Fighting self-deception and corruption.

Illustration courtesy Marc Rosenthal (www.marc-rosenthal.com)

Illustration courtesy Marc Rosenthal (www.marc-rosenthal.com)

How much integrity do you have? If you are like most people, your response is a definite ‘lots!’

Yet in spite of our character strengths such as courage and loyalty, our self-appraisals of integrity can be seriously influenced by our own self-serving distortions—namely, rationalizing away inconsistencies between our purported values and our actual actions.

‘I am a moral person and a model person’ can be one of the greatest self-evident truths of human history, at least to ourselves.[1]

In this article we distill some of the lessons we have learned over the past 15 years in promoting integrity and confronting corruption. Why is it hard to live up to our moral and ethical aspirations?

We reflect on the reality of dysfunction and deviance, highlight the challenge of self-deception, describe anti-corruption resources, and summon the church-mission community (CMC) to a global integrity movement marked by righteousness and relevance.

We are the light—or the darkness—of the world

Integrity is moral wholeness—living consistently in moral wholeness. Its opposite is corruption: the distortion, perversion, and deterioration of moral goodness, resulting in the exploitation of people and planet.[3]

Global integrity is moral wholeness at all levels in our world—from the individual to the institutional to the international and everything in-between. Living in global integrity is essential for sharing the good news and good works among all peoples.

M. C. Escher, Circle Limit IV.

M. C. Escher, Circle Limit IV.It is also requisite for fostering sustainable development-transformation, health-wellbeing, and peace-security in our world. Integrity is not easy, it is not always black and white, and it can be risky.[4]

Searching for integrity

About 10 years ago I (Kelly) was in conversation with one of my closest friends, lamenting why it can be so hard for good people simply to try to do good in an organizational context. Why can organizational life, especially in Christian organizations, sometimes be so bleak? Why can integrity be so elusive?

An hour into this discussion of leadership hubris, systemic dysfunction, and wrongful dismissals, my friend gently offered me two words of advice: ‘Read Machiavelli’.

Manipulating virtue and vice

He was referring to the sixteenth-century treatise on power by Nicolò Machiavelli, The Prince.[5] Machiavelli resolved to develop a reasoned argument for leadership that was practical and reality-based, and not simply idealistic or solely virtue-centered. Power could be ‘legitimately’ unencumbered by ethical values.

So I read and reread Machiavelli, determined to upgrade my understanding of how the organizational world often works. Especially illuminating was a core principle from Chapter 15:

A man who wishes to act entirely up to his professions of virtue soon meets with what destroys him among so much that is evil. Hence it is necessary for a prince wishing to hold his own to know how to do wrong, and to make use of it or not according to necessity.[6]

Machiavelli’s work was a major influence in the realpolitik thinking that has impacted governance practices for the last five centuries, which has crept into the CMC, and which has undermined the global integrity so desperately needed in our world today.[7]

Exposing dysfunction and deviance

Unfortunately we can all be seriously duped and disabled by Machiavellian-type people and processes (Luke 16:8). We call these DD Realities (DD): personal and organizational dysfunction (distortion of reality for one’s own ends) and deviance (exploitation of others for one’s own ends).[8]

DD is often disguised as ‘virtuous’ or ‘necessary for the greater good’. In organizations, managing DD is especially tricky when there is insufficient understanding, accountability, or political will to enforce good practice standards resolutely.

Above all, DD is reinforced when people compromise their integrity by looking the other way, rationalizing their responsibility, and ultimately becoming polluted themselves (see Prov 16:2 and 25:26).[9]

Tactics for sustaining DD

This grid helps recognize the presence and progression of DD in organizational settings. These five tactics can overlap. The grid can also be used as a mirror into one’s own integrity:[10]

- Deny. Conceal DD. ‘Don’t ask about problems (even obvious ones), don’t tell about problems, and don’t rock the boat’ is a pervasive, core, unwritten rule.

- Downplay. Minimize DD’s negative impact. State that it is probably ‘normal’. Relational unity and conformity trump truth and genuine relationships.

- Distract. Distract from the real DD issues. ‘Feign pain’ and get sympathy; or admit that something is ‘not exactly right’ and refer to problems as being largely a matter of having different perspectives/preferences–a need to agree to disagree.

- Discredit. Belittle those who point out or inquire about DD. Silence them. Instill an atmosphere of fear of reprisals and intimidation to prevent people from speaking up or calling for good practice.

- Destroy. Demolish people’s reputations, contributions, relationships, and wellbeing. Use half-truths, spin, lies, rumors, threats, false accusations, and dismissals. Reap the benefits of control, position, respect, status quo, and revenue streams.

Practicing self-deception[11]

Cognitive dissonance is a powerful concept from social psychology that can help us to understand our propensity to deceive ourselves while still believing we are living in integrity (Jer 17:9).

