Many crime fictions happen in the past, as if by looking back, we find a way of diagnosing the traumas of the present.

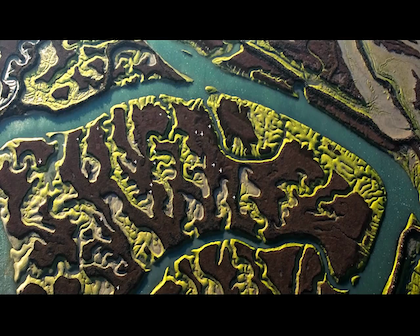

A scene of Marshland, one of the best Spanish films in the last two decades.

A scene of Marshland, one of the best Spanish films in the last two decades.

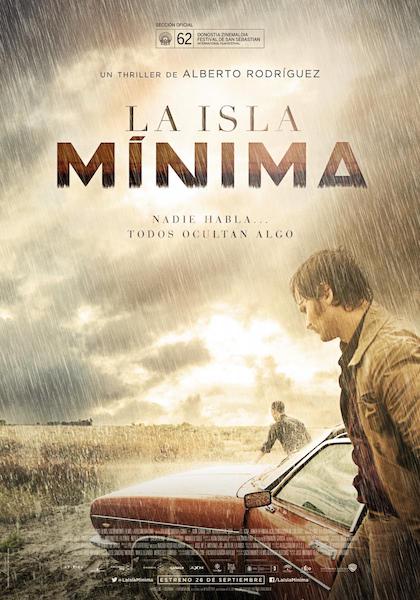

To celebrate the 500th issue of the Spanish cinema review Dirigido por, Spanish critics chose “La isla mínima” (in English, “Marshland”, 2014) as the best Spanish film of this century. Its history shows us that “the past lives in the present. Any little thing, however insignificant and banal, can make it rise up again to make us into who we used to be”, as Javier Cercas says in his book El vientre de la ballena. Yesterday’s shadow is a long one. We thought that we could move on and close the door on our recent past, but the muddy, swampy present, shows us that there are too many open wounds.

People say that crime fiction becomes popular in times of crisis. It is indeed true that some of the books, films and television series that are currently popular would be put in the crime genre. It is interesting that many of them happen in the past; as if by looking back, we find a way of diagnosing the traumas of the present. And there is no better way of casting light on the darkest corners of our society than in thriller mode.

Fascinating from opening credits, the intense story of “Marshland”, takes us back to the beginning of the 1980s. This dazzling film introduces us to two Madrid police officers who go to the area of the Marismas del Guadalquivir in Andalusia, to try to make sense of the mysterious disappearances of several girls, seemingly vanished into thin air. The menacing atmosphere of the Spanish period of transition from dicatorship to democracy creates an oppressive mood in this jumpy drama, where the intrigue follows a millimetric precision.

WHERE IS ALL THIS COMING FROM?

The characters, scenario and period might suggest that the film is inspired by the series “True Detective” but the American HBO production came after the film by Alberto Rodríguez, who is from Seville. He had already shown his metal in this cinema genre with “Grupo 7” (2012), a powerful story of police corruption in the years running up to the inauguration of Expo 92, when the centre of Seville was overrun by drug trafficking.

The thriller describes the struggles of rural Spain.

The thriller describes the struggles of rural Spain. It was when he was visiting an exhibition of the photographer Atín Aya that Rodríguez started that the idea came to him of a western film in and around the small islands in which people live in isolation across the thousands of hectares on which rice was cultivated until the civil war. Inspired by documentaries by the Bartolomé brothers, such as “No se os puede dejar solos” (1981) and “Atado y bien atado” (1983), and by a somewhat forgotten Spanish film, “El cebo” (1958) by Ladislao Vajda, we face the ghosts of a democratic transition in Spain that our society has not yet properly digested.

Similar to the current situation, the beginning of the eighties was a period of unemployment triggered by a rampant economic crisis, when Spain was trying to constitute itself as a country but was also discussing laws on subjects such as abortion. There is truly nothing new under the sun! Behind our supposed modernity, we continue arguing about the hidden corners of our collective memory in a country that continues bogged down in corruption. Everyone has a skeleton in the cupboard that has a way of pushing its way out.

BIRD’S-EYE VIEW

The film opens with panoramic views from the sky of the marshlands around the Guadalquivir River, pre-figuring a police investigation that gets lost in space and time. On the ground, the horizon stretches out forever, but the view from above forces us to take a step back from events whose injustice cries out to the heavens.

The view from the sky contrasts witht the vision on the ground.

