Ferry, like so many, does not seriously consider Christianity’s truth claims; he simply does not believe.

“To honestly and sympathetically deal with the best case that any form of unbelief can make and then show the desperate need that still remains and how it can only be met by the true God and His redeeming son - this is the excellent way.” - Ralph Winter

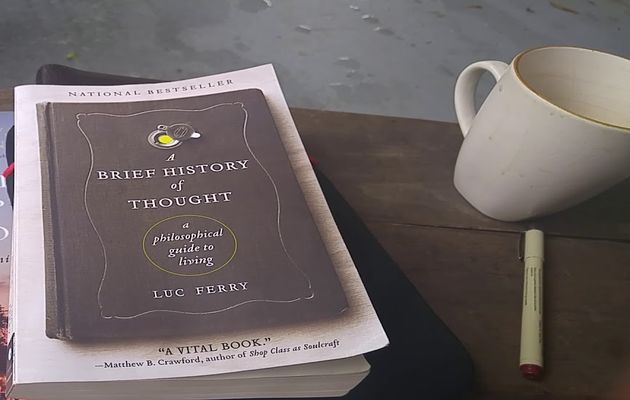

To read Luc Ferry’s A Brief History of Thought is to pursue Winter’s “excellent way”. It is to arrive at the end of Ferry’s excellent survey of over three millennia of philosophy feeling great respect for the author in his honest wrestling with the great questions, but simultaneously having become even more convinced of the “desperate need that still remains and how it can only be met by the true God and His redeeming son ...”.

Ferry’s book ends up bolstering Christian faith by demonstrating that the alternatives, including his own, don’t work.

Ferry’s starting point is the challenge to religion and philosophy of the peril of inevitable death. He rejects religion in favour of the great philosophies which can “be defined as doctrines of salvation (without the help of a God)”.

However, in his advocacy of a “transcendent humanism” that rejects any appeal to a transcendent God, Ferry makes two related errors.

First, he pits faith against reason: philosophy in contrast to theology, incites us “to turn aside from faith, to exercise reason ...”. To Ferry, faith is an anti-rational way of knowing. Yet this is not a definition of “faith” that any competent Christian theologian would accept.

The second and related error is revealed in Ferry’s statement that philosophy “unlike the great religions, promises to help us to ‘save’ ourselves, to conquer our fears, not through an Other, a God, but through our own strength and the use of our reason”.

This is a remarkable (and representative) expression of faith in human strength and unaided reason, and unmasks the unstated assumption that philosophy does not depend on faith commitments.

It would be a good critical reading task for the young Christian to familiarise themself with Ferry’s account and observe his unstated beliefs woven through the book.

Of course, it risks a cheap shot to ask how that particular project of dependence on “our own strength and the use of our reason” is turning out. The history of the 20th century has a great deal to say on the matter.

There is so much that is good in Ferry’s journey from early Greek philosophy to his concluding challenge of doing philosophy post-Nietzsche, and there are necessary corrections to common misunderstandings.

Nowhere is this more true than in his detailed and sympathetic outline of Nietzsche’s thought, which alone is worth the price of the book. Attention to Ferry at this point may prevent Christians from the failure of love that is the misrepresentation of those with whom they disagree.

Similarly, Ferry’s critique of materialism is trenchant and convincing, noting “our logical incapacity to put aside the notion ... that there is within us something in excess of nature or history”.

His personal investment in the project is what makes the book so engaging, but ultimately for the Christian reader, so bittersweet.

Ferry wraps up the whole book with the assertion that “amongst the available doctrines of salvation, nothing can compete with Christianity ...”. Though he does not believe it, he is attracted to Christian faith, confessing, “were it to be true I would certainly be a taker”.

It took 263 pages to get to this truth question. Ferry, like so many, does not seriously consider Christianity’s truth claims; he simply does not believe.

This is a pity, not least because Christianity also has the capacity to address Ferry’s argument that a good philosophy should enable us to live in and for the present.

Christian theology actually doesn’t do what he accuses religions of doing - robbing us of the present through nostalgia on the one hand and excessive hope on the other.

Rather, in Christ the past is dealt with by the cross and future hope inaugurated by faith becomes the basis for redeemed living now. By reconciling past, present and future, Christian faith offers the only way to what Ferry calls “the only life available to us”, his definition of the good life - a life lived fully in the present.

Mark Stirling. This article was published with permission of Solas magazine.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o