In the winner of the last Golden Globes, “1917”, Sam Mendes draws on his grandfather’s experience of the First World War.

0 “1917” is the Golden Globes winner. / IMBD

0 “1917” is the Golden Globes winner. / IMBD

In the winner of the last Golden Globes, “1917”, Sam Mendes draws on his grandfather’s experience of the First World War.

This “war to end all wars” resulted in slaughter on a scale that had never been seen before, and has never been seen again. More than ten million people died in the conflict.

In one single day, 57,470 British soldiers fell at the battle of the Somme; 19,240 never got back up. More French soldiers died in twenty-four hours than the Americans that died in the whole Asia–Pacific War or in Vietnam, these being the wars that took the greatest toll on the United States.

The figures for all of the countries that participated are horrifying. It is not for nothing that they call it the Great War.

The war not only cut short a whole generation, but it shattered the dreams of peace and progress that had been born out of the optimism at the start of the century. These battles destroyed the hopes and dreams of a world that was nearing its end, waking it up to a crueller reality.

A violent death is always atrocious, but to die young in a war is heart-breaking: healthy bodies burnt alive, dismembered by the explosion of a bomb or the impacts of machine gun bullets…

There are lots of ways of dying at war. Many people died in deadly chemical discharges, in gas attacks, or riddled with bullets; but others died of hunger or from disease. Civilians were looted, detained on arbitrary charges, their rights violated.

So many people lost loved ones, saw their cities devastated and their fields destroyed, for the sake of a civilization that art was incapable of redeeming. The cinema captured the horror of a conflict, which, far from exalting great ideals, showcased the poverty of the human soul.

LIFE IN THE TRENCHES

The First World War was a trench war. Just a few metres away from each other, the two sides occupied positions for years, gaining a bit of enemy ground, to then slip back again.

Meanwhile, the soldiers built tunnels to plant explosives, or went over the top of the trenches in offensives that killed most, falling like flies under the booming artillery or gunfire, bullets whistling all around them. But most of the time, they just waited and that became a whole routine.

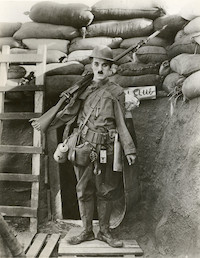

One of the most famous images of Charlie Chaplin shows him in a trench, dressed like a soldier, with a rifle on his shoulder. This photograph appeared on posters that hung on many walls in the 1970s. “Shoulder arms” (1918) was actually one of his most successful films.

It premiered three weeks before the armistice. His best gags took place in trenches. Life dodging explosions and gunshots seems to eradicate fear, stress, and even heroism. Monotonous boredom, marked by repetition and tedium was the routine on the front, creating its own daily mechanism.

The First World War was a trench war.

The First World War was a trench war.Trench warfare is a metaphor for life itself. We spend most of the time waiting. We sometimes see progress, followed by steps backwards. One thing can blow our lives to smithereens. In the feared Belgian front at Ypres, a tunnel was dug with explosives that created a huge crater and killed 9,922 British and Canadian soldiers.

As I walked through the cemetery where the victims are buried, I noticed that there are 3,500 unidentified soldiers. On their tombstones it says “Known unto God”.

ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT

The first film I saw about the First World War was “All Quiet on the Western Front” (1930). The Internet tells me that they showed it on Spanish television in 1978. As TV was still in black and white back then, I didn’t notice how old it was.

It made such a strong impression on me that ever since I was a teenager I have had a strong aversion to war. I wanted to be a conscientious objector, even before there was an alternative to the military service – which, for family reasons, I never did. I am not a strict pacifist, but I never felt that I could join the army.

At that time, I would read anything that I could find in the library. This included All quiet on the Western Front. It was written by a German author under the pseudonym Erich Maria Remarque. Hitler said that he was a Jew and that his real name was Kramer.

This was not true. He was a war veteran called Remark. He gathered all his memories of the war in a brutal realist novel, written with relentless sincerity and compassion.

The film was directed by Lewis Milestone, who won an Oscar for it. I find the lyricism of some of its dialogues overpowering: “our bodies are earth, and our thoughts are clay, and we sleep and eat with death!”. It never becomes sentimental, however.

The camera scrutinizes the battlefield with no musical accompaniment. A widow’s gaze gets lost as she watches her son play soldiers at the door of the house; shockingly, a pair of amputated hands, hold on to barbed wire fencing.

FAREWELL TO ARMS

“A Farewell to Arms” was the first of Hemingway’s novels to be adapted to the cinema. It is a love story that moved me the very first time that I read it as a teenager. It holds the key to Hemingway’s disenchantment, both with his sentimental relationships and with his faith.

He was an ambulance driver in the First World War. He got to Milan just as they blew up a huge munitions factory and had to get started straightaway helping to find bodies.

One of the most famous images of Charlie Chaplin shows him in a trench, dressed like a soldier.

One of the most famous images of Charlie Chaplin shows him in a trench, dressed like a soldier.It was at this point that he became friends with a young priest in Florence, called Giuseppe Bianchi. He is presented to us at the beginning of the book, when a group of solider are giving him a hard time and a commander says: “all thinking men are atheists”.