It refers to the self-serving rationales that we use to calm our disturbing, internal incongruence and harmonize discrepant thoughts about ourselves—who we want to be versus who we actually are.

Tavris and Aronson (2007) shed light on how our inner moral maneuvers help us feel good about ourselves:[12]

Most people, when directly confronted by evidence that they are wrong, do not change their point of view or course of action but justify it even more tenaciously. Even irrefutable evidence is rarely enough to pierce the mental armor of self-justification….Yet mindless self-justification, like quicksand, can draw us deeper into disaster.

It blocks our ability even to see our errors, let alone correct them. It distorts reality, keeping us from getting all the information we need and assessing issues clearly. It prolongs and widens rifts between lovers, friends, and nations.

It keeps us from letting go of unhealthy habits. It permits the guilty to avoid taking responsibility for their deeds. (pp. 2, 9-10)

Bad leaders are bad news

Self-justification to minimize cognitive dissonance is a big reason why any leader can become a ‘bad’ leader—Machiavellian.

One international survey assessing the experiences/views of Christian leaders identified three main categories of negative characteristics of fellow leaders: ‘Prideful, always right, and always the big boss; lack of integrity, untrustworthy; harsh, uncaring, refused to listen, critical’.[13]

Robert Sternberg’s extensive research consistently finds that bad leaders see themselves as being above accountability—‘ethics are for other people’. They do not avail themselves of needed input from others to complement, balance, and correct themselves.

They lapse into an unrealistic and often disguised sense of omnipotence, inerrancy, unrealistic optimism, and invulnerability. They become entrenched in their ways, even when it is obvious to others that they are digging a bigger pit of mistakes into which they and others will fall.[14]

Tactics for feigning integrity

These four tactics illustrate what not to do when we are asked to give an account for a possible mistake or misconduct. Use this as a mirror into your own life and integrity:

- Distance yourself from the issue. Dodge, reword, or repackage it. Obfuscate the facts, talk tentatively or vaguely about concerns or ‘mistakes in the past’. Disguise any culpability.

- Appeal to your ‘integrity’ and acting with the ‘highest standards’. Point out your past track record, your current contributions, and that you are doing your best. Punctuate it all with the language of transparency and accountability without demonstrating either.

- State that you are being attacked, being treated unfairly, and that people do not understand. Remind everyone that leadership is hard and full of ambiguities and tough choices. Mention other peoples’ problems; question their motives and credibility.

- Hold out until the uncomfortable stuff goes away. Sack staff but do not change the system. Maintain your lifestyle, affiliations, and illusions of moral congruity. Remember, you are special. Cognitive dissonance applies to others but not to you.

Multi-sectoral resources for confronting corruption

Corruption is commonly defined as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.[15] It especially preys on the poor, with estimates of over one trillion dollars being siphoned off each year from developing countries.[16]

Within the CMC, an estimated USD 63 billion are stolen through ‘ecclesiastical crime’. This figure is more than the estimated USD 56 billion of income for ‘global foreign missions’![17]

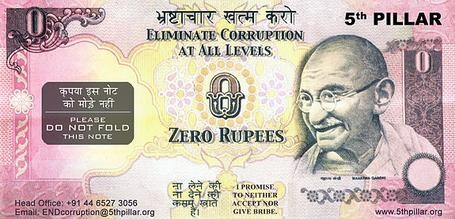

The Zero Rupees banknote, part of a major anti-corruption campaign in India.

The Zero Rupees banknote, part of a major anti-corruption campaign in India.Corruption is not just about financial fraud.[19] It also manifests as ‘bribery, law-breaking without dealing with the consequences in a fair manner, unfairly amending election processes and results, and covering mistakes or silencing whistleblowers (those who expose corruption in hope that justice would be served).’[20]

In the humanitarian sector corruption extends into ‘nepotism/cronyism, sexual exploitation and abuse, coercion and intimidation of humanitarian staff or aid recipients for personal, social or political gain, manipulation of assessments, targeting and registration to favor particular groups, and diversion of assistance to non-target groups.’[21]

A life of integrity

Fortunately, many publicized scandals and campaigns have sensitized us to the grim realities of corruption.[22] To combat corruption, we urge colleagues to:

a) cultivate a life of integrity: ‘Your task is to be true, not popular’ (Luke 6:26, The Message);[23]

b) appreciate your own vulnerability to temptation, including propensities to distort and justify mistakes and misdeeds (Prov 20:6); and

c) connect and contribute across sectors as people of integrity, keeping current with multi-sectoral resources on integrity and corruption such as those listed/linked at the end of the article and in the endnotes.[24]

Summons: A global integrity movement

Our globalized world is marked by extraordinary progress alongside unacceptable—and unsustainable—levels of want, fear, discrimination, exploitation, injustice and environmental folly at all levels….We have the know-how and the means to address these challenges, but we need urgent leadership and joint action now….I urge Governments and people everywhere to fulfill their political and moral responsibilities. This is my call to dignity, and we must respond with all our vision and strength (excerpts from Paragraphs 11, 13, 25). UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (2014)[25]

We believe our common identity and shared responsibility as Christians who are global citizens can be leveraged to integrate integrity into the individual-institutional-international levels, and everything in-between.[26] We believe it is a propitious season to invest in global integrity.

