How is it possible to conceive that intelligent people could worship Osho as a god? Because, like Sheela, by worshiping him they were serving themselves.

The story now explained in the Netflix documentary series explains the dark side of New Age.

The story now explained in the Netflix documentary series explains the dark side of New Age.

Creating paradise on earth can become a nightmare. Anybody who has been in contact with Eastern meditation practices has heard of Osho. The cult founded in India by this guru—at the time known as Bhagwan Rajneesh—terrorized America during the 80s. The story, now popularized by the documentary series Wild Wild Country, shows the darkest side of New Age spirituality.

Since Netflix released it, I haven’t stopped hearing about it but in superlatives. I’ve been interested in cults throughout my whole life. I grew up hearing my father explaining about the differences between one cult and another the same way others talk about football or politics.

To me, talking about cults is as normal as talking about music, cinema or books. I don’t need to check Internet websites to talk about Bhagwan. I still have many books on this guru on my bookshelves, published in the 80s and 90s. It had been a while since I had read about him…

In the 90s I became president of an association called Libertad (“Freedom”). This was one of the first organizations, back in the 80s, that had submitted a report on cults to the Spanish government. The issue was still topical in the media, albeit without the paranoia of the 80s; but it was still rare the week nobody talked about them in an article or TV program

The concern about cults not only evaporated with the turn of the century, but the whole perspective on it changed considerably. The focus of interest is not Bhagwan as a “guru of free sex” or Osho’s particular meditation technique anymore. The approach of a series as Wild Wild Country is much smarter than the exposés we were used to back then. Here we get to know the “human factor” that we Christians forget so often when we condemn everything as the Devil’s work.

Beyond the worship of money are the real idols we pursue.

Beyond the worship of money are the real idols we pursue.THE POWER OF RELIGION

Behind the search for a religion of power capable of transforming the world many times there’s only the thirst for power religion can give. That’s why saying that cults are nothing but a way of making money at the expense of others is tremendously simplistic. Money for what? That’s the question. Beyond the worship of that god everybody recognizes—money—lay the idols that truly move our hearts, like power, pleasure and fame.

The true main character in Wild Wild Country, Sheela, is not interested in money, but in the power her position as Bhagwan’s secretary and spokesperson confers.

Most people are unaware of the fact that who truly calls the shots in a cult is not its founder and prophet, be it Russell for the Jehovah’s Witnesses or Joseph Smith for the Mormons, but their lieutenants; the so-called judge Rutherford in the Watchtower and Brigham Young in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, to give a classic example from the 19th century. This also happens in Protestant denominations, by the way. They receive somebody’s name, who’s given them their theology and ecclesiology, but it really is someone else who shapes them and gives them their main idiosyncrasies.

In the world of cults, as in many churches, nothing is what it seems. Both secular sensationalism and Christian demonization fail at helping to understand cult members—if we truly have an interest in people. Sociological, psychological and criminal approaches deal with interesting aspects, but these are not essential to understand cultish phenomena. The question is not restricted to why someone becomes a member of a cult, but why they are happy with being one.

Many people are not aware that who really run cults are the second on board.

Many people are not aware that who really run cults are the second on board. THE MYTH OF THE GURU IN THE WEST

Even though the series starts with some data about Bhagwan in India, what is truly interesting is the experiment in Oregon—not the trouble he ran into before, nor his last days in Poona.

Born in a small Indian town in 1931 in a Jainist family, he rebels against his parents’ religion and goes into studying philosophy at the university, where he teaches until 1966. Then he becomes a guru after an “enlightenment” experience. He leaves because of problems with tax authorities, but this is only brought to light by a journalist later in the series. What’s really interesting here is how Sheela takes Laxmi’s place as his secretary.

Although Sheela was born in India, she leaves for the USA at 18. She studies at Montclair State University and marries an American. When they move back to India, they both become Bhagwan’s disciples, i.e. “sannyasins”, members of the community—or “ashram”—where they go into retreat to learn and meditate according to the teachings of their teacher, who lives under the same roof with them.

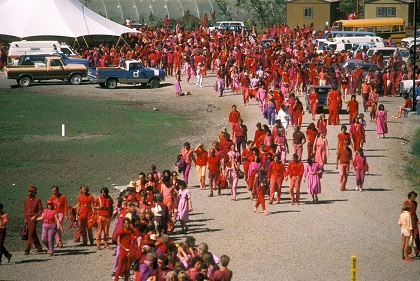

From the time Bhagwan opens his center in Poona in 1974 he starts attracting many westerners. It’s there, in India, where the press starts calling him “the guru of sex”. Many of his acolytes keep a hippie appearance into the 80s—in which the series takes place.