In the summer of 1918, Hemingway was injured by the explosion of a shell. He was taken to hospital in Milan, where he was looked after by a nurse who had been a librarian in Washington. Her name was Agnes von Kurowsky.

“Ag” was not only older than him but she was also engaged to a doctor in New York. Hemingway fell so deeply in love with her that he soon asked her to marry him. She didn’t take him very seriously. She would call him “boy”.

One day Ag told him that she had written to her fiancé to break off the engagement. Hemingway was so convinced that he was going to marry her that she became Catherine Barkley, the great love of lieutenant Henry in “A Farewell to Arms” – played by Helen Hayes and Gary Cooper in the film by Frank Borzage in 1932.

It was in an American hospital that Ernie saw Ag for the last time. On returning home, she would write to him from Venice, where they had transferred her. In a letter written in 1919, she confessed that she was with another man, telling him that she wasn’t as perfect as he thought.

Hemingway’s sister said that his disappointment was so great that he was taken ill. He couldn’t think about anything else. He would say that memories of the war stopped him from sleeping.

He was afraid that he was losing his mind and started to fantasize about committing suicide, considering self-destruction, however, to be cowardly. His story is told in a film by Richard Attenborough, “In Love and War” (1996), starring Chris O’Donnell and Sandra Bullock.

In 1957, Charles Vidor – who shouldn’t be confused with King Vidor, the director of the best silent film about the First World War, “The Big Parade” (1925) – made a mediocre colour version of Hemmingway’s book.

It was going to be directed by John Huston, but he was at odds with the producer Slznick. The main actors were Rock Hudson and Jennifer Jones. The mystic perspective of Borzage’s film provides a better reflection of the relationship that is found in the book, between love and dependence on God. It is presented as a journey between heaven and hell.

THE LOVE THAT CONQUERS DEATH

When faced with death, humans always seek security, comfort and happiness in love or in religion. When a person experiences true love, they are ready to sacrifice themselves for the person that they love – or maybe worship.

Catherine says to Henry: “You’re my religion. You’re all I’ve got”. Hemingway made the same observation, realising that “I forgot all about religion and everything else because I had Ag to worship”.

Hemingway must have had a lot to talk about with the priest that he met on the front lines. There are many stories about the close relationships that priests developed with soldiers in the war.

Their closeness to death made the soldiers express their fears and regrets in a way that they would never have done in peacetime. In the novel, the chaplain says to Henry:

"You understand but you do not love God.”

“No.”

“You do not love Him at all?” he asked.

“I’m afraid of Him in the night sometimes.”

“You should love Him.”

“I don’t love much.”

….

“You will. I know you will. Then you will be happy.”

“I’m happy. I’ve always been happy.”

“It is another thing, you cannot know about it unless you have it.”

“In Love and War” (1996), starring Chris O’Donnell and Sandra Bullock.

“In Love and War” (1996), starring Chris O’Donnell and Sandra Bullock. In life there are certain things that we think we know but that we don’t really understand until we have experienced them. This is what happens in love. We always hear about it, but we wonder whether it really exists. It does not touch a chord in us until we have experienced it.

This is the logic presented in the first epistle of John. In order to love God, we need to have felt love first (1 John 4:19). That is why it is useless to talk to some people about faith. People want proof, but if we are not prepared to put it into practice, what is the point of talking about it?

GOD’S JUDGEMENT?

Hemingway’s disillusionment lasted a lifetime, along with his image of God, not as someone to love, but as a punishing judge. This is what Spanish psychologist Pablo Martínez calls “garrotte theology”.

We imagine God as brandishing a stick, waiting for us to fail. That is why Henry is afraid of him in the night.

Many people live lives dominated by fear. They are afraid that something disastrous will happen to them as a judgement for their sins, as retribution for their slow spiritual progress towards a saintly life.

If, when something bad does happen to us, we think that it is a punishment from God, it means that we have not yet discovered the depth of His love.

That is how Henry prays when Catherine is about to die after a caesarean. It is a problem of the heart. Although we may think that we have a heart of gold, the Bible teaches us that we are not naturally capacitated to love.

If we are able to love, it is because God is in us (Galatians 5:22–23). Otherwise, resentment and mistrust dominate us. In our natural state, we are incapable of love.

Natural man rejects the idea of judgement, as a primitive superstition, but finds consolation in thinking that if some kind of god does exist, he will be a god of love. How does he know that? That is the problem!

Many people say that they are not afraid of dying, but they do not know what will happen. The fear of death is a fear of the unknown, which enslaves humanity through the work of evil (Hebrews 2:15).

Trying to get rid of it by saying that we are repressed by feelings from our education, is like whistling in the dark to try to convince ourselves that we are not afraid.

“The dread of something after death”, Shakespeare says in Hamlet, comes from “the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveller returns”. But one person did return and that is the key message of the gospel.

The Prince of Peace has vanquished death in a “war to end all wars”. His resurrection points to the day when “there will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain” (Revelation 21:4). Now we “hear of wars and rumours of wars … but the end is still to come” (Matthew 24:6). One day, light will chase the darkness away.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o