Gazing into the global mirror, contemplating our global integrity. Image source unknown.

Gazing into the global mirror, contemplating our global integrity. Image source unknown.We envision a growing, sustainable Global Integrity Movement, perhaps catalyzed by the Lausanne Movement[27] in collaboration with other major groups. It would be a platform for ‘connecting influencers, integrity, and ideas for global mission’.[28]

We call upon righteous and relevant people, committed to Jesus Christ and the good news, to work together resolutely and across sectors on behalf of the wellbeing of all people and the planet.

Global integrity requires ongoing, honest reflection at all levels. Like the character and virtue in which it is embedded, it is refined in the caldron of life’s tough challenges and choices. We are the light—or the darkness—of the world. We can be keys to influencing moral wholeness for a whole world.[30]

Kelly and Michèle O’Donnell are consulting psychologists based in Geneva with Member Care Associates (MCA). They focus their work on staff wellbeing and effectiveness, good practice and ethics, global mental health and sustainable development, and unreached peoples. Kelly and Michèle are representatives at the United Nations for the World Federation for Mental Health. Their resources and recent publications are listed on the MCA website.

This article originally appeared in the March 2018 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis and is published here with permission as part of the LGA Media Partnership. Learn more about this flagship publication from the Lausanne Movement at Lausanne.org/lga

Resources

Church-Mission Community

—Globethics (online resources)

—The Name of God is Mercy (2016), Pope Francis (chapter seven: ‘Sinners Yes, Corrupt No’)

—Thirty Pieces of Silver: An Exploration of Corruption in the Christian Scriptures (2014) Paula Gooder, Bible Society UK

—Salt and Light: Christians’ Role in Combating Corruption (2010) Paul Batchelor and Steve Osei-Mensah, Lausanne Global Conversation

—Corruption-Free Churches Are Possible: Experiences, Values, Solutions. (2010), Christof Stückelberger, Globethics

Corporate Sector

—Fraud Magazine (online resources)

—Toolkit for Business Leaders on Ethical and Transparent Business Practice (2014), EXPOSED Campaign

—Transparency: How Leaders Create a Culture of Candor (2008), Warren Bennis et al.

—Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths Go to Work (2006), Paul Babiak and Robert Hare

—UN Global Compact (2002/2004), (Principle 10, anti-corruption for businesses)

Humanitarian Sector

–Collective Resolution to Enhance Accountability and Transparency in Emergencies: Synthesis Report (2017), Transparency International

—Corruption: A Challenge that Does Not Escape the Humanitarian Sector (2016), Malika Aït-Mohamed Parent

–Fighting Fraud and Corruption in the Humanitarian and Global Development Sector (2016), Oliver May

—Humanitarian Accountability Report (2015), CHS Alliance (chapter nine on corruption)

—Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability (2014) and Guidance Notes and Indicators (2015), CHS Alliance (Principle 9)

United Nations

—UN Office on Drugs and Crime (online resources)

—International Anti-Corruption Day (9 December)

—Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015), (Goal 16 highlights corruption)

—UN Competency Development: A Practical Guide (2010), (rating and developing integrity, pp. 12-18)

—Convention Against Corruption (2005), United Nations

Various (government and civil society)

—Transparency International (online resources, including the new Anti-Corruption Knowledge Hub)

—Global Declaration Against Corruption (2016); Anti-Corruption Summit, London

—Corruption Perception Index (2016), Transparency International

—Moral Disengagement: How People Do Harm and Live with Themselves (2016), Albert Bandura

—Curtailing Corruption: People Power for Accountability and Justice (2014), Shaazka Beyerle

Videos

—Why Can’t Grace Go to School (2014), EXPOSED Campaign (three minutes)

—The Dangers of Willful Blindness (2013), Margaret Heffernan, TedTalk (15 minutes)

—Courage or Cowardice (2013), Mukesh Kapila, TedxTalk (14 minutes)

—Time to Wake Up (2012), Transparency International (one minute)

—The Psychology of Evil: How Good People Become Evil (2008), Phil Zimbardo, TedTalk (23 minutes)

—Confronting Idols—with Humility, Integrity, and Simplicity (2010), Chris Wright, Lausanne Movement (23 minutes)

Endnotes

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o