The view from the sky contrasts witht the vision on the ground. As in the Korean film “Memories of Murder” (2003), or “Zodiac” by David Fincher (2007), “Marshland” reflects our current chaos in a nostalgic crime story. The spectator sees everything through the eyes of Juan (Javier Gutiérrez) and Pedro (Raúl Arévalo), as strangers in a foreign land. There, where the world seems to come to an end, they discover the heart of darkness.

This impossible mission includes trying to convince both the authorities and the girls’ families that they did not just leave in search of hotel work by the Mediterranean, chasing the winds of possibility of those new years. Drug trafficking, workmen’s petty vengeances and the resistance of caciques come up against the persistence of an agent, Pedro, who wants to get to the bottom of this dark, murky and impenetrable affair.

In Spain, something of that dark reality, which doesn’t appear in the official histories, came to light in sensationalist weekly TV shows such as “El Caso” and “Interviú”, which were very popular at the time. That is the daring journalism embodied by Martínez (Manolo Solo), a photographer who suffered repression under Franco and who becomes the third main character of the film upon discovering what lies beneath these turbid waters.

A CRY TO HEAVEN

Rodríguez says that the aerial shots that structure the film have a metaphorical explanation. Juan the police officer feels like someone is waiting for him, possibly as a result of being a practicing Catholic. The view from the sky contrasts with the reality below, his fear of hell, the devil and all the dead people in his life. In the film “Caimán”, Javier Estrada observes that his films often contain religious symbols. In this case, we also find political connotations, such as the crucifix in the hotel alongside Franco, Hitler and Salazar.

It is said that the noir genre revives in times of crisis.

It is said that the noir genre revives in times of crisis.The director says that his research drew a lot from a book by Alfonso Grosso, a writer of the Transition period, who won one of the main Spanish literary prizes for his story about a real crime in Andalusia, “Los invitados” (The Guests). Coincidentally, when I was a teenager at the end of the 1960s, he was the first person that I interviewed on the phone. The book was “Por el rio abajo” (Downstream), which tells of a trip that Grosso went on with the Communist Armando López Salinas in 1960. It contains a description of the crucifix hanging in the B&B in the film.

This trip into the heartlands of Spain awakens the darkness that corrupts all humans. People believe that the problem of corruption in this country concerns a small group of bankers and politicians, who need to be punished. The reality is that this is simply a manifestation of the disease that the Bible calls sin. We are happy to seek justice, in general terms, but when it reveals the evil in our own heart, we fall over ourselves making excuses.

Most people believe themselves to be essentially good. They try to do their best, and do not think that they hurt anyone. We all seem to do the right thing – especially when other people are looking our way – but what is the reality of our life in the eyes of God? We want to be happy, but we do not realise that happiness is the consequence of something, rather than its cause. Jesus tells us that the happiness appears when we “hunger and thirst for righteousness” (Matthew 5:6).

The eighties in Spain were a time of unemployment, as shown in the film.

The eighties in Spain were a time of unemployment, as shown in the film.HUNGER AND THIRST FOR RIGHTEOUSNESS

If our need for justice were as great and as overwhelming as the feelings produced by physical hunger and thirst, we would not consider the evil in us as a small thing. We comfort ourselves in saying that everyone has flaws, and that nobody is perfect. It is in the light of God’s justice that our best deeds are nothing but poor rags (Isaiah 64:6). What about our bad deeds, then?

Our justice is relative, so much so that God says: “There is no one righteous, not even one… There is no one who does good, not even one” (Romans 3:10–12). The Supreme Judge is not interested in our empty words. His understanding of justice goes much deeper. Our concept is that of the Pharisees: an external justice, based on our trust in ourselves. That is why it leads to pride and hypocrisy.

In Jesus’ beatitudes, we once again find the marvellous good news of grace. “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled”. It is a gift from God. We cannot find it elsewhere than in Him. It is through faith in Jesus Christ that this righteousness is given to all who believe (Romans 3:22), and that we are “justified freely by his grace” (v. 24). He promises that if we come to Him, through Jesus Christ, we will never hunger again.

At the heart of the gospel, there is a glorious exchange. We place our sins on the shoulders of Jesus on the cross, and He offers us perfect justice (2 Corinthians 5:21). Being filled with his righteousness, “we are perfect” – as Philippians 3 says – but that does not mean that we have made it. We will discover that we continue to experience hunger and thirst for this righteousness.

The film shows the persistence of a police officer facing a corrupt system.

The film shows the persistence of a police officer facing a corrupt system.The more we grow in his righteousness, the more we will realise which ideas and attitudes are not in line with God’s governance. He sees us, however, through Christ’s righteousness. And one days we will see ourselves as He sees us, perfect and unblemished.

On that day his holiness will fill the Earth, as the waters cover the sea. We will be truly clean, like Him. And our own body will be transformed as justice triumphs through the resurrection of Christ. God has the last word. All things are made new again and the past will cast no more shadows.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o