against when he says: “Woe to those who call evil good, and good evil; who put darkness for light, and light for darkness; who put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter!” (5:20).

The most common theodicy, however, blames all evils on Satan. This is ultimately a form of dualism, presenting the existence of two forces that are equally powerful and eternal.

This is not what the Bible teaches. This approach seeks to remove all responsibility from God, making evil eternally independent from him. As Bucky says, we cannot maintain God’s goodness at a cost to his omnipotence.

Dualism limits God’s eternal power. If Satan were equal in power to God, there would be no way of overcoming him. There would be no guarantee, or possibility of redemption.

A third type of theodicy speculates on the temporary need for evil in order to appreciate goodness. We are told that one needs to be ill, in order to appreciate health.

According to that logic, God would have had to experience evil in order to love goodness. Evil is the denial of goodness. It is the absence of it or its deprivation. In that sense, it is true that it depends on goodness for its definition. It does not exist on its own.

Roth recalls the stifling summer, when children like him died of a polio epidemic in 1944.

Roth recalls the stifling summer, when children like him died of a polio epidemic in 1944.

THE ANSWER OF THE CROSS

Neither believers nor non-believers have the solution to the problem of evil. In space and time, the Bible locates it in the Fall described in Genesis 3, but it does not give us the origin of evil.

If God saw that creation was good, where does evil come in? The difference is that believers know where good comes from. Non-believers do not know where either force originates.

The tragedy that Nemesis describes is a problem for us all. It is not a reason to lose faith, because the believer does not understand it either.

The Bible teaches us that we come from a broken world. We are born in sin (Psalm 51:5; Romans 5:12–21) and that is why we die. Christianity does not give us the answer for why we have to suffer pain, but it gives us hope in the midst of suffering.

God experienced the full depth of pain through Jesus Christ. For many, speaking of God’s suffering goes against the doctrine of divine impassivity, but, as Luther observed, the cross shows us God crucified.

There is no greater agony than that. “My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46; Mark 15:36). He felt not only physical suffering, but a cosmic abandonment.

Christianity is the only faith to believe in a God who has fully felt our humanity. He experienced despair, rejection, loneliness, want, bereavement, torture, prison and death.

The suffering of the cross exceeds any suffering we have known, so that God, taking our pain and misery, can be God with us, Emmanuel. Because he was abandoned so that we would no longer be abandoned.

Why does God allow so much pain and suffering? I don’t have the answer to that, but when I look at Jesus’ cross I do know that He is not indifferent. “For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have everlasting life.” (John 3:16).

Our suffering is not in vain. Beyond the cross lies an empty tomb. Resurrection brings a new heaven and a new earth in which “God will wipe away every tear” and “there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying. There shall be no more pain” (Revelation 21:4).

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o