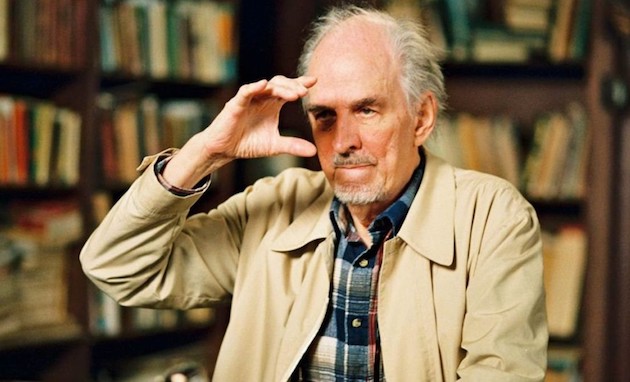

Ingmar Bergman (1918–2007) staged people unable to love and communicate, condemned to always hide behind a mask.

Bergman communicates about the solitude and the tragedy of the contemporary man.

Bergman communicates about the solitude and the tragedy of the contemporary man.

A hundred years ago, in Sweden, the son of a Lutheran pastor was born. His work in cinema and theatre would show us the solitude and tragedy of contemporary man, facing the emptiness of God’s silence. Ingmar Bergman (1918–2007) staged people unable to love and communicate, condemned to always hide behind a mask.

Borrowing from the title of a film about his parents, Bergman was a “Sunday’s child”, born on such a day in the summer of 1918, to a family of pastors that could trace itself back to the sixteenth century. His great-great grandfather was a pastor and he married a pastor’s daughter, as did Ingmar’s father.

Erik Bergman started off as the chaplain of a small mining community but then went on to preach at one of the most important Lutheran churches in Stockholm. Despite his nervousness and recurring insomnia, any weakness in Erik disappeared when he got up onto that pulpit. His unemotional and authoritarian character however created tension in his family, which ended up distancing Ingmar, who did not reconcile with him until shortly before his death.

The great-great grandfather of Ingmar Bergman was a pastor and married the daughter of a pastor, as his father did as well.

The great-great grandfather of Ingmar Bergman was a pastor and married the daughter of a pastor, as his father did as well.One Sunday, the Queen of Sweden heard Erik Bergman give one of his eloquent and lyrical sermons and offered him the chaplaincy of the Royal Hospital. From that point on, death became a part of daily life for Ingmar, who would see patient’s corpses as they went by. His best memories were of summer days cycling with his father to churches in the countryside surrounding Stockholm.

He found his father’s sermons boring but they gave him such an education that he once said that his films could not be understood without having read Luther’s Small Catechism.

THE BLACKEST OF PLAGUES

Bergman conceived a passion for cinema when he was a teenager. To start with his favourite films featured monsters, The Mommy or Frankenstein, although he also liked opera and classical music. He wasn’t much interested in politics, although in 1934 he went to Germany on an exchange with the son of another pastor who used Hitler’s Mein Kampf in his sermons.

With that family he attended a rally in Weimar, to hear the Führer and see one of Wagner’s operas. He was somewhat influenced by the Nazi propaganda, but his father realised the threat of Nazism and gave a famous sermon against them. In 1977, Ingmar recalled all this in “The Serpernt’s Egg”.

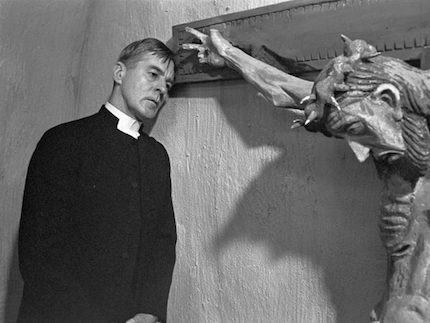

The Pastor of Bergman's films face the silence of God in the cross.

The Pastor of Bergman's films face the silence of God in the cross.Bergman always felt attracted to theatre. In the 1940s he began to direct plays with students, in particular plays by Strindberg, his favourite playwright, which were a permanent feature throughout his career. His first wife was a choreographer and his second, with whom he had four children, was a dancer.