As Peter Washington shows in his classic book on the history of gurus in the West, Madame Blavatsky's Baboon: A History [...], even though the roots of this phenomenon can be found in the theosophy of the 19th century—which brings Krishnamurti to Europe—it’s not until the Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago in 1893 that the first gurus set up in the United States—mainly in California, where there already was a tradition of alternative communities.

A cult like this would have never had that kind of freedom in Europe: as the deputy of the state’s general attorney says in the series, if Bhagwan hadn’t sued Sheela before the authorities, the FBI would have never been able to enter the ranch. That’s the way religious freedom works in the United States.

SURPRISING SERIES

Many enthusiastic fans of this series are surprised by the fact that they didn’t know anything about this, even if they lived in the 80s in the United States. A great part of the success of this series is due to how little known these events that took place in Oregon are, in a cult as paranoid as Scientology, as controlled as Manson’s, and as criminal as Jim Jones’. To avoid spoiling the story for future viewers I won’t tell the events that the Way brothers tell us so brilliantly.

Not only did the directors interview all the characters who took place in those events that still lived, but they also achieve an intimacy that is rarely found in interviews typical of documentaries. When they find Sheela in the Swiss town of Maisprach, they travel there twice to get to know her, spending time with her. When they go back to do the interview, a year later, they record around four hours a day. Although she’s not as potty-mouthed as in her youth, she still keeps some of that cheek that has turned her into a sort of feminist anti-heroine, far from the naiveté prevailing in Eastern meditation circles in which people only talk about peace and love.

The production is skilled, having plenty of material thanks to the cheap medium video offered in the 80s—in the 70s, filming in 16mm was scarce due to its cost—coming from the news in local channels, but also from the recordings in Super 8 the cult took for proselytism purposes. All this with the accompaniment of Christian musicians such as Bill Fay and Damien Jurado, and also Bill Callahan’s wonderful bass voice; the series is named after one of his songs.

Another of the great things Wild Wild Country does, in my opinion, is that it avoids the dramatizations that cause so much damage to historical documentaries, as is the case with National Geographic’s. Those bad performances undermine the credibility of the story and turn it into a cheap show; in our case in point, illustrations are presented tastefully.

The most surprising thing is the objective tone that is used to relate the events; events very loaded with emotional tension and obvious prejudices. The best-known criticism to this was published in The Atlantic, written by a contributor whose mother left her family to join the cult. Obviously, this person’s viewing, constantly waiting to see if her mother will appear on-screen, has a very different value than the comments coming from so many who now discover these events. The novelty in this series, as well as in the series made recently about the Waco events of 1993, is that there is a new critical perspective also on the paranoia of the neighbors and authorities, who resorted to dubious actions in their harassment of the cult, such as voter suppression tactics.

The authors of the documentary believe followers of the cult were free adults who wanted a better life.

The authors of the documentary believe followers of the cult were free adults who wanted a better life.BRAINWASHING?

After American soldiers taken hostage during the Korean War went back home in the 50s, they told about the methods their captors used to try to win them for their cause. This is how the “brainwashing” theory was born, and also is, probably, the most popular explanation for why many former cult members speak well of them. Is it a sort of Stockholm syndrome (the psychological reaction that receives this name after observing how hostages talked in favor of their attackers in a bank robbery in Sweden in the 70s)?

The naiveté many Westerners show when signing up for therapy or exercises based on Eastern meditation and yoga, without thinking about their possible psychological effects—beyond relaxation—explains how many find themselves enslaved, emotionally dependent on their guru or leader, barely realizing it.

It is true that Osho’s therapy was unusual. Acolytes danced with wild abandon to then-current rhythms and had cathartic emotional explosions of shouting, laughing and crying. Not only were they naked part of the time, but they also practiced free love as if in a hippie commune. You can imagine the contrast with the few older neighbors living in the town of Antelope, where there was only one Episcopal Methodist church.

The neighbor who seems more likeable is the one who got to be mayor, John Silvertooth. His smile and the ease with which he can talk about this subject, without the gravity of the mayor who was in charge before the council fell in the hands of the cult, is as surprising as his final comments, when he says the ranch currently is a Christian camp owned by the Evangelical organization Young Life. “It’s kind of like a cult, too”, says the mayor. “We went from free sex, the Rajneshees, to no sex, Young Life”—he says jocularly. “They’re not perfect, but they are much better neighbors than the Rajneeshes.” It is at this point one realizes this is the objective perspective the directors are looking for.

The community they set up on this lost ranch, in a rural desert area in the center of Oregon only known for being where the founder of Nike is from, is not only dedicated to the search of “enlightenment” through meditation, dance and free love. They also work in agriculture, take in homeless people and help former inmates in their rehabilitation.

Not everything is black and white. As Sheela herself says, “Rajneeshpuram—the name they gave the town—is a great live opera. Operas always end in tragedy. But there were many aspects, many dimensions to this opera.”

THE DARK SIDE

“There is darkness in all of us”, says Bhagwan’s former lawyer, Philip Toelkes. After four years talking to Sheela, the directors say they never heard her saying anything reflecting remorse for the atrocities she had committed. She justifies everything. “This is a person with no empathy”, they say. It’s religion without compassion. Fanaticism wakes up hatred, because it can’t put itself in other people’s shoes.

Thus, beyond the search for personal self-fulfillment, we simply find the selfish dream of those who seek their own pleasure. This is the reason why children lived apart, and why everybody was sterilized or had vasectomies—something the series doesn’t mention—not only to be able to practice free love more freely, but because there wasn’t room for families within the cult. The cult was family. The accusations of children mistreatment—which the documentary also omits—are, to some people’s eyes, as serious as the poisoning of their neighbors.

When the directors are asked how can they explain that so many former acolytes have fond memories of the cult… maybe because they were “brainwashed”? Their answer is no, categorically. They don’t think they were “brainwashed”. Their impression is that “they were adults who joined this movement out of their own will to improve their lives.” What happens is “that absolute devotion can be manipulated and used against its followers.” That is, according to them, the experience of Australian Jane Stork (Shanti Bhadra), who “joins them with the best of intentions, to build a community based on love, harmony and peace, but ends up doing horrific things.”

One of Rajneesh’s followers in the 70s was the daughter of Congressman Leo Ryan, who was assassinated in Guyana by the followers of the Peoples Temple in 1978, while he was on his way to investigate Jim Jones’ cult. Shannon traveled to India to offer the money from his father’s life insurance to Bhagwan. Afterwards he moved to the community in Oregon, where she once said: “It is impossible that Bhagwan would ever ask people to kill anyone. But if he asked me to do it, I don’t know. I love and trust him very much. To me he is God. He sees more clearly than I do. But if I want to say no to Bhagwan, I’ll say no.” We people are that naïve!

The Ausatralian Jane Stork joins the cult with good intentions, but ends up commiting atrocities.

The Ausatralian Jane Stork joins the cult with good intentions, but ends up commiting atrocities. THE OLD NEW AGE DECEPTION

Osho teaches “Nobody is a sinner”, since “even while you are in the darkest hole of your life you are still divine. You cannot lose your divinity, there is no way to lose it. It is your very being.”

This is the ancient Serpent’s old lie, telling us we can be like God (Genesis 3). For Bhagwan, “there is no need for any salvation”, because “it is inside you.”

“I have to live with myself”, Sheela says at the end of the docuseries. “And this living with myself, I have to look inside me. Who am I? What am I? Why am I? There is no good and evil, right and wrong, black and white. Of course, I don’t know when I die if I’ll go to Hell or Heaven. But it doesn’t matter. Wherever I go, I will create my own paradise.”

She believes, like Osho, that “disobedience is not sin, but part of growing”. You are the measure of all things. There is no justice we will have to answer to ultimately. In trying to discern good from evil on our own, we become like God. One of the great paradoxes of idolatry is, as Romans 1 says, that the moment we stop recognizing the Creator, we start serving the creature.

How is it possible to conceive that intelligent people could worship Osho as a god? Because, like Sheela, by worshiping him they were serving themselves. The deification of the creature is nothing else than a way of deifying oneself. Since God is everything, according to Osho, and human beings are nothing but illusory forms of the divinity, there is no crime, no sin, no…

Evil, however, is a reality (Romans 3:23, 6:23). We can’t escape it. It is not unconsciousness, as Osho claims. To him, morality was a game that changed from one society at a given time to the other. It didn’t depend upon an ultimate reality. This is Satan’s old deception. Only by believing in Jesus can we be free of its unavoidable consequences (John 3:18).

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o