Bergman became a film director in 1945, but he continued to work in theatre thanks to his constant frenetic activity. By his third marriage, with a historian and journalist, he already had five children. He didn’t smoke and he hardly drank alcohol. Life, for him, held some short bursts of happiness, but was in general defined by loneliness and the threat of impending death, making him eventually lose his faith in God.

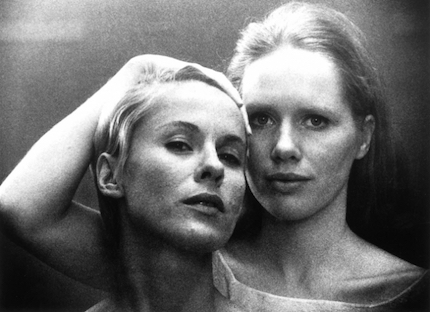

The huge female presence in his stories reflected his belief that happiness depended on a sexual harmony that he never found. In an interview that he gave a Swedish television channel when he turned 85, he said: “I have become a very nervous person with a propensity to cry… I am also very depressive”. There were days when he said that he spoke to no one. He lived alone and after four divorces and being widowed, he said that “love is the blackest of plagues”.

The big femenine presence in Bergman's film has to do with the sexual harmony that he linked to happiness, which he was not able to find in real life.

The big femenine presence in Bergman's film has to do with the sexual harmony that he linked to happiness, which he was not able to find in real life.

THE SILENCE OF GOD

The knight in The Seventh Seal (1957), perhaps his most famous film, is a tenacious and tortured seeker, who wants to believe. His shield-bearer is somewhat cynical and incredulous, although also compassionate. Like a revisited Don Quijote and Sancho Panza of Miguel Cervantes, they face Death itself, horrendous, devious and relentless…

DEATH: You want guarantees?

KNIGHT: Call it whatever you like. Is it so cruelly inconceivable to grasp God with the senses? Why should He hide himself in a mist of half-spoken promises and unseen miracles?

(DEATH doesn't answer.)

KNIGHT: How can we have faith in those who believe when we can't have faith in ourselves? What is going to happen to those of us who want to believe but aren't able to? And what is to become of those who neither want to nor are capable of believing?

(The KNIGHT stops and waits for a reply, but no one speaks or answers him. There is complete silence.)

KNIGHT: Why can't I kill God within me? Why does He live on in this painful and humiliating way even though I curse Him and want to tear Him out of my heart? Why, in spite of everything, is He a baffling reality that I can't shake off? Do you hear me?

DEATH: Yes, I hear you.

KNIGHT: I want knowledge, not faith, not suppositions, but knowledge. I want God to stretch out His hand towards me, reveal Himself and speak to me.

DEATH: But He remains silent.

KNIGHT: I call out to Him in the dark but no one seems to be there.

DEATH: Perhaps no one is there.

KNIGHT: Then life is an outrageous horror. No one can live in the face of death, knowing that all is nothingness.

DEATH: Most people never reflect about either death or the futility of life.

SEARCHING FOR THE ETERNAL FATHER

Bergman’s obsession with his father followed him until the end of his life. When he was at University, the two of them had an argument in which his father hit him. He hit back violently and threw his father to the ground. Despite his mother’s efforts to mediate, Ingmar left home and cut all ties with his father until he was dying in hospital. Then, at last, he tried to reconcile with him. Although he had already stopped working in cinema, he wrote scripts and made a few films for television, all related with his family problems.

Death appears in our life as the knight in The Seventh Seal.

Death appears in our life as the knight in The Seventh Seal.In it all one gets a tremendous feeling of bereavement, which personally brings me to tears. In his last interviews, Bergman said that people liked his films because, emotionally-speaking, he was a child and he spoke to the audience as a child.

The tragedy of his life reflects the reality of man without God. His silence is the end of all hope of finding love and meaning in this world. Bergman faced the reality of death alone…

I hope that that old man was able to finally meet that heavenly Father, who wants to receive us, when we go to him empty and broken. I realise that there is no greater privilege than the love that the Father has given us by making us children of God (1 John 3:1).

Do not let your hearts be troubled, Jesus says (John 14:1–2). He has gone to prepare the table for us when we get home. The fire of his eternal home is waiting for us when we believe in him. But nothing will compare to the warmth of the embrace of our loving Father.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o